Internment Camps Take the Stage in Houston, and We Wish It Were Just a History Lesson

A dance performance at the Asia Society marks the 75th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s executive order authorizing World War II internment camps.

Like many Texans of her generation, choreographer Sue Schroeder learned nothing in school about the U.S. internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, more than 100,000 innocent people of Japanese ancestry, most living on the West Coast, were incarcerated, often in far-flung places like Arkansas and Texas. But when she was a student at Houston’s High School for the Performing and Visual Arts in the 1970s, Schroeder reports, the topic never came up.

For that reason, Schroeder was eager to tackle the subject for her CORE Performance Company, which has been part of the Houston dance community since 1980. “Initially it was trying to give voice to a historical event that so many people do not know about,” Schroeder says. “I felt a real charge of responsibility to do that.”

Schroeder’s choice would turn out to be timely, but she didn’t know that a year ago, when she began choreographing “Life Interrupted,” CORE’s latest show, on stage in Houston at the Asia Society February 17 and 18. Struggling to make the story of Japanese-American internment relevant to modern-day audiences, Schroeder hired a dramaturg to help develop the story and began working with collaborators, including Richard Yada, who survived the camps, and artist Nancy Chikaraishi, whose parents had been incarcerated.

“My dad calls it the defining moment in his life,” says Chikaraishi, whose parents met in the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas. “People lost everything they had. My parents’ families did not go back to California after the war. They started over with $50 and a bus ticket.”

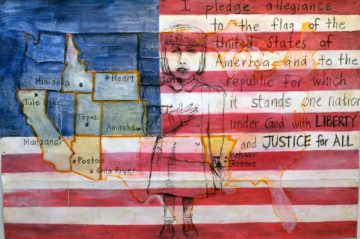

Chikaraishi, a professor of architecture at Drury University, contributed mixed-media illustrations to the “Life Interrupted” performance. These images are projected onto a screen at the back of the stage, and often also onto foreground props or onto the bodies of the performers as they leap, cower and face off against each other in the physical language of contemporary dance.

One moment of the performance uses Chikaraishi’s artwork to great effect: An audio recording plays of children reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in unison, as was a required morning ritual in the camps. Meanwhile, an illustration of a young girl with her hand over her heart in front of an American flag is projected onto three rucksacks representing the few belongings that detained families carried into the camps on their backs. Alongside, a female dancer twists and gyrates in a push-pull display of defiance and obedience, objection and grievance.

To bridge the historical distance, Schroeder focused on the timeless theme of the “other” as a social category. “That has been the constant through this work: Who is the other, what are our fears about that, and what does it feel like to be the other?” Schroeder says. “We have woven text into the score, but the dancers don’t speak onstage. As an art form, it’s still very body-based, image-based and present. … The arts can create empathy, and I think that’s what we need to understand the other.”

As she began working with her dancers last year, Schroeder watched the global refugee crisis grow. She saw parallels between modern refugees, forced to flee for reasons of safety and human rights, and the Japanese-American internment. “The piece started to have a present-day context,” she says.

Then, on the last day of a developmental residency in Arkansas, Schroeder and her dancer-collaborators watched history happen. “We were at the Little Rock airport, and the Paris attacks were happening, and [news commentators] were talking about locking up Muslims,” Schroeder recalls. “We just looked at each other. … It became a much larger commitment.”

“Now we’re in this time when [Trump] is trying to use Japanese internment as precedent to do the same thing again,” Schroeder says. She’s referring to comments made in November by Carl Higbie, a former spokesperson for the pro-Trump Great America PAC, suggesting that Trump’s legal team may plan to invoke Korematsu v. United States, a Supreme Court case that upheld President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s February 19, 1942 executive order authorizing the camps, as precedent for a Muslim registry.

“We’re repeating history,” Schroeder says. “So now the piece is taking another turn.”

Schroeder is realistic about the potential of the arts to forestall a national disaster. But she says, “I think, at a minimum, we’re giving voice and a forum for conversations to happen.”