The Night Martin Luther King Jr. Came to Dallas

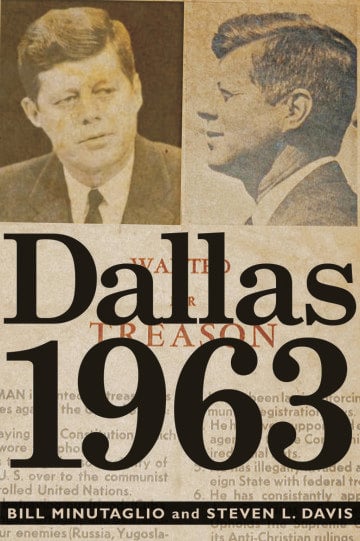

An excerpt from Dallas 1963.

A version of this story ran in the November 2013 issue.

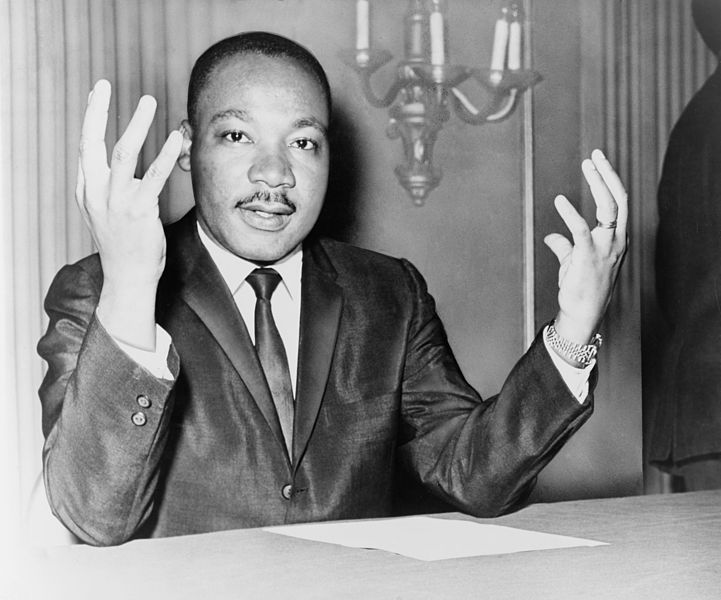

This month marks 50 years since John F. Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas. In their new book, Dallas 1963, Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis examine the city’s culture in the early 1960s and the events that led up to JFK’s death on Nov. 22. Then, as now, the far right wing of American politics was becoming increasingly paranoid and agitated. In the following excerpt, Minutaglio and Davis recount Martin Luther King Jr.’s little-known visit to Dallas in January 1963. The civil rights leader found a seething, segregated city that 11 months later would claim the president’s life.

This is the night Rhett James has been dreaming of for Dallas. He has finally succeeded in luring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. It is King’s first visit in seven years—the previous time had been a below-the-radar address to a church youth group—but now he will make a wide-open public speech at the big Music Hall at Fair Park. As the clock ticks past 7 p.m., James goes through his checklist and makes sure his church’s gospel choir is ready to provide the music.

There is an electricity, an almost palpable buzz—some people won’t be convinced until they actually see King set foot on a Dallas stage. Not everyone is happy, of course: Two hundred protesters huff and stomp outside, yelling that King is a communist.

James knows they are there, but maybe today can be a day of healing, a time for the hate to be put aside. Word is coming in that there are well over 2,500 people in the hall. Looking out, James can see some white people squeezing into the rows up front. James had made a point of inviting staunch conservatives, including the GOP chairman in Dallas—but they declined.

Suddenly, the panicky rumor blurts out: The police think there is a bomb in the building.

Fair Park is home to the largest assemblage of art deco public buildings in America. Built in 1936 to celebrate the centennial of the Republic of Texas, the park has been the scene of long-running battles to integrate the State Fair—it was there that Juanita Craft and her teenagers from the NAACP once stood outside, politely handing out literature, dutifully holding signs.

Now there is a bomb scare, and Craft is probably not surprised. She has been openly critical of Dr. King, though she certainly understands his motivations, and those of Rosa Parks, someone she considers a friend. Craft was a front-line warrior in the first unsuccessful attempts to get the State Fair and the Music Hall integrated—but lately she is worried about Dallas, and thinking that violence is in the air, and that blood may be spilled. Maybe it’s lunatic to invite King into a place like Dallas—where so many see King as the man unraveling the social order, as the very face of the liberal-socialist-communist insurgency in America.

The first story ann-ouncing King’s arrival hit the front page of the black newspapers a few weeks ago, while King goes virtually without any mention in The Dallas Morning News. He is the one black American the big daily newspaper is most wary of. Dallas has worked too hard, too long, to tamp down any hint of aggressive unrest in the city. The threat King poses is evident in the 20-minute movie the Dallas Citizens Council had paid for and screened a thousand times all across the city. Narrated by a forceful Walter Cronkite, Dallas at the Crossroads featured newspaper editors, ministers, prosecutors, police, and businessmen—all white, all cautioning that Dallas will implode if civic disturbances catch fire. One stern Dallas elder after another stares directly into the camera and speaks in grave tones about the consequences of Dallas acting irrationally:

“Nothing is gained by lawlessness,” one of Dealey’s editorial writers somberly says. “Violence, civil disorder, riots are crimes equally punishable under the law the police will devote their energies to controlling those few who do not have the judgment and character to obey the law: We know who those few are,” threatens Police Chief Jesse Curry.

“Dallas is a good city—and we want to keep it that way. Together, we shall show America ‘the Dallas Way,’” insists Mayor Earle Cabell.

Right now parents who had wanted their children to see the famous Dr. King are pulling their kids closer. James has to be afraid that this crowning moment, this civil rights flare shot straight from the heart of inflexible Dallas, will be utterly ruined. People can hear the chants from the protesters outside.

One of them, Jimmy Robinson, a 24-year-old from a Dallas suburb, is eagerly telling reporters: “We don’t want to start a commotion. We just want to let the people know that we do not believe in what the NAACP and Martin Luther King stand for.” He is representing the National States Rights Party, he says, a pro-segregationist group from Georgia whose founder describes Hitler as “too moderate.”

Inside the auditorium, James has to consider King’s safety, and what all this means for Dallas, and even for himself. He has been working for five straight years to bridge Dallas to the national civil rights movement, and this could be the culmination. He led some of the first wide-scale and organized civil rights protests downtown; he helped spur the integration of Dallas schools. He writes the most hard-charging column in the city, in the leading black newspaper; he leads a church founded by slaves; he serves as head of the NAACP; he is in regular communication with Lyndon Baines Johnson; and now, almost as a capstone, he has finally gotten King to come to Dallas.

He has told people King will address the poll tax. King and James are fighting it on all fronts, while still urging people to figure out how best to pay it so they can continue to vote. But many people are hoping for more. They want to hear King’s version of Dallas at the Crossroads—not the version from the people downtown. They want to hear how Dallas will change, and how fast it will change.

Maybe that’s why someone in the city might want to kill Martin Luther King Jr.—and everyone who has turned out to see him.

In that morning’s edition of the black newspaper, James wrote his regular column. He could have written about King’s upcoming visit that night. He could have written another one of his scorching indictments of corrupt politics, wretched poverty, or racism. But instead, he wrote about love. About how he hoped that Dallas, in 1963, would have the most peaceful, blessed year in its history:

“Live up to the best that is within you live each day as if it were your last day on earth rise above the trite experiences of life and elevate your life into a sphere of radiant and peaceful union with your inner self and your personal relationships may this year be your best year yet.”

There really are, James prayed, some signs that Dallas is changing. Maybe if people rise to their feet to cheer Dr. King it will be a sign that Dallas is not a city of hate. That Kennedy has a vision for America. That Johnson is squarely at a distance from the haunted traditions in Texas. That he and Kennedy symbolize a union—a joining of the old frontier with Kennedy’s New Frontier, a way to move the nation forward beyond its fractured past.

Maybe, in 1963, Dallas can finally move away from the anger, the bile, and the violence.

By 8 p.m. the police have finally determined that the bomb threat is probably, hopefully, just a hoax to drive King’s audience away.

The police teams still circulate inside and outside, keeping a wary eye on the roaming picketers. The police push them at least 25 feet away from the building, so the attendees can continue to enter in an orderly fashion.

From the front of the hall, James can see the leading rabbi in the city, someone who has been trying to lure Stanley Marcus to join his temple. He can also see the leading black attorneys in the city, the ones who are working directly with Thurgood Marshall to push for desegregation around the nation. There are other preachers and members of different congregations—he can see men from Carter Temple, Lone Star Baptist, Good Street Baptist, the Magnolia CME Church, and many, many more.

James finishes his prayers, the invocation, and the salutations and introduces the reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

The last time King was in Dallas he was just beginning his crusade, and he had come to speak to that group of young people at a local church. The Dallas teenagers probably had no idea what dangers he was facing, how things were racing toward confrontation and change around America. That was seven years ago. King would no doubt have come back to Dallas if he had been invited—but even many black leaders in the city were afraid of what his visit would unleash.

Staring at the filling auditorium, King is no doubt still thinking about the appropriate message to convey to a city like Dallas. Dallas is complex, with history layered upon history: There is that minister, R. E. Davis, who claims he leads the national wing of the KKK from his home, close to where Jack Ruby and Lee Harvey Oswald have lived; the Confederate cemetery is just a long walk away from the very podium where King is standing; the “stair-step” integration plan is a laughingstock in black activist circles around the nation.

King decides to focus his Dallas speech on “America’s Dream.”

“Segregation is the strange paradox of the principle that all men are created equal,” he begins, his voice ringing over the hushed audience.

Many people in the room have never heard King speak in person.

“We must get rid of the notion, once and for all, that there is a superior and an inferior race.”

Suddenly, some people are on their feet, interrupting him with rising applause. King pauses and then seems to echo what James has been searching for, pushing for, hoping for in Dallas since the moment he arrived in the city:

“We must develop a powerful action program to break down the barriers of segregation,” and we must be honest “with ourselves and our white brothers: Segregation is wrong. It is a new formula of slavery covered up with nice complexities.”

King nods toward politics, toward Kennedy: He has “done some impressive things in civil rights, especially when compared to the previous administration.” He talks about Kennedy wanting to open up the business portals, the bedrock things that are the special ken of the Dallas Citizens Council, to black people. To poor people. And says that Kennedy should not stop with any order he has handed down to advance equality in the workplace—in the boardrooms. The Kennedy mandate has to push harder, deeper, into the entrenched realms. The Kennedy blueprint is a start, and even if it scares some people in Dallas, the blueprint is not the end: “It does not do the full job,” shouts King. And President Kennedy “must give the order teeth if it is to work.” In the audience, people are clapping, raising their hands to the roof. Some shout out: “That’s right!” King soaks in the applause and decides, now that he has set the table, he can issue an advance warning—to Dallas, and to America. The movement is prepared to move things to another level, to push for a sweeping boycott of businesses. What has happened in Dallas and other cities, the de facto desegregation, is just a beginning. Any businessman in Dallas can be singled out by black citizens. White businessmen can become “targets of a nationwide ‘selective buying’ program.”

James has been shouting it, writing about it, and now King—the one so many people in Dallas thought was fomenting revolution around the nation—is at a podium inside the once perfectly segregated civic jewel of the city and telling black Dallasites to have the courage to storm the gates.

The crowd bursts into applause at least 25 times during King’s 45-minute plea for justice in America, in Dallas.

“If a man has not found something worth dying for, he isn’t fit to live,” King shouts, his words echoing to the back of the room.

For a second, he seems almost too harsh, too combative.

King decides to add one more thing: “One can struggle to end the reign of segregation but yet love the segregationist.”

And again, the couple of thousand faithful in Dallas roar their approval. King is waving his hands in the air:

“The Declaration of Independence does not say some men it does not say all white men it does not say all Gentiles it does not say all Protestants it says all men are created equal! If the American dream is to be a reality, the idea of white supremacy must come to an end now and ever more.”

By Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis

Twelve

384 pages

$28.00 Twelve

Sometimes, the nightmares come back in crystalline detail. A short, solid-looking man named Jack Oran, who now runs a small bicycle and motorcycle shop in Dallas, always remembers what happened to him in the concentration camps: He is pushing out of a bunk bed filled with six people. There is a dead man in the camp, someone whose pockets can be picked for scraps of moldy food. A piece of old bread, covered with lice, is on the floor and people are fighting for it.

And then he is being summoned, one painfully gaunt man among hundreds, to see Dr. Josef Mengele—the Nazi monster at the Auschwitz death camp. Oran is castrated. No anesthetics are used. He is sewn up, blood is running down his legs, and he is ordered back to work. He is certain his parents, his four sisters, and his brother have all been killed.

Now it is 18 years later, and he is 39 years old.

After the Russians opened the gates to Auschwitz, he found his way to the United States. He got a job as a dishwasher in the Jewish ghetto in New York City—and then followed the promise of jobs, and an American Dream, to Dallas. He met a woman and they adopted three children. He opened up his bike store—he was good at fixing things, working patiently on broken parts and putting them back together.

He has been reading the papers, following what General Walker has been saying, what Reverend Criswell has been preaching, what H.L. Hunt’s Life Line program has been airing, and what The Dallas Morning News has been printing. In the paper, just a few days ago, there was a man from a Dallas suburb named Jimmy Robinson, someone swearing allegiance to an organization founded by an American who thinks Hitler was too lenient. Robinson had come out to protest against a preacher, Dr. King, who is professing equality—and love—as an alternative.

Jack Oran has seen political extremism develop before. Although reticent to discuss his past, he decides that he should no longer be silent: That was the great failing in Europe—too many people were silent. He begins scheduling talks before local groups, to churches, to synagogues, to civic organizations, to veterans’ groups, to the Kiwanis and Rotary Clubs. He tells people how he came to have the death camp number 80629 scratched into his body and about how evil really does exist how hatred exists how it is allowed to fester and then it is fed by indulgence, by some sort of swelling fervor and hysteria. That is how it all begins—until all sense of humanity is ended.

He has been speaking in public for several months now, telling his story. Each time he talks he is flooded with the same emotions and nearly breaks down. Some people hug him, others are racked with tears. Some just bow their heads and pray.

Be aware. There is hatred, extremism, and it is feeding itself like a fire. It is the way it began with the Nazis. Please don’t let it come to Dallas.

It is Jan. 25, and it is near freezing, brutally cold. Oran is through with work, finally returning to his modest home. His neighbors like him; he is a dignified but friendly man. A few of them know his history, have seen his death camp tattoo. And a few realize that something is troubling him about Dallas, and making him feel obligated to do something he avoided for years. To talk in public, to address strangers, to warn people.

As Oran pulls onto this street, there is a strange, unnatural glow coming from the direction of his house. There are wisps of smoke and dancing embers blowing over the grass and sidewalk.

He stops and stares. Someone has jammed a giant wooden cross into his lawn and set it on fire. It is roaring, blazing, and people are coming out of their homes to see it, to gape at it. Oran is almost dizzy as he goes inside and calls the police.

It takes days, but Oran finally learns that the police have picked up a suspect. His name is Jimmy Robinson, the same man who was leading the angry protest against King’s visit to Dallas.

Oran learns that the man grew up in deep rural Texas and was drawn to Dallas only a few months earlier. Robinson defiantly, almost proudly, admits to the police that he set the large cross on fire at the Holocaust survivor’s house. He did it, he said, because he didn’t like what Oran was saying in his speeches. He pays a $10 fine and is released.

Excerpted from the book DALLAS 1963. Copyright © 2013 by Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis. Reprinted by permission of Twelve Books. All rights reserved.