Hundreds Gather to Remember the 1966 Texas Farmworkers’ March

The 491-mile walk led to the first statewide minimum wage and effectively launched the farmworkers’ movement in Texas.

Hundreds of demonstrators gathered in Austin Sunday to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1966 farmworkers’ march from the Rio Grande Valley to the Capitol — an event that led to the first statewide minimum wage and effectively launched the farmworkers’ movement in Texas.

“It was the spark that initiated the Chicano movement here in the state of Texas,” said Rebecca Flores, former director of Texas United Farm Workers, “and I don’t want it forgotten.”

On Sunday, hundreds of participants followed for a short time in the original demonstrators’ footsteps, gathering for mass at St. Edward’s University — where marchers slept overnight in 1966 — before marching four miles down Congress Avenue to the state Capitol. Once on the grounds, the marchers listened to live music and heard from a series of speakers, including Mayor Steve Adler and a handful of farmworkers who marched in 1966.

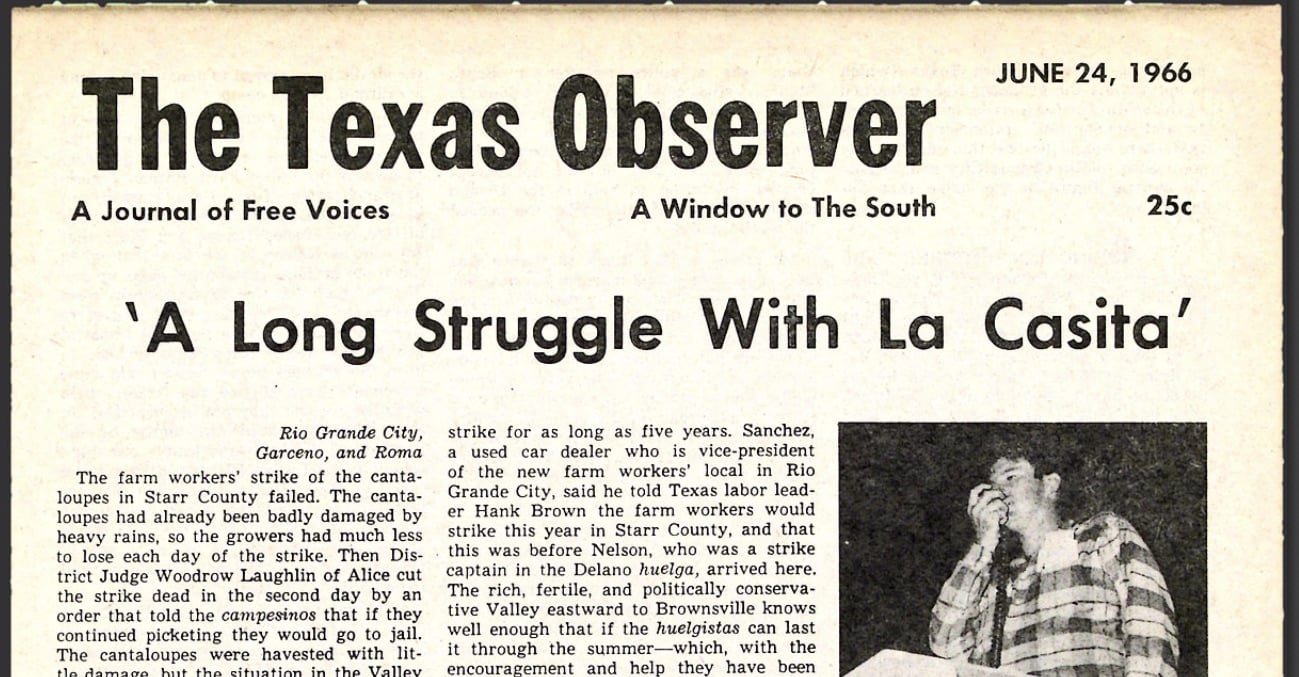

The original march was a blistering, 491-mile trek from Rio Grande City to Austin that began as a strike in the melon fields of Starr County. At the time, the mostly Mexican-American farmworkers picked crops in the hot South Texas sun — often without sufficient drinking water or a place to use the bathroom — for between 40 cents to 60 cents an hour, far below the $1.25 minimum wage that applied to most other laborers.

As the Observer documented at the time: With assistance from the United Farm Workers, the melon pickers struck in the fields of Starr County on June 1, 1966. As the strikers faced arrests and physical assaults from the Texas Rangers, plus the approach of the late-summer months — when many workers would migrate elsewhere for another harvest — the strikers decided to switch tactics, launching a march to the Capitol to keep attention on their struggle. They now called on then-Governor John Connally to meet with them and call a special session of the Legislature in order to establish a $1.25 minimum wage for all Texas workers.

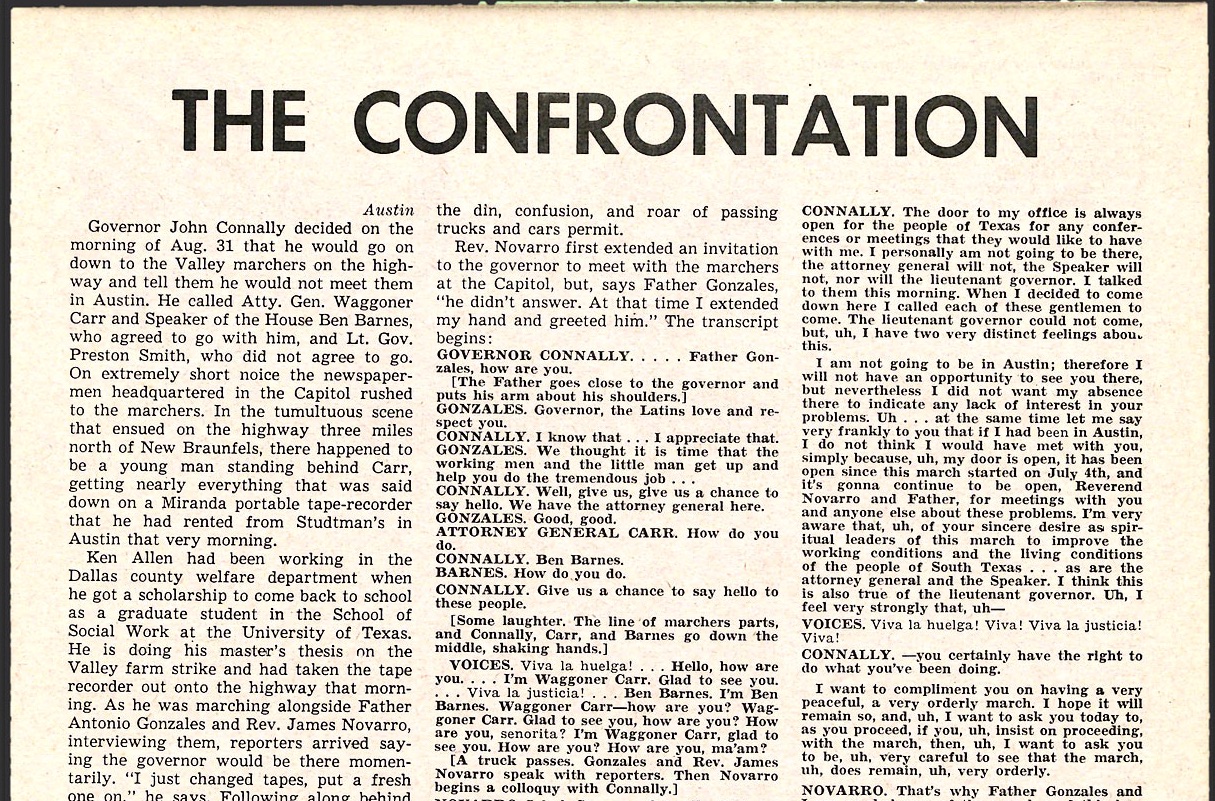

Rather than meet this demand, Governor Connally met the marchers in New Braunfels, informing them that he would not be present at the Capitol to greet them. “I am not going to be in Austin; therefore I will not have an opportunity to see you there,” said Governor Connally at the time. “At the same time, let me say very frankly to you that if I had been in Austin,” he continued, “I do not think I would have met with you.” He justified this snub by saying that potentially violent marches were not necessary to obtain a meeting with the governor.

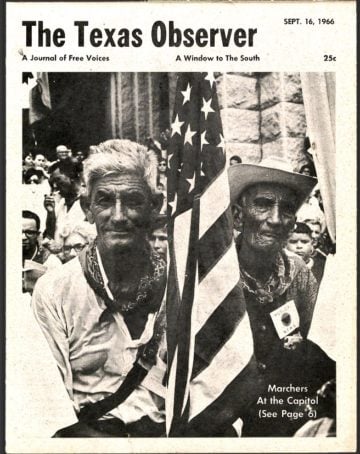

Undeterred, the marchers soldiered on to Austin. They arrived on Labor Day 1966 and, their ranks swelling to 10,000 by contemporary estimates, they rallied on the Capitol grounds.

Jim Harrington, founder of the Texas Civil Rights Project, summarized the event as the “Rosa Parks moment of the Hispanic movement in Texas.”

“It was the catalyst,” he told the Observer, “that brought everything together, and a lot of the young people in it went on to get involved in politics.” The march is also widely considered the impetus for both the 1969 Texas minimum wage law and a legal ruling that voided statutes barring certain types of public assembly and blocked the Texas Rangers from further interfering with the strikers.

Fifty years later, as hundreds of marchers from labor, faith and community groups spilled onto South Congress Avenue from St. Edward’s University, five participants drew special attention: Guadalupe Guzman, Romeo Garza, Daria Vera, Thelma Carrera and Efrain Carrera, all farmworkers who marched from Starr County in 1966.

Among them, Guzman was the only one to walk all 491 miles without taking a break from the march. Now 78 years old, she told the Observer, she still recalls support for la huelga — the strike. “I remember people we would pass yelling ‘¡viva la huelga!’, and I remember people crying.” During Sunday’s march, she took a car most of the way.

Guzman’s son, Romeo Garza, also present on Sunday, was 6 at the time of the 1966 march, and he recalls protesting outside a jail in Starr County where organizers were detained by the Texas Rangers. Garza told the Observer that at the age of 10, he became a farmworker, competing with his friends to see who could pick the most cantaloupes. “I liked it back then,” he said while marching at the head of yesterday’s procession, “as I got older, it got hard though.”

Lawrence Banda, who joined the last leg of the 1966 march, remembers picking cotton and corn for around 30 cents an hour in Hornsby Bend in Travis County. “Later I became a carpenter,” the 76-year-old told the Observer, “but I learned my numbers in the field to figure out how much cotton I’d picked in a day — at one-and-a-half cents a pound.”

Throughout the Sunday march, the Austin-based Workers Defense Project, which fights for construction workers’ rights and was the day’s rowdiest contingent, frequently exhorted the procession with refrains of “sí se puede” and “el pueblo unido, jamás será vencido” — the people united, will never be defeated.

Marta Sanchez, who marched with La Unión del Pueblo Entero (LUPE), told the Observer that labor and economic conditions in the Valley have transformed since the 1966 march. Nowadays, workers are employed in construction, the service industry and in flea markets rather than agriculture. Still, she said, the fight for low-income workers in the Valley continues.

Many in the area live in colonias, subdivisions where residents lack access to basic services such as sewers and on-the-grid electricity. “There are also many more undocumented people in the Valley than in 1966,” she said. “Ever since 9/11 … the immigration checkpoints trap people there.” Her organization serves that largely undocumented community by providing social services, advocating for infrastructure such as public lighting, and hosting “lots of protests and marches.”

![As the marchers approached Austin, the Observer ran a front-page piece penned by Eugene Nelson himself, the United Farm Workers organizer who was sent to South Texas earlier in the year. In it, he describes his experiences as an aspiring novelist and his meandering journey into labor organizing. The issue contains several other articles on the march, including another piece by Observer founding editor Ronnie Dugger, in which he reveals a tension within the march's leadership. As Dugger put it: "'Viva la Huelga,' long live the strike, was the battlecry of the strikers under Eugene Nelson in Rio Grande City, but as the more politic and more middle-class clergymen, Rev. James Navarro and Father Antonio Gonzales of Houston, moved into their central roles in the march to the Capitol, the strike was heard of less and less, the [$1.25] minimum wage more."](https://www.texasobserver.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/201609-lamarcha-nelson-fp-two-archives.png)

As musicians at the Capitol rally on Sunday wrapped up a version of “De Colores,” a classic song associated with the farmworkers’ movement, Rebecca Flores took the podium to emphasize the need for more work like LUPE’s. Many Mexican-American leaders arose out of the farmworkers’ struggle, she said, becoming organizers or elected representatives who helped win improvements like higher minimum wages, bathrooms in the fields, and regulations that protect farmworkers from inadequate and unsafe housing.

“But many of those legislative gains we won in the 1980s aren’t being enforced now,” Flores told the crowd. “So we have to be there for the upcoming legislative session to fight for that.”

[Featured image of Sunday’s march by Gus Bova]