Review: James K. Galbraith Separates Fact from Fairy Tale in Bill White’s America’s Fiscal Constitution

I opened this book with a bad attitude. It would be, I felt sure, a Sermon from the Mount of Serious People, as pompous as those Peter G. Peterson used to inflict on readers of The New York Review of Books. The jacket endorsements deepened my fear; Bill Clinton, James A. Baker III and Ross Perot are not the sort who base blurbs on merit. Oh, and there was Erskine Bowles, who never saw a Social Security benefit he didn’t want to cut.

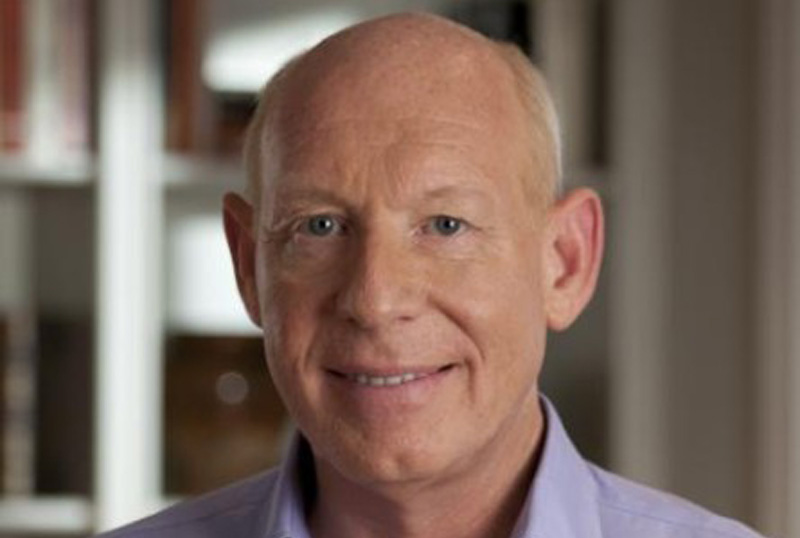

Former Houston Mayor Bill White’s book is the history of an idea. It is an idea with deep roots and continuity, one that continues to drive our budget discourse, and one that informs how most Americans think about deficits and debt. The idea is “fiscal responsibility.” As a topic of history, it is damn dry. And yet America’s Fiscal Constitution: Its Triumph and Collapse manages to tell its story vividly and well.

Is there an American Fiscal Tradition? White contends that since “Washington’s inauguration, the federal government has added debt only for four identified purposes.” These were 1) to preserve the Union; 2) to fight a war; 3) to secure and extend the borders; and 4) to fund deficits during a recession. More than a mere tradition, these principles, White says, are part of the country’s “unwritten constitution.” Or rather they were, until the catastrophic arrivals of the 21st century and George W. Bush.

White does a fine job of delving into the antebellum era, presenting Madison and Jefferson, Van Buren and Jackson—and a host of lesser figures—through the lens of the public debt. He weaves in references to the Hamiltonian “Report on Manufactures” and even one to the influence of British economist David Ricardo and his plan “to retire [British Napoleonic War] debt by purchasing it at market value—an almost 50 percent discount from face value—with funds provided by an immense, one-time tax on national wealth.” Shades of Thomas Piketty!

Then came the Civil War, paper money, inflation and more debt. White casts Sen. John Sherman, brother of Union Gen. William T., as the hero of postwar debt reduction, whose work culminated in 1879 with the adoption of the gold standard. In words no doubt meant to resonate today, White writes, “Debt reduction, not debt-financed stimulus, lowered interest rates and freed savings for private investment” [italics mine]. However, in the next paragraph he concedes that “Not all Americans experienced the benefits of this growth.” The moral commitment to the American Fiscal Tradition went right along with the immoral inequalities of the Gilded Age.

World War I meant still more debt, and the task of reducing it fell to another “fiscal hero”: Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon. White writes that “Mellon’s solid performance eventually won over most skeptics,” who found that he was “neither an ideologue nor a dilettante.” Perhaps not, but among skeptics not won over was Herbert Hoover, who made note in his memoir of Mellon’s advice after the crash of 1929: “liquidate… liquidate… liquidate.” (FDR’s IRS eventually charged that Mellon’s fiscal heroism didn’t extend to personal compliance with income tax—shades of Timothy Geithner!)

White’s thesis of an unbroken tradition requires that even the New Deal must have been an exercise in fiscal probity, rather than the vast economic experiment, including bond-financed investment expenditure, that it actually was. For evidence of sound financial intentions, White has to rely mainly on Budget Director Lewis Douglas’ 1933 “economy drive” and FDR’s disastrous decision, soon reversed, to balance the budget in 1937. Most historians treat the former as a feint and the latter as a mistake.

By Bill Whilte

Public Affairs

576 pages; $35

Fitting John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier into White’s fiscal tradition requires another stretch. The New Economics of that era was the avowedly Keynesian tax-cut stimulus program finally enacted in 1964. White quotes from JFK’s 1962 Yale commencement speech, correctly regarded as his premier economic statement, but he is careful not to convey any important part of what the president said. He notably does not quote: “Borrowing can lead to over-extension and collapse—but it can also lead to expansion and strength. There is no single, simple slogan in this field that we can trust.” Since the entire theme of White’s book is that there are such slogans, that quote might have caused a problem.

For vivid detail—White’s strongest suit—the best part of his book deals with the 1980s and after, with the Reagan Revolution and the struggles of Congress, George H.W. Bush and Clinton to bring deficits back down. But here again he pulls a punch. White wants the Fiscal Tradition to encompass even Reagan himself, and so we must believe that Reagan and his people regretted the deficits they produced.

This is unlikely. Budget Director David Stockman might have cared, but many others did not. In the early Reagan years, concern with the deficit came well after tax cuts, military spending, and even stimulus, which was thinly disguised as “supply-side economics.” That Reaganite insouciance opened political spaces that centrist Democrats have occupied ever since—right through the Age of Rubin—while tax-cutting Republicans became fiscal rogues. Deficit doves, myself included, have sometimes found themselves on the outs with respectable opinion in our own party, and even, on this point, allied with the rogues.

For White, the collapse of fiscal probity occurs not under FDR, JFK, LBJ or even Reagan, and not under Bill Clinton, the president whose credit bubble yielded our last balanced budgets. White’s villain—no surprise—is George W. Bush, with his tax cuts, global war on terror, and unfunded Iraq War, followed by the economic crisis, the Obama stimulus, and the ongoing stalemate over budgets and taxes. All prefigure, White believes, a massive rise in debt payments and interest rates, a crowding-out of private investment, and a long, dreadful decline unless sacrifices are made and America’s unwritten fiscal constitution is restored.

Here we pass from history into economics. And also from sense to nonsense. For while White has written an engaging narrative of political belief, actual history is not a morality tale.

For almost the entire history of the Republic, public and especially foreign debts had to be settled, ultimately, mostly in gold, which meant that borrowing was a burden. In the late 19th century, the need to borrow was obviated by a trade surplus. And until well into the 1960s we continued to live (in part) on the gold hoard built up during two World Wars. That was, for presidents and economists, a source of worry. But the situation changed in 1971, when Richard Nixon cut the link between the dollar and gold. The world ever since has been quite different—but exactly how remains, for many people, poorly understood.

The 1970s saw the dollar decline, but beginning in 1979, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker and high interest rates put an end to that. Since the early 1980s, the dollar—unbacked by gold or anything else—has been the world’s most widely held reserve asset.

This remarkable arrangement has seen the central banks of the great exporting powers accumulate vast stores of U.S. Treasury bonds and bills—basically bank accounts on which they never draw. In exchange, they send fabulous quantities of real goods, materials and services to be consumed in the U.S. This dynamic has become a foundation of our living standard, and a debt that we service, without inflation, at the world’s lowest interest rates. To create that debt—liability on our books, but desired assets to everyone else—as a matter of economics and accounting we must, most of the time, run a deficit here at home.

The “dollar standard” is not something the United States entirely controls. It stems in part from the world’s geography of oil, and in part from other people’s actions, including the growth of advanced industries in Japan and Korea and a vast expansion of consumer manufacturing in China. Why these countries ship us goods for money—never demanding goods in return—is for them to explain. They may change, but so far they haven’t. And so long as they don’t, a U.S. trade deficit, and hence, usually, a budget deficit, are consequences we cannot escape.

Immorality did not kill the American Fiscal Tradition. Bush didn’t kill it. Globalization and the God Almighty Dollar did.