Rahim AlHaj, Iraqi Oud Virtuoso, on How Music Crosses Cultures

AlHaj, who performs in Austin on Friday, is a former political prisoner whose music fuses Eastern and Western influences.

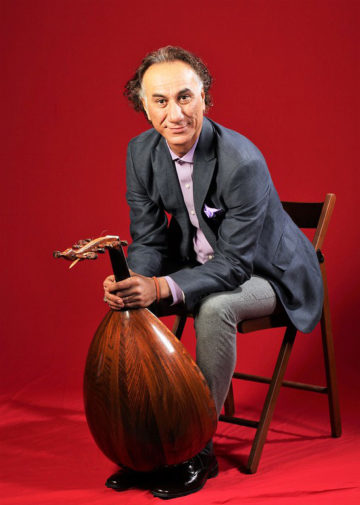

Above: “Even today, I say that my instrument is my breath. I cannot breathe without it.”

Rahim AlHaj’s music can seem bleak at first. His 2017 album, Letters From Iraq, is a mournful meditation on the violence wrought by the U.S. military invasion of his home country. So it comes as something of a surprise that this master of the oud—a pear-shaped Middle Eastern string instrument that inspired the invention of the guitar—is exuberantly funny, punctuating his sentences with a goofy cackle and exclamations such as “Oh, my God,” and “Can you believe it?”

Born in Baghdad in 1968, AlHaj was a musical prodigy renowned across Iraq by 13. He studied under the “king of oud,” Munir Bashir, at an elite conservatory. Music, however, wasn’t his only focus. Under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, AlHaj became an outspoken dissident. He spent two years as a political prisoner, enduring torture before fleeing to Syria, Jordan, and, in 2000, the United States.

The Office of Refugee Resettlement sent him to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where AlHaj found work as a dishwasher and security guard. He became convinced he’d never make it as a professional musician in the United States. So, about a year after his arrival in New Mexico, he decided to put on one last concert to raise money for a plane ticket back to the Middle East. “I felt hopeless, powerless,” he remembers. “No English. I had oud, a lot of art and books, and that was it.”

After the concert, AlHaj says, a little boy came backstage to ask for his autograph. He was so touched that he decided to stay in Albuquerque, which he still calls home. AlHaj has since toured with R.E.M. and the Kronos Quartet, released 12 albums, been nominated for two Grammys, and in 2015 was personally congratulated by President Barack Obama for winning a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. Ahead of his performance on Friday at Austin’s McCullough Theatre, he spoke with the Observer about his life and music.

Tell me about the oud. It’s one of the world’s oldest instruments, right?

The oud is about 5,000 years old, and it’s the most important instrument in the Arab world. I fell in love with it in second grade, when my Arabic teacher brought his oud to class. In Arabic schools, the teacher is like a god—it’s very formal—but I worked up the courage to ask him if I could touch the instrument. I remember vividly that I couldn’t sleep that night, I was so happy. Two days passed and my teacher brought it to class again. He let me play it that day, and as soon as I put my hand on the fingerboard, he freaked out and said, “Oh, my God, you are a musician.” And he started teaching me.

Did you know early on that this was wanted you wanted to do professionally?

I did. Though I don’t think a person really chooses to be a musician or an artist. It’s beyond that. You have to be obsessive about your art; otherwise you’ll give it up, because it’s too hard. As a child, I couldn’t sleep without my oud for about five years. I would talk to it and put it in my bed, cover it with a blanket. One night my father passed by my room and heard me saying to the oud, “I’m sorry, I’m exhausted, I can’t practice today, but I will tomorrow.” He went to my mom and told her, “Our son is insane. We need to do something about this.”

Even today, I say that my instrument is my breath. I cannot breathe without it.

The eight original compositions on your album Letters From Iraq are all based on real letters written by Iraqi citizens. How did this project come to be?

When I was visiting Iraq in 2015, my teenage nephew told me he wrote a letter to the United States. He brought his notebook and showed it to me, and I was in tears from this story. So then I start collecting more letters, stories written by Iraqi women and children, and at first I just did some lectures about it. But then I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great if I could translate these to music?” Now we’ve toured to Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Central Asia—everywhere.

I consider this work to be not just letters or music, but a historical document of a moment in time. My friends and family in Iraq, and everyone there, have been suffering from death and destruction for so long. They told me, ‘We hold no animosity against Americans, but we need them to listen to our story and to recognize that we suffered.” I’m trying to give an American audience a chance to open their hearts and minds and just listen.

Walk me through one of the letters and how you turned it into music.

The letter from my nephew is called “The Running Boy.” One day, a beautiful day in October in Baghdad, he went to have a haircut. He has a disability causing his leg to be bent so that he cannot walk straight. This day he walked to the barbershop and was waiting there. People were talking about a soccer game between Barcelona and Madrid, and he felt so happy, because he loves soccer and wants to chat about it too. All of the sudden, there’s a huge bombing near the barbershop, and everybody runs. Except he can’t run, so he’s standing there seeing dead people, fire, people crying. He collected his power to walk, and just then another car bombing happened. He said, “This is it, I’m dying. My mother and sisters and brothers all came to my head saying goodbye.” But he walked away, and he survived.

The song starts with very slow movement, as if he is talking about his difficulty in walking, and then when he describes the people chatting, the instruments talk together. Then you hear the bullets in a bip! bip! and the sound of ambulances and crying. I use the string quintet—cello, bass, oud, violin, and viola—because there’s so much variety of sound I can express, so much color I can add to the painting.

You became a U.S. citizen in 2008. What did that mean to you?

That’s a beautiful question. I always say that nationality is not a choice, but home is a choice. My wife bought me a world map and put it in my office, and whatever country I visit, she puts a pin in it. She counted them up, and I’ve been to at least 87 countries. Eighty-seven! I’ve lived in many beautiful places: Paris, Damascus, Baghdad. But New Mexico is my home.

It’s a dark time to be a refugee and an activist. What gives you hope?

I actually hate this word, “refugee.” I think it’s wrong, because nobody immigrates unless they have to. We’ve all been moving from one spot to another since humanity started.

From an early age, I’ve been obsessed with social justice and equality. It’s sad that after all these years of fighting and writing music, we are still so far away. But we cannot be defeated just because there’s somebody in charge who’s an idiot. So I’m still protesting, still resisting, making music.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Critical Condition: Rural health care is in crisis around the country, but Texas is suffering the most. At least 20 small-town hospitals have closed since 2013.

-

Governor Clears Out Camps. Austin’s Homeless Remain Homeless: Greg Abbott began clearing out the camps under Austin’s highways Monday, over the objections of the homeless and their advocates.

-

When ICE Emptied Out an All-Women Detention Center in Texas, Chaos Ensued: Women formerly detained in Karnes County Residential Center have been lost in the shuffle, facing moved or cancelled court dates, high bonds, and legal confusion.