Is Rick Perry Cheerleading for a Nuclear Trans-Texas Corridor?

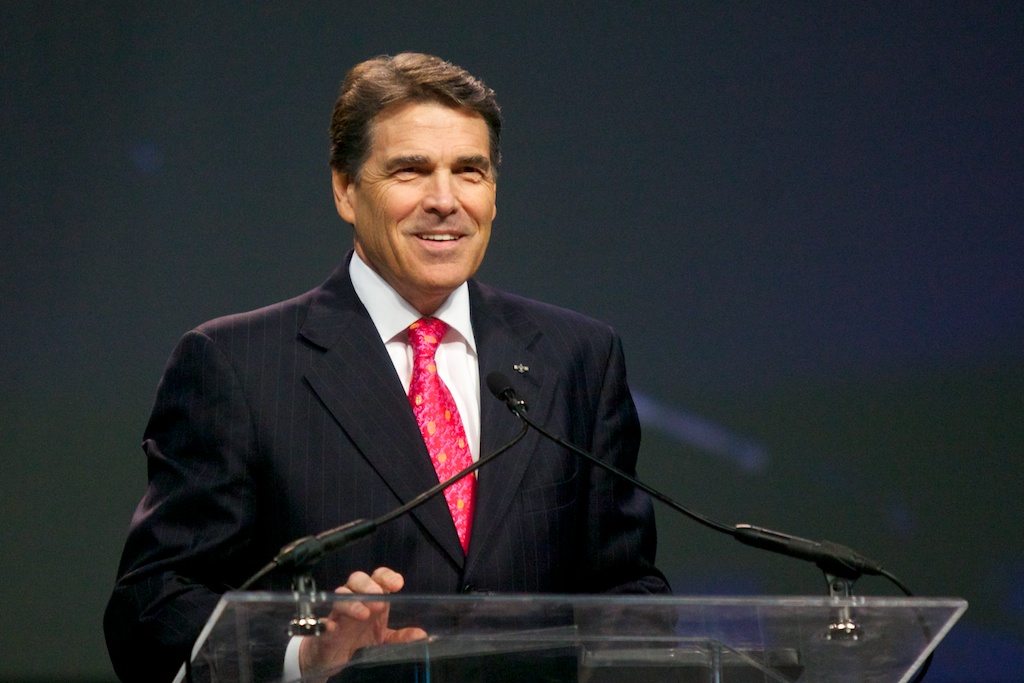

Above: Texas Gov. Rick Perry's prayer rally, The Response, at Reliant Stadium in Houston.

The companies angling to build a facility for high-level nuclear waste in Texas have found a high-level cheerleader: Rick Perry. This week the governor sent a letter to Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst and speaker of the House Joe Straus, urging the Legislature “to develop a Texas solution for the long-term resolution of [high-level waste] currently residing inside our borders.”

Perry’s boosterish letter follows Straus’ January directive to a House committee to study storage and disposal options for high-level nuclear waste.

The use of the phrase “Texas solution” in Perry’s letter is interesting. Go to texassolution.com and you will find a slick site for Waste Control Specialists, the radioactive waste company developed by the late Harold Simmons. Waste Control’s Andrews County dump was predicated on the notion that it would only take low-level radioactive waste, but just this week, the company began accepting—for temporary storage—transuranic waste from New Mexico’s Waste Isolation Pilot Project following a radiation leak at that facility.

In February, I asked Waste Control spokesman Chuck McDonald if the company was considering high-level waste.

“It is something we are open to the possibility of,” McDonald said. “We would obviously have conversations with the community in Andrews. … There is a new recognition that something may need to be done and interim storage may be something where we can provide a solution for the state and others if it comes to that. It’s very early in this process.”

Perry doesn’t mention Waste Control specifically and, indeed, there are other interests floating proposals for storing high-level waste in West Texas. Austin-based AFCI Texas, for example, has been sniffing around Big Spring for a while. AFCI is co-owned by a Perry crony—Bill Jones, who the governor appointed to serve on the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department board.

Officials in Loving County, which is the smallest county by population in the nation, have also expressed interest in hosting spent nuclear fuel.

Perry told a West Texas TV station yesterday that he believes there is a “legitimate site in West Texas.”

“Sure. I think there are a couple of sites in the State of Texas that the local communities actively are pursuing that possibility,” Perry told KCBD during a stop in Lubbock.

Along with his letter, Perry included a 49-page report drafted by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which lays out the options for storing high-level nuclear waste in Texas. Currently, the spent nuclear fuel from the nation’s 100 or so nuclear reactors has no permanent home. The federal government’s preferred option—burying the waste deep underground in the Nevadan desert at Yucca Mountain—has been more or less scuttled. In January 2012, a blue ribbon commission (are all commissions adorned with blue ribbons?) appointed by Obama recommended that work begin in earnest to develop one or more centralized storage facilities along with one or more deep geologic burial sites. The idea is that the waste would be shipped from the nuclear reactors to be stored temporarily for decades, until (or if) it could then be buried somewhere.

The report takes quite a bit of editorial license and seems to be particularly concerned with how to make a public-private storage option work. “The lack of an alternative to onsite indefinite storage is hindering nuclear energy from being fairly considered as an energy option and is an embarrassment to this country’s reputation for its capability to handle its waste.

Basically, the report suggests that the U.S. Department of Energy should own a centralized storage facility in Texas, where the spent fuel from nuclear power plants can be sent and held for decades, while it works on a deep geological disposal site. A private company, the report recommends, could operate the facility. The reason for the public-private arrangement is that the federal government would have title to the waste in case something goes wrong. Otherwise, building such a facility “may be too uncertain for a private company to attempt.” And we wouldn’t want that.

The authors stress the importance of finding a community that embraces radioactive waste, specifically citing the Waste Isolation Pilot Project in New Mexico and Waste Control’s dump in Andrews. “Finding a site that has local and state support would greatly enhance the chance of a private centralized interim storage site being successfully sited and constructed,” the report concludes.

The legal, political and technical hurdles involved in establishing even an interim storage site, much less a Yucca Mountain-style disposal site, are obviously significant. Just for starters, Congress would have to change the law to allow for the arrangement TCEQ/Perry is proposing. There’s also the teensy issue of transportation. Moving all the nuclear waste to a single central storage unit would take 20 years and up to 10,700 shipments by rail or 53,000 by truck. The radioactive waste would inevitably pass through thousands of communities, many of which might not like the idea of serving as corridor for a private company to profit from nuclear waste.

To my mind there are echoes of Rick Perry’s other splashy proposals: Think Trans-Texas Corridor or the mandatory HPV vaccine mandates—cronyism posing as bold public policy. Notably, both Trans-Texas Corridor and the HPV mandate were high-profile flops that nearly cost him his political career. Perry is not known as a Big Idea man or a policy wonk, despite his recent makeover with those MSNBC glasses and his appearance at Davos. Merits aside, his policy proposals have typically been the product of close allies and business interests pushing an agenda and using Perry as a pitchman. And they’ve not been popular with the conservative grassroots.

Perry’s executive order requiring Texas girls to get vaccinated for HPV caused an uproar on the religious right, who thought the state should have no business inoculating girls against a sexually-transmitted disease. Others were repelled by the crony capitalism angle: Perry’s former chief of staff, Mike Toomey, was a lobbyist for Merck, the company that sold the HPV vaccine Gardasil. Perry was forced to scrap the mandate and it haunted him when he ran for president in 2011-2012.

The Trans-Texas Corridor had something for everyone to hate: Rural Texans took exception to the use of eminent domain to seize land for a private company; environmentalists loathed the notion of building a vast new fossil fuel-driven infrastructure; and tea party types (before they were called that) saw the making of a vast intercontinental conspiracy at the heart of the Corridor.

It’s not clear whether there is a larger plan to the high-level waste deal, or this is just the governor’s usual business cheerleading. But the extensive TCEQ report, commissioned by Perry, suggests that there is some long-term effort at work. The question is whether the conservative grassroots takes any interest in the issue. There is not an obvious bugaboo as with Trans-Texas corridor or the HPV vaccine.

If the private interests can lock down local support perhaps any widespread opposition can be blunted from the get-go.