Proposed Fetal Tissue Rules Create ‘Staggering Financial Burden’ for Texans

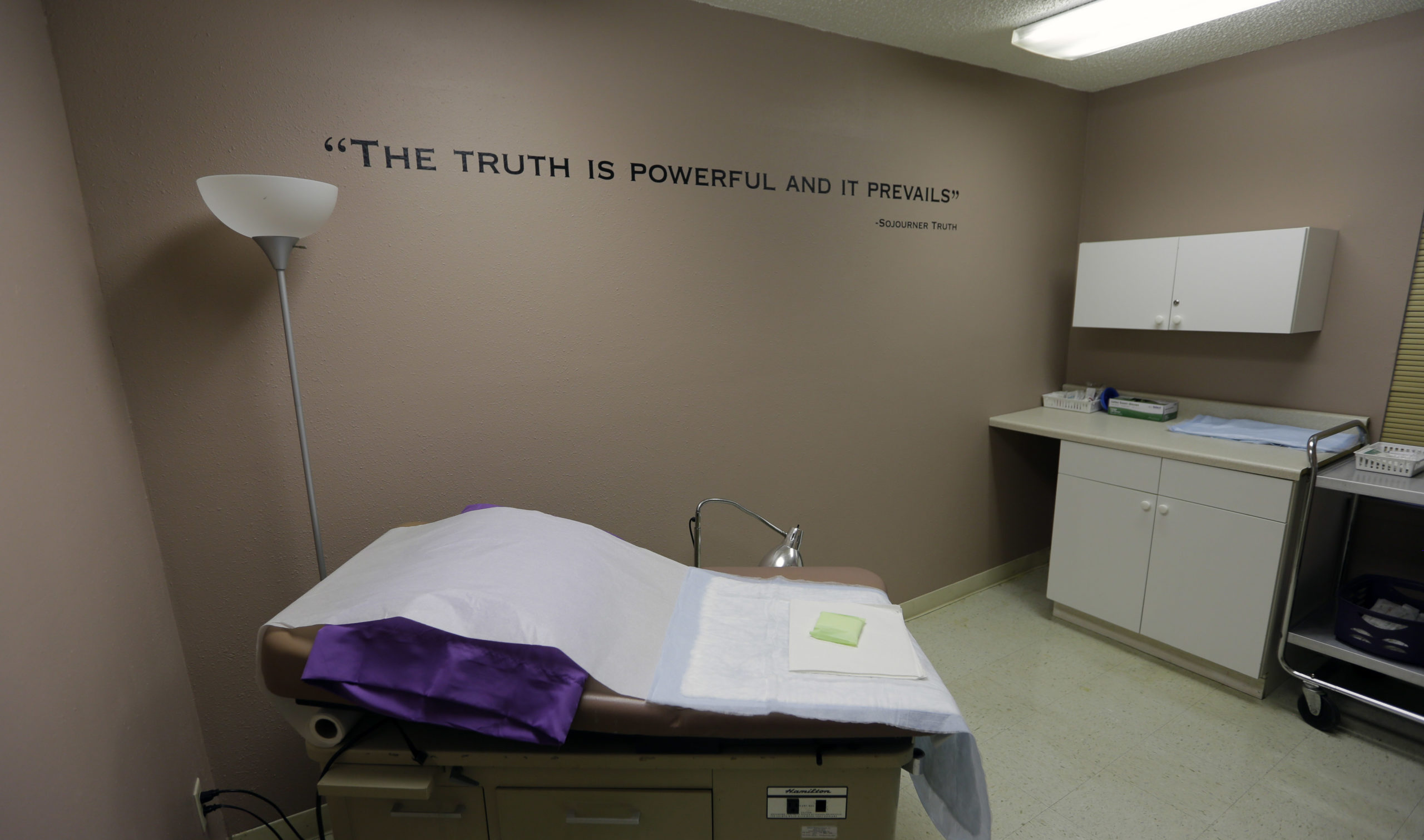

On July 1, 2016, the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) proposed new regulations that would require the cremation or burial of fetal tissue from both induced abortions and miscarriages – regardless of the period of gestation – that occur at health care-related facilities, including abortion clinics, ambulatory surgical centers, birthing centers and emergency rooms.

Normally, such facilities incinerate or dispose of human tissue by other approved methods. A hearing concerning the new requirements is set for Thursday in Austin.

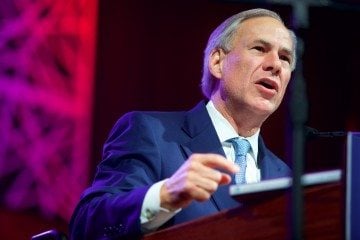

These new regulations solve no existing problem, create a host of pointless burdens not just for abortion providers or medical professionals but also for those in the funeral business, and they could cause the cost of ending a pregnancy to skyrocket for families. All of this not because current regulations pose a risk to public health, but because Governor Greg Abbott said so, along with state Representative Byron Cook (R-Corsicana). Cook wrote the agency on May 20 to express his dismay that fetal tissue did not have to receive the same disposition as human remains and to argue that the current regulations, therefore show no “respect for human life.” He learned the agency was already working to amend the regulations.

I’m not a doctor, but I do have expertise in writing and following government regulations as an attorney. I’ve researched abortion practices and studied the funeral industry for over two decades as a consumer advocate. A look at what these regulations would really mean in practice shows just how wrong-headed, convoluted and impractical they’d really be.

Some background about fetal development can clarify the significance of the proposed regulations, which would require a facility where the abortion or miscarriage occurs to carefully isolate fetal tissue for special disposition — “interment, cremation, incineration followed by interment, or steam disinfection followed by interment” — at its expense, or to turn the tissue over to the family or a funeral provider to arrange for one of the dispositions allowed by the proposed regulations.

At four weeks, a fertilized ovum — an embryo — is about the size of a poppy seed. At thirteen weeks, a fetus is 2 1/2 to 3 inches long — about the size of a small goldfish or pea pod, weighing less than one ounce, or about the weight of one slice of whole-grain bread. In the United States, between 89 percent and 92 percent of all induced abortions occur in the first trimester, up to that thirteen week mark.

In the new proposed regulations, published quietly before a holiday weekend in the Texas Register, the state health department does not explain how a 4-week-old embryo can be cremated, or even easily identified by medical personnel in the case of a spontaneous abortion — a miscarriage — that occurs at a regulated facility. Experts estimate that between 15 and 20 percent of those who know they are pregnant miscarry; among people who may not yet know they’re pregnant, that rate could be as high as between 60 and 70 percent.

If a patient begins to experience the symptoms of a miscarriage — bleeding, lower back or abdominal pain, cramping, etc. — she might seek evaluation from her physician, at a hospital emergency room, an abortion clinic, a birthing center, or at one of the now- ubiquitous outpatient clinics that treat minor emergencies. These proposed disposition rules would apply to all of these facilities except a doctor’s office.

The logistics of burying and the technologies of cremating embryonic or fetal tissue after abortion or miscarriage point to significant problems with the proposed regulations: There simply isn’t much to bury or cremate. That’s just how biology works. Let’s start with cremation.

Requiring the expenditure of any money to bury an embryo the size of a poppy seed strikes me as regulation beyond common sense or common decency.

A miscarriage is generally considered a pregnancy that is spontaneously aborted within the first 20 weeks. Even a 20-week fetus would leave an infinitesimal amount of residue after cremation, since cremated remains are mostly bone residue. Bones are mostly cartilage until about the seventh month of gestation, when they begin to harden or ossify. Before or in the very early stages of ossification, according to the Infant Cremation Commission of Scotland, “the cartilage or connective tissue prototype for the bone can be lost entirely in the cremation process as all the organic matter in the body is combusted.” Some fetal bones can be identified after cremation at 20 weeks, yielding a tiny amount of residue. Seldom is any residue found at 16 weeks or less of gestation.

Another report from the Scottish organization concludes that regular cremators are unlikely to yield recoverable remains from fetal cremation. The report suggests that special cremation practices and small-scale cremators could be developed that would yield recoverable residue from the cremation of some fetal remains. Perhaps the use of baby cremation pans (currently used for cremating infants) will help in recovering some residue from fetal cremations.

But DSHS doesn’t seem to have considered these issues in proposing its new regulations.

The burial of such remains would avoid most of these problems with the quantity and structure of the remains, but would still result in significant costs to families. Burial costs could range anywhere from $1,000 to several thousands of dollars, depending on how elaborate the services are that the family would select and where the burial would occur, with commercial cemeteries costing the most. Even the least expensive disposition options, direct cremation and immediate burial, both done without any ceremonies, will cost more than the $400 to $500 cost of a first-trimester abortion. Immediate burial will, at a minimum, cost nearly three times more than a first-trimester abortion procedure.

Requiring the expenditure of any money to bury an embryo the size of a poppy seed strikes me as regulation beyond common sense or common decency.

Burials carried out directly by the patient could avoid much of the costs involved with dealing with a licensed funeral establishment, if the family is able to manage that task. That still leaves the problem of securing the usual transport, burial or cremation authorizations or certificates, if they will be required — another factor not addressed by the proposed regulations. It should be expected that funeral homes, as regulated entities, will want to have some official documents as evidence of the services they have provided.

No one can know exactly what funeral costs will be, because funeral homes do not routinely arrange the cremation or burial of fetal tissue at thirteen weeks. If regular rates are charged, costs for direct cremation can be as low as $575 or as high as $3,040, and costs could be between $1,200 and $4,990 for immediate burial, according to the results of a 2016 funeral price survey published by the Funeral Consumers Alliance of Central Texas. These charges do not include any funeral or memorial services or ceremonies for the fetal tissue, additions that could double or triple the payments to funeral providers. The burial or entombment of cremated remains would entail additional significant costs.

If a funeral establishment performs the cremation or burial services, it will have to pick up the fetal remains wherever they are located, provide appropriate shelter for those remains, provide refrigeration after 24 hours, conduct an arrangements conference, coordinate the arrangements with others (ministers, cemeteries, crematories, newspapers, organists, etc.), and, if a full funeral or memorial service is chosen by the family, make staff available for the services, arrange for burial at a cemetery (opening and closing a grave site, providing equipment, etc.), and provide facilities for memorial services or funerals. Normally, funeral providers expect to be paid for all of these services.

The total costs to Texans of cremating or burying the remains produced by spontaneous miscarriages that occur in health-care facilities is nearly unthinkable.

It is not reasonable to expect that regulated health care facilities will be able to absorb the burial or cremation costs of induced abortions or miscarriages. In all likelihood, then, these facilities will have to turn over the fetal tissue to the patient for disposition in accord with the proposed regulations.

The state health department seems to have proposed regulations not out of need, or to serve valid public policy goals, but rather for two other reasons: To put financial pressure on facilities in Texas that provide induced abortion services, and to substitute political, religious, and personal views of public officials for decisions by Texas families about when life begins and what constitutes appropriate disposition of their fetal tissue.

The result is likely to be an enormous financial burden on families, who will be saddled with the costs associated with cremating or burying fetal remains. And it will be an unnecessary intrusion into the highly personal decisions of these families.

The department should withdraw these regulations until it has conducted public hearings around the state to receive the thoughts, ideas, and comments of all individuals and groups that will be affected by the proposals. It should consider the staggering financial burden on Texas families that these proposed regulations will likely create, and the denial of personal liberty in making disposition decisions after an abortion or miscarriage.