Over the Wall

After a decade of living in the shadow of the border wall, people in the Rio Grande Valley are ready to move on. But Donald Trump has other plans.

“Well, OK, I’ll talk to you,” Eloisa Tamez told me. “But you’re the last reporter I’m ever going to speak with.” It was late March, and CNN, NPR, the BBC and countless other media outlets had converged on the Rio Grande Valley to report on the “big, beautiful wall” that President Trump had promised to build. Tamez was one of the first people they sought out. For years she had been a leader of the landowner resistance in South Texas, speaking out often and eloquently against the folly of a wall.

Her activism began in 2007, the year after Congress passed the Secure Fence Act, authorizing up to 700 miles of border fence. At the time, Border Patrol agents were going house to house in Cameron County, asking landowners to sign over their land. Tamez, then an associate professor in the graduate school of nursing at the University of Texas at Brownsville, politely told them to get the hell off her property. No way was she going to allow them to ram a wall through her 3 acres on the Rio Grande without a fight.

Tamez filed a lawsuit and prevented the government from taking her land for more than a year. But in 2009, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed her case and construction began on the wall.

In 2014, she finally settled with the government, reluctantly accepting $56,000 for a quarter-acre of her land occupied by the wall. By the time Trump supporters began chanting “Build the Wall,” most Americans had forgotten that the southern border already had 670 miles of fencing and barriers, including 110 miles in Texas.

But there hasn’t been a day that Tamez and other border residents are not reminded of it. One-third of the 320 condemnation suits filed against landowners in 2007 are still pending a decade later. In recent months the Trump administration sent out a new round of condemnation letters to landowners, in anticipation of Congress funding Trump’s proposal to build 34 miles of wall in the Valley.

By the time Trump supporters began chanting “Build the Wall,” most Americans had forgotten that the southern border already had 670 miles of fencing and barriers.

And so the reporters had come to South Texas. For months Tamez had demonstrated for the TV crews how she punches in a passcode to open a massive gate in the wall that lets her pass from one part of her land to the other. She explained how her land was once part of a 12,000-acre Spanish grant deeded to her ancestors by the king of Spain before the United States even existed. She posed in front of the wall looking defiant. It made for great TV. But now, like so many other border residents, Tamez just wanted to be left alone. She was tired of America’s fears and obsessions with its southern border. Tamez was suffering from border security fatigue.

++++

As I drove west from Brownsville toward Tamez’s home in the small community of El Calaboz, the hulking wall came into view, snaking through backyards past barbecue pits and swing sets. The wall couldn’t be built on the banks of the Rio Grande because a U.S.-Mexico treaty prohibits development in the flood plain. The river spills over its banks from time to time, and a fence could push floodwaters into communities on both sides. So, instead, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) erected some segments as far as a mile inland from the Rio Grande. The wall cuts through the center of the University of Texas-Rio Grande Valley and bisects neighborhoods and city parks. And some U.S. landowners live south of the barrier in a sort of no-man’s land.

Tamez greets me at the door of her modest home with a smile. She has a youthful energy and wears a colorful blouse that matches her turquoise and yellow reading glasses. At 82, Tamez still goes to work every day at the university. The walls of her living room are covered with framed black-and-white family photos. One of them shows her parents, young and smiling, tilling the soil to plant crops. In another photo, a young Tamez and her siblings gather around their mother under the shade of a mesquite tree, not far from where the wall stands today.

When the 5th Circuit declined to hear her appeal, Tamez said, it broke her heart. “My lawyer told me, ‘You can stop fighting. They’ve already taken the land,’” she said.

Afterward, Tamez used part of the $56,000 in compensation to create a scholarship fund for graduate nursing students. Tamez named the endowment after her parents. She also decided to offer her home as a basecamp for researchers examining the effects of militarization and the wall on border communities.

“People will sometimes come up to me at Sam’s or Walmart to congratulate me,” Tamez said. “Though I didn’t really win anything. I lost my land. But they think I won.” Tamez smiled wryly. “I don’t tell them anything different. I think it’s because they read about the scholarship fund in the newspaper. That’s what people remember. And I’m proud I’ve been able to turn something negative into something positive that is going to help our community.”

Tamez said she suspects the fight between landowners and the DHS will be even more protracted and bitter this time. The cheapest, most accessible places are already taken. At least 35 percent of the U.S.-Mexico border already has a barrier, mostly in New Mexico, Arizona and California. If Trump is to build hundreds of miles of new border wall, much of it will have to be along Texas’ 1,250-mile border with Mexico, including rugged terrain traversing Big Bend National Park and the vast expanses of Falcon Lake and Amistad Reservoir. At least 95 percent of the Texas border is privately owned.

It was Tamez who, in 2008, had first opened my eyes to a disturbing fact about the wall’s construction: It seemed to be bypassing the wealthy and the politically connected while targeting those who could least afford to fight the federal government in court. Tamez questioned why her land had been condemned while the Riverbend Resort, a gated community and golf course two miles down the road, had not. In 2008, my article “Holes in the Wall” showed how an army of subcontractors working for the Boeing Company, which had the multibillion dollar contract to oversee construction of the wall, appeared to be passing over properties owned by wealthy landowners in favor of land owned by working-class families.

Tamez says she sees some justice in the possibility of Trump’s wall being built on the property of the wealthy who avoided it last time.

“Go ahead and fill in the holes in the wall,” Tamez said. “Because those belong to the wealthy. We’ll see if they build it through the Riverbend Resort this time, but I doubt it.”

Tamez said she was recently invited to a congressional hearing on Trump’s wall, but turned down the invitation. “I’m not going to be part of that spectacle anymore,” she said.

She’d rather have lawmakers meet her on her own turf, she said, not in Washington, D.C., or as part of a carefully scripted tour with local elected officials and business leaders. “My story is a real story about what this barrier and these government policies have done to me as an ordinary citizen,” she said. “I want them to walk the land with me and understand. But they never come here.”

++++

After visiting with Tamez, I traveled 50 miles west to meet with Hidalgo County Judge Ramon Garcia in his expansive office near the courthouse in Edinburg. If Tamez and her neighbors in Cameron County took the most direct hit from Bush’s wall, it is Hidalgo County that is likely to be one of Trump’s first targets. When I talked to Garcia in March, he was in the midst of controversy. In February, he’d sent a letter to John Kelly, Trump’s Homeland Security secretary, inviting the administration to convert 28 miles of earthen flood levee along the Rio Grande into a concrete barrier topped with a steel fence. The structure, he argued, could do double duty as a border wall and river levee.

Garcia’s invitation outraged many of his constituents, who saw it as an unnecessary, or at least premature, capitulation to an administration that had disparaged the border, Latinos and immigrants.

He explained to me that his letter was merely pragmatic politics. The wall is inevitable, Garcia said, and the county should get the best deal it can. “I personally don’t see any way of stopping it,” he said. “If they want to do it, they’re going to do it.”

In 2008, then-County Judge J.D. Salinas had made a similar calculation, offering Homeland Security the then-novel idea of a 22-mile levee wall. At the time, DHS was planning to build an 18-foot fence north of the levee, which meant razing homes that stood in the way. But that was an expensive proposition, not to mention bad optics in the media, so DHS seized on Salinas’ idea. There was just one caveat: Hidalgo County — one of the poorest in the nation — would have to kick in $44 million toward construction. Though the county tapped its drainage improvement fund to pay for the levee wall, U.S. Senator John Cornyn, who had voted for the Secure Fence Act, assured Salinas and other county leaders he would get Congress to pay them back. But the bills Cornyn introduced to reimburse Hidalgo County never passed.

This time, Garcia offered to chip in $38 million, 10 percent of the proposed $380 million project, with the understanding that it would probably never be reimbursed. In his letter to DHS, Garcia helpfully included new plans drafted by Dannenbaum Engineering, the firm that made millions building the 22 miles of levee wall nearly a decade ago. (In late April, the FBI raided local government offices in the Laredo area as well as four Dannenbaum offices across Texas in an operation that the FBI has said very little about, to date.)

While Garcia sought middle ground with the Trump administration, other elected leaders were vocal about their hatred of the wall. One Democratic congressman from nearby Brownsville, Filemon Vela, made headlines last year with his open letter calling Trump a “racist” and telling him, “You can take your border wall and shove it up your ass.”

A month after our visit, Garcia and the Hidalgo County commissioners, under pressure from constituents, reversed course on the levee-wall idea altogether, writing another letter to DHS — this time emphasizing their opposition to any kind of wall.

One Democratic congressman from nearby Brownsville, Filemon Vela, made headlines last year with his open letter calling Trump a “racist” and telling him, “You can take your border wall and shove it up your ass.”

It may be too late. In its proposed budget, the White House asked Congress to fund the construction of 28 miles of “new levee wall barriers” in Hidalgo County. Though the stopgap budget that Congress passed in early May doesn’t contain funding for the levee wall, the idea is unlikely to go away.

++++

Garcia’s change of heart was in part the handiwork of Scott Nicol, a McAllen artist, teacher and activist. There is probably no one better versed in South Texas’ border walls than the 47-year-old Nicol. Over the last decade, he’s made a careful study of the Secure Fence Act, poring over contracts and submitting voluminous open records requests for government documents.

Shortly after Garcia sent his first letter capitulating to the Trump administration, Nicol wrote an op-ed in the McAllen newspaper, the Monitor, pointing out that if Congress were to fund the project, DHS would be digging up 28 miles of earthen levee that had just been repaired with $220 million in federal stimulus money.

In late March, Nicol, who is co-chair of the Sierra Club Borderlands Team, took me on a tour of the levee wall that was built in 2009, so I could see its effect on the local environment. “The whole project is just a huge waste of money, and devastating for the wildlife,” Nicol told me as I followed him along a gravel trail behind the Old Hidalgo Pumphouse. The pumphouse, which used to draw river water for farm fields, now houses a museum that anchors a nature preserve and several acres of wetlands connected to the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge. The refuge, in turn, is part of a riparian wildlife corridor that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has acquired piecemeal over the last 30 years at a cost of more than $70 million.

The 18-foot levee cuts through the wildlife corridor for 22 miles and seals off the river, a vital source of water, from wildlife stuck north of the wall. If the Trump administration builds another 28 miles of levee wall, the same would happen in the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge and Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park. In Nicol’s view, the wall would ruin much of what’s left of the Valley’s natural habitat. Even without the wall, conservationists were in a race against time.

Today, most of the Rio Grande Valley looks like Southern California with its traffic-choked expressways, strip malls and fast food restaurants. At least 95 percent of the native habitat has already been developed or farmed. And the wildlife corridor is increasingly vulnerable, especially with DHS’ “force multipliers” of surveillance cameras, Border Patrol vehicles and walls. This subtropical riparian sliver is one of the most biologically diverse areas left in the country. It’s the northernmost territory for the endangered jaguarundi, ocelot and other species.

In 2006, the Hidalgo pumphouse became part of the World Birding Center, an ambitious project to encourage birders and other nature lovers to visit the region. Every year, thousands of bird watchers come looking for buff-bellied hummingbirds and great kiskadees, species that can’t be seen anywhere else in North America. Economists at Texas A&M University estimate that birders generate more than $340 million a year for the regional economy. From Roma to South Padre Island, cities along the border collaborated to invest more than $60 million in observation areas, wetlands and native plant restoration to promote ecotourism. The state also invested at least $1 million in the effort. But in 2008, two years after the Hidalgo pumphouse reopened as a museum, DHS began construction on the levee wall just behind it, severing it from a 4-mile hike and bike trail through the wildlife corridor.

I followed Nicol a mile east of the museum to the end of the levee wall, where two Border Patrol SUVs idled, the agents waiting to nab anyone who might come across the river.

After Trump was elected president, Nicol started getting calls from reporters from all over the world on their way to the Rio Grande Valley to write about Trump’s wall. Nicol was one of the only people in the Valley who hadn’t grown tired of talking to the media yet. “The first thing you have to explain is that the Texas-Mexico border is a river,” he said. “And then you have to explain that the wall is not on the river.”

The agents in the SUVs looked away as we walked around the edge of the levee wall and down a dirt road heavily rutted by the Border Patrol vehicles that patrol between the wall and the Rio Grande, a half-mile away. Mesquite, ebony and wispy huisache trees dusted with yellow flowers formed a dense canopy. A javelina rooted through the underbrush, then fled as we walked south on the abandoned trail toward the river.

Nicol reminded me that there were surveillance cameras all around us, some owned by the state, some by the feds. There were also ground sensors. We were in the United States, on land managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, but it felt like we were trespassing. The terrain was beautiful but neglected. Trees had toppled onto the asphalt trail and we had to fight our way through vines and brush. Hiking through this forgotten zone, I had the sensation of America recoiling from the Rio Grande and taking shelter behind its wall.

We bushwhacked for nearly a mile until we came out again at the rutted dirt road. One of the Border Patrol SUVs came speeding toward us, trailing a white cloud of dust. Nicol stopped and I followed his lead as we waited for the vehicle to reach us. “We tripped a ground sensor,” Nicol said. He was used to these kinds of encounters. I was apprehensive.

The agent rolled down his window. “What are y’all doing out here?” he asked.

“Just hiking the trail,” Nicol said, nonchalantly.

The agent sized us up for a moment. “All right,” he finally said, nodding, then rolled the window up and sped away.

“I’m pretty sure DHS has a file on me,” Nicol said, smiling. “A really thick one.”

++++

No city in Hidalgo County has grown faster or become more economically prosperous than McAllen — largely due to its trade with Mexico. But the repeated border bashing from Washington has started to threaten McAllen’s hard-fought prosperity. I met up with Jim Darling, the mayor of McAllen, early one morning after he’d participated in a groundbreaking ceremony for a new shopping center. We had coffee at a recently opened Corner Bakery Cafe across from a brand-new Best Buy off Expressway 83.

Like Tamez, Mayor Darling said he was fed up with doing interviews about border security and the wall. The issue had become so polarized, Darling said, he wasn’t going to continue to lend his face to the media circus.

“It didn’t matter what side of the media I was talking to, they had a presumed message already. I got tired of it. We’re fighting this image that doesn’t depict who we really are,” he said, cradling a cup of coffee in his hand. “When we do surveys of the top 10 concerns for our residents, the No. 1 concern is traffic congestion, and security is like No. 8.”

For years, the city of McAllen — which has a population close to 140,000, “but more like 250,00 during the day,” Darling said, because of shoppers from Mexico — has had an economy that’s outpaced many other parts of the state. “We’re a poster child of NAFTA,” Darling said. Every year his city sends $200 million or more in sales tax to Austin, but gets little love in return. Instead, McAllen and other border communities are often used as a photo op for politicians talking tough on border security for their constituents back home. “Talking down on the border wins votes in Beaumont or Duluth,” Darling said.

Many Americans imagine the border as a desert, devoid of people other than human traffickers and drug smugglers — an image often reinforced by politicians: John McCain talking tough in a 2010 re-election ad with an Arizona sheriff as they strolled past a border fence and dusty vistas. McCain: “Complete the dang fence!” Sheriff: “It’ll work this time.”

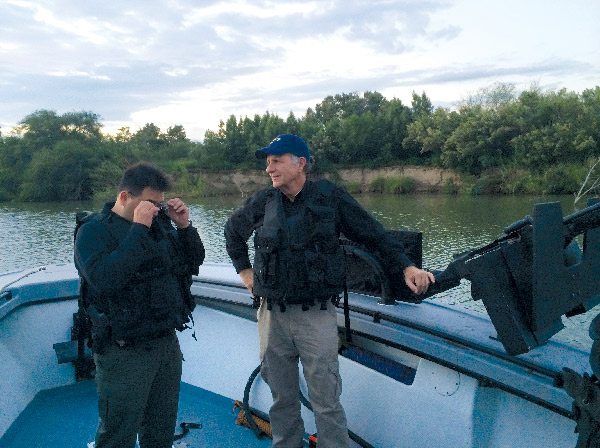

Or former Governor Rick Perry and Fox host Sean Hannity in 2014 looking tough for Fox viewers in backward baseball caps and wrap-around sunglasses on an armored DPS gun boat with enough horsepower to reach Veracruz by morning.

And then there’s Donald Trump, who in a July 2015 visit was accompanied by an oversized security entourage that tailed him around town as he congratulated himself on having the courage to come to “dangerous” Laredo.

Since Trump’s inauguration, a steady stream of congressional leaders has been visiting McAllen to get a look at “Ground Zero,” as Attorney General Jeff Sessions recently called the border, painting it as a hellscape rife with “filth” and head-chopping cartels. Paul Ryan, the speaker of the House, was still a topic of conversation among McAllen residents a month after his visit, because he’d opted for something a little different on his tour: hopping on a Border Patrol horse, which then bolted toward the river with panicked agents in pursuit. Afterward, Ryan tweeted a short video of himself on his mount, seemingly to prove he’d always been in control. Dozens of protesters had gathered along the street as his motorcade passed. Ryan didn’t stop.

Darling is so familiar with the border photo op that he is practically a connoisseur. “Typically, the Republicans like to ride on the river, and the Democrats go to the detention centers,” he said.

But the visitors often find it jarring when they learn that the lawless border they’ve heard so much about in Washington, D.C., is actually pretty pleasant.

There was the time in late February when Senator John Cornyn came down with Republican senators from Massachusetts, Wisconsin and Nevada for a ride-along with the Border Patrol on the river. They were standing on the dock in their life preservers, ready to get on the boat, when one of the senators noticed an amusement park full of children on the other side of the river.

“He asked what it was,” Darling said. “And I told him it’s an amusement park in Mexico. He started taking pictures of it. He was amazed.”

Another time, Darling was out on the Rio Grande with visiting dignitaries, all under the watch of heavily armed federal agents, when a party boat from Reynosa, Mexico, floated by. “They were dancing and drinking and waving,” Darling said, smiling. “It was pretty funny.”

Darling blamed the media for depicting his town as a crisis zone. Pushing back, I asked him about all the “war on the border” rhetoric coming out of Washington and Austin. What were visiting reporters supposed to think when they arrived at the park where politicians typically embarked on their river tours? As a reporter, I know the place well. It’s a county park with playgrounds and barbecue pits. But no one goes there anymore. Like the nature trails behind the Hidalgo pumphouse, it’s bristling with surveillance and a long line of DPS squad cars parked near the dock. Then there are the armored DPS boats outfitted with .30-caliber guns that wouldn’t look out of place in the Suez Canal. The park had become another border security sacrifice zone where no one ventured except for police and federal agents.

Darling listened politely, but said it was still the media’s fault. He especially blamed George Stephanopoulos, the former Democratic adviser and now anchor of America’s top morning TV show, Good Morning America. During the 2014 Central American migrant exodus, Stephanopoulos potrayed Darling ’s city as a place under siege. Darling found that hard to forgive.

“Stephanopoulos called it a crisis on the border,” Darling said. “But the crisis was in Central America, that’s why the families were leaving. The crisis wasn’t here. Mexican migration was at net zero when the Central Americans started coming in 2014,” he said. “And they were asking for asylum, so they weren’t technically illegal, and I think we handled it well.” (The city of McAllen and Hidalgo County spent more than $480,000 helping the families and were never reimbursed by the federal or state governments.)

“But now middle America believed the border was in crisis, and being overrun by Mexicans, and we needed a border wall to stop them,” Darling said. “And that’s how we got into this mess we’re in now.”

I brought up Darling’s recent letter to the DHS secretary, which, like Garcia’s letter, supported the idea of a levee wall. “No one likes a wall down here,” he said. “But building a wall was Trump’s defining moment during his campaign, so we figure he’s going to get it built no matter what.”

“But now middle America believed the border was in crisis, and being overrun by Mexicans, and we needed a border wall to stop them. And that’s how we got into this mess we’re in now.”

All of Trump’s negative rhetoric and the talk of building the wall and making Mexico pay for it had already damaged McAllen economically, he said. In the wealthy Mexican industrial city of Monterrey, 150 miles south of the border, “McAlleando” was popular slang for “shopping.” But now, Mexican shoppers already reeling from the devalued peso were encouraging their fellow consumers to boycott McAllen in a social media campaign called #AdiosMcAllen.

“We’ll probably be down $3 million-plus this year in sales tax revenue,” Darling said.

To stop the economic slide, the city is investing thousands of dollars in advertising to encourage Mexicans to come back to McAllen.

“We are friends,” Darling said. “And they are always welcome here.”

But what words could make up for a wall? With much of the southern border already behind a wall, only Texas remains. The Rio Grande Valley is first on Trump’s list.

Before I’d left Tamez, I asked if she had any advice for the next wave of landowners who will be targeted by DHS. “Ask questions,” she said. “And write every single detail down that they tell you. And think long and hard about what it will cost you in the long term, after they take your land away. I didn’t have much, but what they took from me no amount of money could have ever replaced.”

This article appears in the June 2017 issue of the Texas Observer. Read more from the issue or become a member now to see our reporting before it’s published online.