Bridge to Nowhere

Where the Texas Gulf Coast meets Mexico, a trio of fossil fuel companies is planning an industrial complex the likes of which Texas’ Rio Grande Valley has never seen.

A version of this story ran in the September / October 2019 issue.

Where the Texas Gulf Coast meets Mexico, a trio of fossil fuel companies is planning an industrial complex the likes of which Texas’ Rio Grande Valley has never seen.

by Gus Bova

September 16, 2019

Somewhere along the road from Brownsville to South Padre Island, at the southern tip of Texas’ Gulf Coast, things take a turn for the picturesque. Clues of the Port of Brownsville’s transportation industry—cranes, storage tanks, floodlights—vanish. To your left, the Bahia Grande, a 6,500-acre tidal basin, yawns into the distance. To your right, a swath of salt-tolerant black mangroves recedes toward the ship channel, sheltering nesting birds and filtering water. Tricolor squadrons of blue herons, great white egrets, and roseate spoonbills stalk their prey as enormous brown pelicans battle through heavy currents overhead. Somewhere, a rare ocelot lurks in a patch of thornscrub.

This is a land of exceptions. The Bahia Grande forms the heart of one of the largest wetland-restoration projects in U.S. history; just 15 years ago, the basin was a desert, cut off from Gulf waters by the construction of the ship channel in the 1930s. One of only two ocelot populations left in America—about 60 of the endangered cats remain nationwide—clings to survival in the surrounding refuge. East, past a string of small coastal communities, lies the Laguna Madre, one of only a handful of lagoons in the world that’s saltier than the ocean, supporting unique wildlife and seagrasses. Across a causeway over the lagoon is South Padre, a tourist town at the tip of the longest barrier island in the world, home to some of the best beaches in Texas. In all, the area is among the state’s last coastline unspoiled by murky water and views riddled with smokestacks, refineries, and offshore rigs. All that, however, is likely to change.

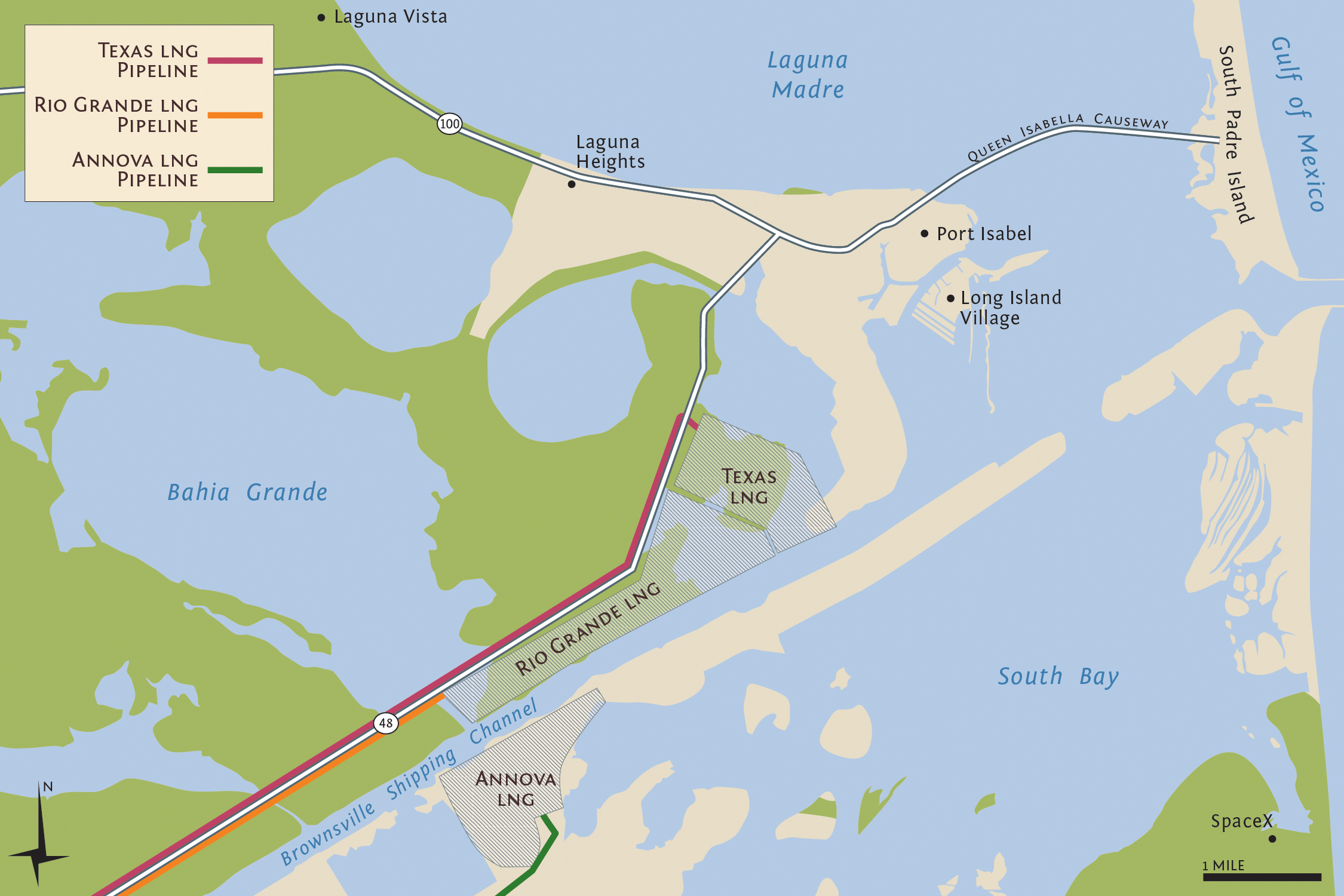

Beginning just across the highway from the Bahia Grande and extending nearly to the town of Port Isabel, a trio of fossil fuel companies is planning an industrial complex the likes of which Texas’ Rio Grande Valley has never seen. The scheme calls for the destruction of some 2,300 acres of wetland, thornscrub, and thickly vegetated clay hills, known as lomas, distinct to the area. A long-held dream of connecting Texas’ ocelots to their brethren in Tamaulipas would likely be dashed.

The companies are planning to build liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants, projects that would pipe in fracked natural gas from West and South Texas, hyper-cool it to liquid form, and send it off in hulking tanker ships to Europe and Asia. Towering over the plants would be 18-story storage tanks and flare stacks up to 315 feet high, periodically ablaze as they burn off gas. Ships the length of three football fields would pass through up to 511 times a year, hauling off as much as 38 million tons of liquid gas annually. The facilities would spew a witch’s brew of pollutants into the air: thousands of tons per year of headache-causing carbon monoxide and asthma-triggering nitrogen oxides, along with hundreds of tons of volatile organic compounds, including the carcinogens benzene and ethylbenzene.

The pollution would affect thousands of nearby residents. As close as a mile and a half to the proposed plants are Port Isabel, population 5,000; Long Island Village, a gated vacation and retirement community; and Laguna Heights, a colonia where 39 percent of people live below the poverty line. Those towns would also be on the frontlines of any gas explosion or fire.

“It’s an existential threat to our city and the Laguna Madre area,” says Jared Hockema, a South Padre resident and the city manager for Port Isabel, as we drive by the proposed plant sites in June. The liquefied natural gas plants aren’t just an environmental threat, he says, but also an economic one. While the area once relied heavily on commercial shrimping and fishing, tourism has become the local lifeblood. Birders view the spot as one of the top destinations in the country for migratory bird-watching; fishing and dolphin tours stay booked. “Our industries rely upon access and preservation of natural resources, and these projects threaten those resources,” Hockema says.

Or, as Bekah Hinojosa—a Sierra Club organizer and member of the local opposition group Save RGV from LNG—puts it: “LNG is contrary to our way of life down here.”

–

The companies aiming to contravene the way of life in this serene corner of South Texas are NextDecade, a publicly traded firm out of Houston; Annova, a Houston-based subsidiary of the Fortune 100 energy giant Exelon; and Texas LNG, a private firm also in Houston. Of the three projects, NextDecade’s—dubbed “Rio Grande LNG”—is by far the largest, accounting for around 70 percent of the projected production. To feed its facility, NextDecade plans to build a 136-mile-long double pipeline starting at the Agua Dulce trading hub near Kingsville. (The other two will hook into an existing nearby pipeline.)

The regulatory environment for these LNG projects demands fresh metaphors. Forget the fox and the henhouse; in this case, a swarm of locusts is guarding the greenhouse. Atop the Department of Energy is Texas’ own Rick Perry, who recently referred to LNG as “freedom gas,” suggesting the stuff could help liberate Europe from tyranny à la the Allied invasion of Normandy. (The enemy, this time, being natural gas produced in Russia.) Within, but technically independent of, the DOE is the agency with direct jurisdiction: the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). All three current FERC commissioners are Trump appointees, including a veteran of the Texas Public Policy Foundation, an oil-and-gas-drenched think tank in Austin. FERC has long been friendly to industry: Of 400 pipeline applications submitted between 1999 and 2017, the agency rejected two.

In an email to the Observer, FERC chair Neil Chatterjee, the country’s chief regulator of gas pipelines and LNG facilities, wrote: “I cannot overstate the importance of these projects; from their global strategic significance, to the environmental benefits, to the boon they represent to the already thriving U.S. economy, the projects are good news for America.” FERC has issued environmental impact assessments for the three projects. Although the agency would not provide a timeline, the companies predict they will get final FERC approval this year and make final investment decisions later this year or next, with LNG operations beginning in 2023 or 2024.

Local representatives are doing all they can to stop the plants. Port Isabel, South Padre Island, Long Island Village, and Laguna Vista have all passed resolutions opposing the facilities, and the Port Isabel school district denied tax breaks for the companies. But they’ve gotten no help from their Brownsville-based Democratic representatives. Congressman Filemón Vela and state Senator Eddie Lucio have both sent letters supporting the projects. The Cameron County Commissioners Court handed NextDecade a $373 million tax break in 2017, and state Representative Alex Dominguez, a county commissioner at the time, voted for the handout. All three declined to comment for this story.

The Brownsville Navigation District Board of Commissioners, an elected body that oversees the port, leased the necessary land to the LNG companies, making the entire scheme possible. But they needn’t worry about accountability. Residents of the communities closest to the proposed facilities don’t get to vote on them; they’re zoned in a different navigation district.

Still, activists are putting up a spirited fight. In 2017, Hinojosa and others traveled to Paris and helped convince France’s largest bank to yank support for Texas LNG. In June, the city of Port Isabel convinced the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) to grant what’s called a “contested case hearing”—a proceeding similar to a civil trial—on Texas LNG’s air permit, setting the project back a year. Now, the Sierra Club and others are demanding a second impact assessment for NextDecade’s project, based on conflicting statements from the company about how much LNG it will export, a move that could delay the project for months.

If—or, more likely, when—FERC issues final approvals, opponents will still have multiple avenues for court challenges, says Nathan Matthews, a California-based attorney for the Sierra Club. The fight, Matthews explained, isn’t just about local air quality, respiratory health, tourism, and property values. It’s about the future of a livable planet.

–

The Paris Agreement calls for limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius to avoid climate change’s most disastrous impacts, and a bracing United Nations report, released last year, clarified that doing so means zeroing out carbon dioxide emissions by 2050. But if you’re under the illusion that we, as a society, have recognized the urgency of getting off fossil fuels fast, then a little time spent in West Texas should disabuse you of the notion. A race is on, but it’s not to save the planet; it’s just another gold rush.

A little over a decade ago, people thought the Permian Basin—a 75,000-square-mile ancient seabed that’s produced oil for a century—was pretty much drilled dry. Then, entrepreneurial wildcatters figured out how to use horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing to unleash an untold bounty of oil locked away in shale deep beneath the earth’s surface. (The nearby Eagle Ford Shale is another hot spot.) What was already a rush became a frenzy in late 2015, when Congress and President Obama lifted a 40-year-old ban on exporting crude oil.

Today, the Permian yields around a third of total U.S. oil production, and in March, the basin surpassed Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar oil field as the most productive in the world. Fossil fuel titans like Exxon and Chevron are shunting the wildcatters aside, promising to ramp up output even further over the next few years.

Although West Texas drillers are mostly after oil, they can’t avoid the huge quantities of natural gas that also surface. With insufficient domestic demand and little pipeline infrastructure to move the stuff, drillers turned to burning off massive amounts of the gas, a process known as flaring. In 2017 alone, Permian operators flared enough fuel to meet the heating and cooking demands of Texas’ seven largest cities, according to the Environmental Defense Fund. Flaring releases pollutants, including particulate matter and sulfur dioxide, that attack the respiratory systems of Permian residents—who are also dealing with crumbling infrastructure and soaring costs of living thanks to the oil boom. Flaring is ostensibly restricted in Texas, but the state’s Railroad Commission keeps allowing it: From 2008 to 2018, the number of temporary venting and flaring permits issued increased by more than 5,000 percent. Still, all the flaring is sullying the Permian’s reputation, and, at least in theory, companies are burning money. Enter LNG.

The reason to liquefy natural gas, generally, is to transport it. The process decreases the gas’ volume 600 times over, allowing carriers to move far more product. The three LNG export facilities in South Texas are part of a nationwide wave of around a dozen such facilities currently proposed, overwhelmingly along the Gulf Coast. The product will go mostly to Asia, via the Panama Canal, and to Europe. Four facilities are operating now, including one in Corpus Christi, with another set to come online this September in Freeport. The Rio Grande LNG facility would be one of the largest in the country. This fall, new pipelines are set to move gas out of the Permian and Eagle Ford to the coast, adding to the 466,000 miles of pipeline that already crisscross the state.

The push to expand LNG exportation began under Obama, back when many environmentalists—including the Sierra Club—saw natural gas as a cleaner alternative to coal and a “bridge fuel” to get to renewables like wind and solar. But opinion has turned, and sharply. In May, Oil Change International released a report endorsed by more than a dozen major environmental organizations that concluded: “The myth of gas as a ‘bridge’ to a stable climate does not stand up to scrutiny.” Some Democratic presidential contenders now support banning fossil fuel exports and fracking altogether. (Either move could leave LNG dead in the water.)

The problem, fundamentally, is this: Natural gas is almost entirely methane, a greenhouse gas that’s around 87 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20-year span. Methane leaks along the entire gas supply chain—a chain made longer by LNG exportation—thus eroding the fuel’s advantage over coal. Even if leaks are kept to a minimum, natural gas is still a dirty fuel: Burning it releases about half as much carbon dioxide as coal.

In a July report, the Sierra Club, Save RGV from LNG, and others estimate that—accounting for leaks, processing, shipping, and combustion combined—the three South Texas LNG plants represent the same global warming impact as 61 coal-fired power plants. Operation of the projects alone, per FERC documents, will emit around 9 million tons of greenhouse gases per year. And every dollar we sink into dirty fuel takes us a step away from the climate goals we must hit.

“This is fossil fuel infrastructure that’s being built out,” said Robert Forbis, a Texas Tech professor who studies environmental protection and energy development. Once the plants and pipelines are built, Forbis said, companies will be incentivized to keep hawking LNG for decades to come. “It’s a bridge that keeps getting longer and longer and longer,” he said, adding that private capital and export capacity should be dedicated to renewable energy instead. Or, as Hinojosa, the Sierra Club organizer, put it: “It’s a bridge to nowhere.”

–

On a Wednesday evening in June, Noe Lopez, 60, takes the wheel in the bridge of the ship he captains almost every day. For $10 a person, he takes customers in Port Isabel out to find bottlenose dolphins in the Laguna Madre, where he’s fished since he was 8 years old. About 15 people lean over the ship’s rails, waiting to see the creatures. Gruff-looking and foulmouthed, Lopez has a sudden, beaming smile that catches you off guard. He puffs away on Marlboro 100s as he banters into the microphone for the crowd, cracking jokes and referring to every dolphin as “Flipper.” Seagulls fly by the boat, so close you could almost touch them. We see probably a dozen dolphins break the surface of the lagoon during the hour and a half we’re out. Lopez also takes customers out bay-fishing for sand trout, whiting, and croaker.

I ask Lopez if he’s worried about the LNG facilities, and he responds without missing a beat. “Shit yeah,” he says. For Lopez, the impacts could be threefold. The facilities would drive down tourism, eating away at his customer base; the mammoth LNG vessels would take up so much of the channel that they’d limit where he can search for dolphins; and the increase in large-ship traffic would tank his bait supply. Bait shrimpers trawl the channel and sell their catches to bay-fishers who work the Laguna Madre; large tankers stir up sediment from the channel bottom, ruining the shrimping for hours at a time. As Lopez puts it: “They screw up the channel, there goes the fucking bait.”

I ask Lopez about the jobs the LNG companies promise to bring. Like many of the residents I spoke with during the week I spent in the area, he’s unimpressed. “How many of those jobs are for the people from this little town in the Valley? … Nobody’s qualified for shit like that.”

According to Cameron County officials and documents submitted to the county, the Rio Grande LNG project will generate thousands of temporary construction jobs and around 300 permanent on-site jobs. Of those, around 35 percent will be local hires—defined generously as those residing in Cameron County or within 100 miles of the site, meaning workers could come all the way from McAllen. Annova told the Observer it will create 165 permanent on-site jobs; Texas LNG declined to provide any information. The companies argue their projects will also have a knock-on effect, generating demand for goods and services in the local communities. But opponents are skeptical. Tourism also creates demand for goods and services, and the jobs gained in LNG might just be canceled out by those lost in the tourism industry. In the Valley, around 6,600 jobs depend on nature tourism alone, according to researchers at Texas A&M University.

“People are working in restaurants, hotels, on boats, and they have good employment right now,” said Hockema, the city manager. “If these facilities diminish their employment opportunities, those opportunities will not be able to be replaced.”

Eduardo Campirano, director of the Port of Brownsville, sought to allay concerns about access to the ship channel. Larger vessels won’t be able to enter while the LNG tankers are there, but smaller vessels will generally be able to pass them by, he said. The port already handles large vessels carrying steel or petroleum products—including the occasional aircraft carrier—and even though the LNG vessels will add to that traffic, he said, the channel won’t become “congested,” like some ports farther up the coast. “You might see [big vessels] on a more frequent basis, but you’re not going to see them to the extent that the channel is going to be shut down, or that other vessels will never be able to utilize the ship channel.” (A Coast Guard spokesperson also said other vessels will be able to use the channel, though they may need permission from the Guard.)

Other locals are most concerned about the air they breathe. In the colonia of Laguna Heights, Octaviana Sosa, 44, lives in a cramped one-story home with her husband and three young children. As we chat at her kitchen table, the kids pester her for snacks and fiddle with an iPad. The neighborhood, home to many Mexican immigrants who work in the area’s hotels and restaurants, is pockmarked with dilapidated trailers and mobile homes. Because the prevailing wind is from the south, the colonia sits in the path of air pollution from the facilities. Sosa’s 8-year-old son already suffers from respiratory problems, making regular use of a nebulizer. “More than anything, I’m worried about him,” she says. “The pollution could make things worse for him.”

Erin Gaines, an attorney with Texas RioGrande Legal Aid who’s representing Sosa and other Laguna Heights residents in proceedings before federal and state regulators, said the situation is yet another case of poor residents of color bearing the brunt of pollution.

In response to public comments about the Rio Grande LNG facility, TCEQ director Toby Baker said that while the plants will emit pollutants, “adverse impacts to human health and welfare … are not expected.” TCEQ has granted an air permit for the Rio Grande project, but not yet for the other two.

Still other residents worry about disaster. Ed McBride, 71, lives in Long Island Village, a well-to-do hub of Winter Texans and retirees who live in quaint sea cottages alongside an 18-hole golf course. The community is only a mile and a half from the proposed Texas LNG facility and sits right along the channel, where tankers will pass. A retired fire captain from Colorado, McBride has a nightmare scenario: that LNG will leak, evaporate into a cloud that, heavier than the surrounding air, will slink along the ground into one of the surrounding communities, find an ignition source, and blaze into a short-lived but uncontrollable fire. FERC documents identify Long Island Village as within the zone where a fire from a tanker spill could cause “significant” damage. The Coast Guard, though, has determined that all three projects are sufficiently safe.

The LNG industry touts an admirable safety record compared with its peers in the fossil fuel business; still, things have gone wrong. In 1979 in Maryland, a defective seal at an LNG import facility led to a blast, killing one. In 2014 in Washington, improper equipment cleaning led to an explosion at a storage facility, injuring five. In 2018 in Louisiana, federal regulators found that long gashes had opened up in a tank at an export facility, releasing flammable gas, and in July in Karnes County, a compressor along a gas pipeline failed, sparking a towering blaze.

Recently, the LNG industry has started using safer storage methods. In an email, an Annova spokesperson also noted that federal guidelines require that LNG facility layouts prevent a fire or explosion from leaving the area, so that the “unlikely possibility of flame ignition would not extend beyond the property boundary.”

In a way, the LNG facilities in South Texas are a Trojan horse. As part of a deal with the port, NextDecade has agreed to dredge much of the channel 10 feet deeper—in part to help the company’s own tankers pass, but also to pave the way for other huge vessels and, potentially, other oil and gas developments. Already, a company called Jupiter MLP plans to build a crude oil upgrader facility at the Port of Brownsville, near the channel’s west end; the firm also hopes to add a massive oil pipeline stretching from West Texas and an offshore station from which behemoth oil carriers could haul the stuff away. Today’s battle, then, is for the region’s future. Call it the fight against Corpus Christification.

For Hockema, the solution is to nip the oil and gas build-out in the bud and play to the area’s strengths, drawing more tourists, retirees, and Texans who can work remotely. Patrick Anderson, a Los Fresnos schoolteacher who ran unsuccessfully last year for the navigation district board, argues that the port should use its land to promote renewable energy. A solar panel manufacturing facility, he suggested, would also create more permanent jobs than LNG.

For Sosa, the mom of three who lives in Laguna Heights, the economics are beside the point. “Maybe they bring money, but what about the nature, what about the beauty?” she asked. “What’s going to be left for our kids?”

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 220 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

Read more from the September/October issue of the Observer:

- They Persisted: These candidates are back in the ring to prove that 2018 wasn’t a singular “year of the woman.”

- Thousands of Rape Kits in Texas Went Untested For Years. Lavinia Masters Is Ending That: The Lavinia Masters Act is the culmination of more than ten years of Masters’ advocacy in Texas, where a backlog of about 20,000 untested rape kits was identified in 2011.

- Could Trump’s Reelection Campaign Turn the Texas House Blue? A number of high-profile GOP electeds are throwing in the towel in advance of the 2020 election cycle—with more expected in the coming year.