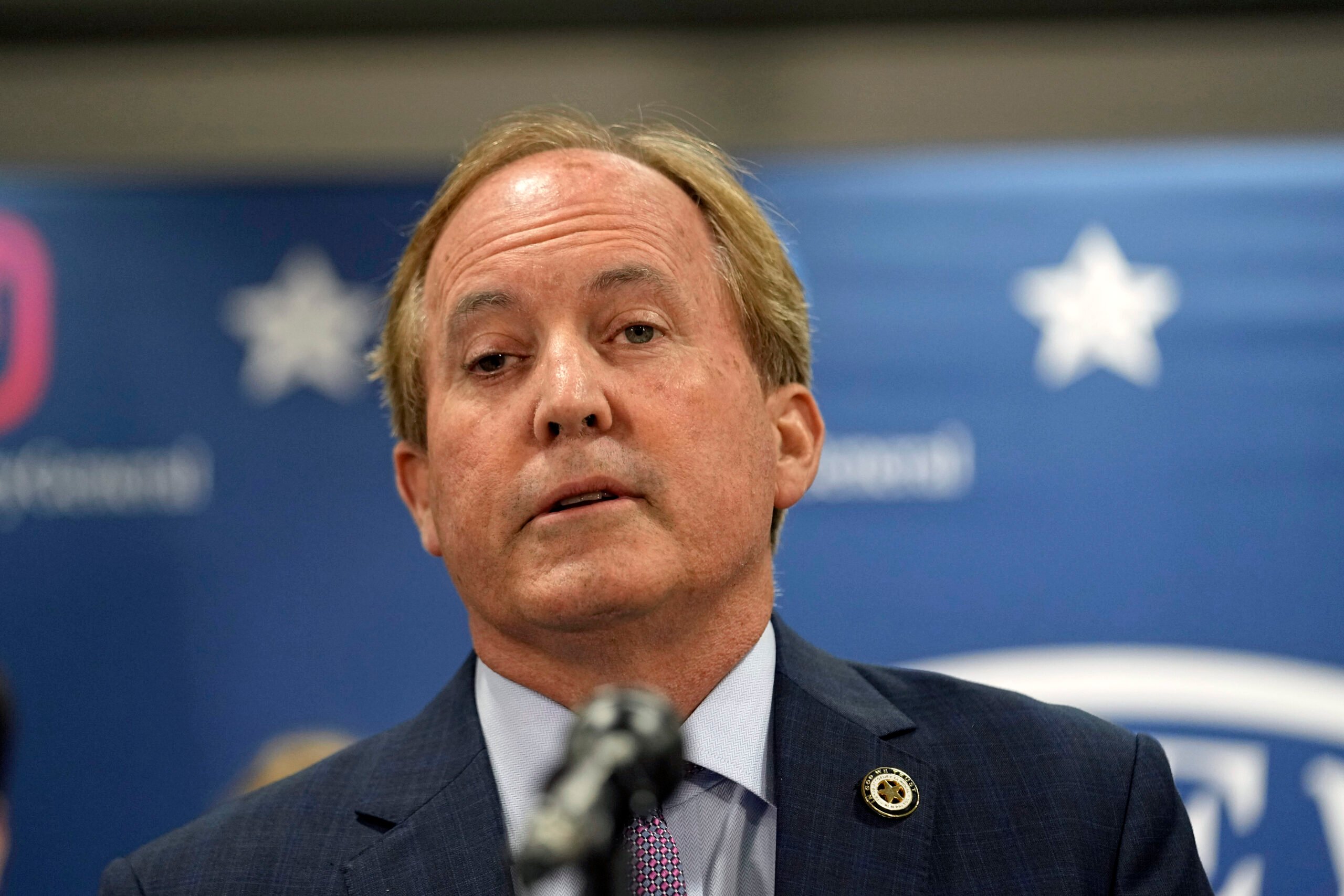

Just When Ken Paxton Thought He Was In the Clear…

Above: Ken Paxton, after being sworn in, stands among Texas GOP VIPs: From left to right, Gov.-elect Greg Abbott, Sen. Ted Cruz, Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst, Justice Don Willett, and Gov. Rick Perry.

On Wednesday night, news broke that a Collin County grand jury is exploring anew Attorney General Ken Paxton’s potential legal improprieties—another milestone in his declining fortunes. For the last few months, Paxton had seemed to have gotten away with it.

First, he had managed the spectacular task of getting elected to the top law enforcement job just months after admitting to violating securities law by shunting his legal clients into shady financial deals, then getting a kickback, without telling them about it. That was the easy part. (He’s a Republican; it’s Texas.)

But if someone were to simply indict him for the crime that he had apparently admitted to committing, he would likely be charged with a felony. No sweat, right? Paxton is not even a ham sandwich—he’s the lowest of low-hanging fruit. A prosecutor would just have to reach out and pluck him. But in late January, Paxton got an even bigger break. The Travis County District Attorney’s Public Integrity Unit—the ethics watchdog that Republicans are convinced is out to get them at all costs—politely declined the case.

The PIU prosecutor said that only the district attorneys in Collin and Dallas counties, where Paxton was active at the time he allegedly violated the law, had the jurisdiction to charge him. Both Republicans, the DAs seem exceptionally unlikely to go after Paxton. Dallas DA Susan Hawk’s office has been barely functional amid a series of weird personal dramas, and Collin DA Greg Willis is a long-time best friend of Paxton’s—they’re former business partners, and supported each other’s election bids. If you go to Willis’ website, Paxton is still listed as heading up the host committee to one of Willis’ last big fundraisers.

So like the ill-fated villain of a noir, Paxton had arrived at the moment of false confidence that bad guys always reach right before the hammer comes down. After an election season in which his spokespeople were literally manhandling reporters to keep them from asking questions—any questions at all—of the big man, Paxton had something of a coming-out party. He was feted by GOP royalty, without reservations, at his inauguration. In February, he appeared with Gov. Greg Abbott, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, and U.S. Senator Ted Cruz at a high-profile Obama bashfest. He even wrote a column for Bill Buckley’s old rag.

If everyone on the GOP team just kept quiet, Paxton would be fine, and in four to eight years he’d move on to higher office. And it seemed initially like that’s how it would play out. When Craig McDonald, the head of the left-leaning accountability group Texans for Public Justice, tried to follow up with Willis’ office on the information on Paxton sent by the PIU, he says he “got the clear sense from Willis’ spokesman that our stuff was going straight into the paper shredder.” (Willis’ office didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

Which is why three events in the last week have come as such a surprise. The first came last Thursday, when the editorial board of the Dallas Morning News called for Willis to seek the appointment of a special prosecutor to look into Paxton’s history. “The state’s top law enforcer, Attorney General Ken Paxton, also happens to be an admitted law breaker,” the editorial began. It continued:

These are not nitpicky issues. State securities law imposes registration requirements to protect the public from victimization by investment frauds and scams.

The fact that Paxton violated the law repeatedly over several years suggests a troubling pattern unbecoming of the esteemed office he now holds. That’s why an independent prosecutor needs to assume control of this case.

Then, on Friday, state Sen. Kel Seliger (R-Amarillo) told the Houston Chronicle that he thought the case warranted more attention:

“How is going back to your home county and having a friend and business associate handling your prosecution better?” Sen. Kel Seliger, R-Amarillo, said. “I think it’s a clear case for a special prosecutor.”

Republicans are generally very good at tribal loyalty, but many serious GOPers can’t be happy with the fact that one of their most important statewide elected officials is so ethically challenged. (Though amid the ensuing firestorm, Seliger told one Lubbock radio station he’d been talking in hypotheticals.)

Republicans are generally very good at tribal loyalty, but many serious GOPers can’t be happy with the fact that one of their most important statewide elected officials is so ethically challenged.

Seliger and state Sen. Kevin Eltife (R-Tyler) held up the bill over a proposal that the AG’s office play a role in ethics investigations—letting Paxton guard the henhouse. But once that was stripped, the two dropped their objections. On Wednesday, SB 10 passed the Senate along party lines, 21 to 10.

During the debate, state Sen. Kirk Watson (D-Austin) outlined a hypothetical scenario that mirrored the case of Paxton and Willis. Would Huffman, who used to work in the office of the Harris County DA, think it appropriate for the Willis-like figure to step aside and urge the appointment of a special prosecutor? Huffman answered that if she were the DA, “I would recuse myself.” But her bill would force more and more local DAs into that position, where not all might have Huffman’s sense of ethical responsibility.

But just a few hours after the Senate debate concluded, the Houston Chronicle broke word that Willis might not have to ask for a special prosecutor after all. A Collin County grand jury had gone rogue, in part, perhaps, because of the public attention conjured by the Dallas Morning News and others. The grand jury appeared to be circumventing Willis. They requested the information forwarded to his office by the PIU—the information Willis seemed intent to ignore.

“Collin County appears to be the venue where this evidence needs to be heard,” says the letter from the grand jury vice foreman. “Therefore, we are requesting the documents be sent to us as soon as possible.”

Once the grand jury hears the evidence in Paxton’s case, an indictment seems more likely than not.

“This case is absurd because Paxton has already admitted to a crime with Texas regulators,” says McDonald. His admission of guilt, passed off by his consultants during the election as the end of the matter, “in no way adjudicates his potential felony criminal behavior.” As a reminder of the surreal nature of the fact that he may not be prosecuted for a crime which he has apparently admitted to committing, McDonald says, he keeps Paxton’s “signed confession” on his desk.

Editor’s note: This story has been edited to remove a questionable historical reference in the original version.