A Desire Named Streetcar

How did Julian Castro’s streetcar project become a political train wreck?

Above: A concept image of what the San Antonio "Modern Streetcar" would have looked like.

On July 28, former San Antonio Mayor Julian Castro raised his right hand and was sworn in as the new secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. That same day, back in the Alamo City, one of Castro’s signature programs, the “Modern Streetcar” project, was going off the rails, undone by the very leaders who’d once backed it.

A couple hours after Castro’s swearing-in, the new interim mayor, Ivy Taylor, stepped out of a City Council executive session and announced the controversial streetcar project was effectively dead. Things were quickly changing in this new Julian Castro-free San Antonio.

“Castro leaving killed the streetcar but it also opened the floodgates to some crazy politics that is going to impact San Antonio for some time,” said Henry Flores, a political science research professor at St. Mary’s University.

Flores said Castro’s sudden departure is welcomed by the city’s Tea Party activists, who see an opportunity not just to ax the ex-mayor’s projects, but make gains in a Democratic stronghold.

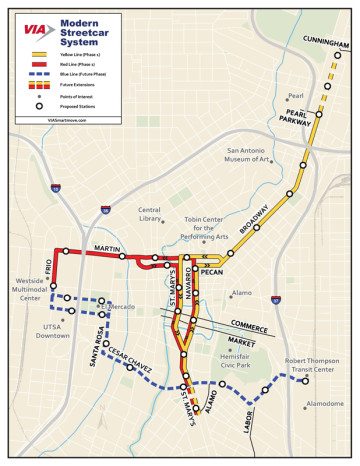

The 5.9-mile rail system would have carries passengers around the booming but congested downtown and also traveled north on Broadway to the Pearl Brewery, a thriving development with shops, bars and condos.

The estimated price tag: $280 million, with $32 million provided by the city—a relatively low cost for re-introducing rail to San Antonio. The Austin transportation proposal, which goes to the voters in November and includes a proposed 9.6-mile rail system, would cost $1.4 billion. The San Antonio streetcar system would have required no tax increases, and if all went well it could have served as a starter system for an eventual citywide light rail.

While Castro characterized it as a step forward for San Antonio, the proposal also harked to the past. San Antonio had a thriving streetcar system from 1877 until the 1930s, first with a mule-drawn trolley from Main Plaza to San Pedro Park. At its peak, the system boasted 90 miles of track and 1.5 million fares in a single month in 1922, when the city had just over 160,000 people. But in 1933, the Alamo City became the first major American city to kill its electric streetcar network.

The Modern Streetcar project had been in development for five years, and VIA Metropolitan Transit, the agency that would build and operate the streetcar system, was only weeks away from placing the order for the streetcars themselves. Castro and other supporters had said repeatedly the project was past its event horizon, impossible to pull back. But that was before Castro abruptly announced he was leaving for Washington.

Modern Streetcar was a key component of Castro’s big vision for San Antonio, what he called “The Decade of Downtown.” He had spent much of his five years as mayor working on revitalizing the city’s core. There were a number of successes. Construction on a convention center redevelopment project is now underway. Hemisfair Park, the grounds of the 1968 World’s Fair, is being reimagined. Over 3,500 new downtown residences have been built, with more on the way. A new major highrise was recently announced. New jobs are coming to the Centro area, and H-E-B has finally agreed to build a large grocery store downtown. The streetcar would tie it all together.

“Castro leaving killed the streetcar but it also opened the floodgates to some crazy politics that is going to impact San Antonio for some time.”

When VIA first went public with its plan for the streetcar project in 2011 there was immediate resistance—coming from what you might term “the usual suspects,” gadfly anti-spending stalwarts opposed to most City Hall initiatives.

“There were just four of us. We were tiny, tiny grassroots,” said George Rodriguez, South Texas coordinator for the Tea Party Patriots.

Rodriguez would show up at VIA public hearings with anti-streetcar signs and try to get on the local news. His group would also file public information requests with VIA, trying to get detailed financial information. “We were being flat stonewalled,” he said. “We were being ignored.”

The opposition was so unimpressive that the streetcar plan passed City Council in October 2011 with a 9-to-1 vote. But that setback didn’t stop Rodriguez. Over the next three years the chorus grew louder and larger. Little by little Rodriguez and his group chipped away at support for the streetcar project—with a lawsuit, press conferences, protests, letters to the editor and call-ins to talk radio. They challenged the need for a rail project; they argued that regular buses could do the job better and cheaper; and they suggested that streetcars would actually add to downtown’s congestion.

The opposition also attracted folks who had little interest in transportation issues, but saw a chance to take a swing at Castro.

Over Castro’s time as mayor, a faction grew in San Antonio that reflexively attacked his causes and projects. That faction grew in size and political stature when it became clear that Castro had his sights set on higher office. When he was picked by President Obama to give the keynote at the 2012 Democratic National Convention, Castro became a handy surrogate target for local conservatives who lacked the range to clip Obama.

The entire anti-Castro coalition climbed aboard the anti-streetcar bus, including the local Tea Party, anti-toll road stalwarts, social conservatives who’d fought against a non-discrimination ordinance for LGBT people, the Koch-financed Americans for Prosperity, and GOP supporters looking to halt Castro’s rise as a Democratic star. There were even some unlikely allies like the local firefighters union, which was battling City Hall over a new contract.

“We were doing the groundwork of educating the public about the problems with the streetcar,” said Jeff Judson, senior vice president of the San Antonio Tea Party. “But we didn’t have a ground game until the firefighters joined in.”

But to some the firefighters’ objections appeared to be insincere. “Those firefighters didn’t care one whit about the streetcar. For them it was all about keeping their benefits,” said Flores. “And to do that they needed to show some political muscle.”

The involvement of the San Antonio Professional Fire Fighters Association Local 624 transformed the streetcar opposition from a mere nuisance to a major problem for City Hall. The turning point came came on July 7, when Greg Brockhouse, the union spokesman, walked into City Hall carrying cardboard boxes crammed with petitions.

Brockhouse, a failed City Council candidate and a former chief of staff for Councilman Rey Saldaña, knew how to get the council’s attention: 26,749 signatures on a petition that could put the streetcar issue on the November ballot.

“We want a focus, a back-to-basics focus, on where our tax dollars will be spent,” Brockhouse said as he presented the petition.

Brockhouse howled that there was no citizen referendum on the streetcar issue and stoked public mistrust of the project and city leaders. The anti-streetcar coalition successfully diverted the discussion from the merits of the project to arrogant politicians trying to shove a boondoggle down San Antonians’ throats.

“There were just four of us. We were tiny, tiny grassroots.”

“These city hall types just want to spend tax dollars so they can build legacy projects they can name after themselves,” said Rodriguez. “We don’t need these things; it’s just for their ego.”

Looming in the background was the specter of the May 2000 referendum on light rail—a disaster for rail enthusiasts. Seventy percent of voters shot down the $1.5 billion, 53.5-mile system, which would have stretched to the far corners of the growing city. To pay for it voters needed to agree to a quarter-cent sales tax increase. But the plan was too aggressive. (Later that same year, Austin voters narrowly defeated a similar plan by just 2,000 votes.) Fourteen years later, the defeat of light rail still haunts Bexar County politics.

Brockhouse deftly played on the old fears. Twenty days after he delivered the petitions to council, Castro was taking the helm of HUD in Washington, and the city’s top officials were announcing that the project was all but dead.

Longtime Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff, a Democrat who faces an anti-streetcar Republican opponent in November, told reporters on July 28 that he still believed in the plan but that it had been effectively defeated.

“You win some, you lose some,” Wolff said. “We’ve lost this one.”

Interim Mayor Ivy Taylor said City Council wouldn’t pledge any money until there was a public vote.

But there was still the issue of the petition—the equivalent of a live grenade among the city’s suddenly shifting political scene. A streetcar question on the November ballot, even if it was technically dead as an idea, could add a complication for a lot of candidates.

On August 6, City Attorney Robbie Greenblum announced there was a problem with the petition: Too many pages lacked the signature of the person who circulated the petition. Greenblum threw out those pages where no one had signed off as “circulator.” Now the anti-streetcar drive was 8,000 names short—the streetcar initiative wouldn’t be on the ballot.

Even though the petition drive failed on what some called “a technicality” city leaders were still concerned about the appearance of blocking a public vote on an issue that clearly now could not be settled without triggering a voter backlash.

“At the end of the day we knew we had to show the public that we’re listening because they spoke very loud and clear about the project,” Taylor said.

So in early August, the council voted to put the streetcar project on the May ballot.

“I don’t know what Council was thinking,” said Brockhouse. The May ballot will include races for all 10 City Council seats and the mayor’s office. Since Taylor has promised not to run, it’s likely to be a mayoral free-for-all. Voters will also decide on whether to give council members a significant raise.

“Add in the streetcar,” Brockhouse said “Those two contentious items on the ballot would attract fiscal conservatives in droves.”

Brockhouse sees a political opportunity for him and his cause. If he can rally his supporters in May, including the 27,000 petition signers, he thinks it’s a chance to clean house.

“Streetcar was about the frustration that the citizens of San Antonio have about their City Hall. They don’t listen and they are not accountable,” said Rodriguez. He said the city’s conservatives are now looking for candidates to run in May that will tap into that frustration. “We are going to capitalize on that,” he said.

Brockhouse said he is strongly considering running again for Council in May. He said would like a chance to do for all of San Antonio what he did for the streetcar and usher in an era of reduced spending and the end of major downtown legacy projects.