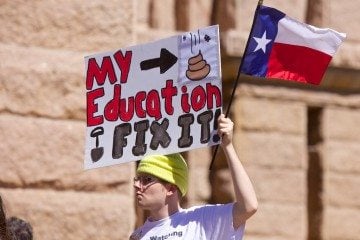

First School District Set to Join Parents’ Lawsuit Over STAAR

Struggling Marlin ISD says it’s ready to become ‘ground zero’ for standardized test reform.

Ben Becker, the Houston father who helped organize a legal fight over last year’s STAAR exams, has repeatedly challenged superintendents over the last few months to join him in court to fight for their students.

Becker describes his group as a handful of Texas parents up against the state of Texas, backed by a legal team funded through a crowdfunding campaign. In a year when the STAAR exam went so horribly awry, and outraged so many school officials across the state, Becker says, “as parents [we] look around and wonder, where are the school districts?”

On Tuesday night, one school district is set to answer Becker’s call. Administrators in Marlin ISD, a rural district about 30 miles southeast of Waco, will ask the school board to join the lawsuit filed by Becker’s group in May.

“Marlin ISD will be the first to join this lawsuit as party plaintiffs,” Superintendent Michael Seabolt told Waco station KWTX on Friday, “and essentially that makes Marlin, as a school district, ground zero for state testing accountability reform.”

The stakes on last year’s STAAR exams were probably higher for Marlin ISD than any other district in the state. After four years of low ratings from the Texas Education Agency, the district faced possible closure if its students didn’t hit state goals for STAAR scores — and they didn’t.

Seabolt took over the district in July 2015 when Marlin ISD’s situation was already precarious. He and the district’s staff worked furiously to get the schools on track to meet the state’s targets, he told the Observer, so he’s been frustrated to see TEA sidestep the Legislature’s requirements for the test.

Seabolt agrees with the parents’ complaint that TEA flouted a 2015 law that should have shortened the STAAR exams. Records obtained by Becker’s group show that hardly any of the tests were completed in the time frame required by law.

So if TEA goes ahead with plans to take over or close Marlin ISD, Seabolt wondered, “You’re gonna take that action based on illegal test scores?” He drew a comparison to the state’s low target for special education enrollment, which the Houston Chronicle showed this month has deprived thousands of students of services to which they’re entitled.

“Why is it that TEA gets to pick which laws it’ll do and which ones it won’t?” Seabolt asked.

Marlin ISD has already had a monitor from TEA embedded in the district for the last five years, to right the ship, and Seabolt said he hasn’t been impressed. He said those changes focused too much on lowering teacher turnover and improving staff morale, and not enough on students’ experience in the classroom.

“What was happening here in Marlin before I got here was a travesty. There was too much focus on adult comfort and the children paid a price,” he said.

He doubts that closing the district would do much good — unlike Houston’s North Forest ISD, which was absorbed by Houston ISD when it closed, Marlin students are a 10-mile bus ride from the nearest district. By joining the court challenge, Seabolt hopes to forestall any other consequences TEA has in mind. He also plans to appeal the district’s latest accountability rating with TEA by the end of September.

“It’s all about more time to get the school where it needs to be,” Seabolt said. “We made some huge gains this year on testing, huge gains. But that’s one year. It’s gonna take more than that.”

After a Travis County judge ruled against the state’s attempt to have the case dismissed, Attorney General Ken Paxton appealed that decision to a higher court, which Becker worried could delay the case for months.

He mused that one of the state’s arguments to drop the case was that the group of parents didn’t have proper standing to sue over the test, and that a school district would be a more proper plaintiff. Now, it seems, the state could get its wish.

“I hope Marlin ISD jumps into the fray,” Becker said. “I also find it unfortunate that it requires literally an existential question about their future existence to get a district to join.”