In ‘The Second Coming of the KKK,’ a Timely Lesson in the History of American Hate

Historian Linda Gordon isn’t shy about connecting the dots between the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the resurgence of hate groups today.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: Fed up with world affairs, Americans rejected internationalism and closed their doors to immigrants. As they got used to new communications technologies, they found themselves susceptible to believing the outright lies that national media networks fed them and they gleefully consumed. Demagogues whipped up white people’s race resentments and status anxieties and rode them to electoral victories. Hate groups thrived like never before.

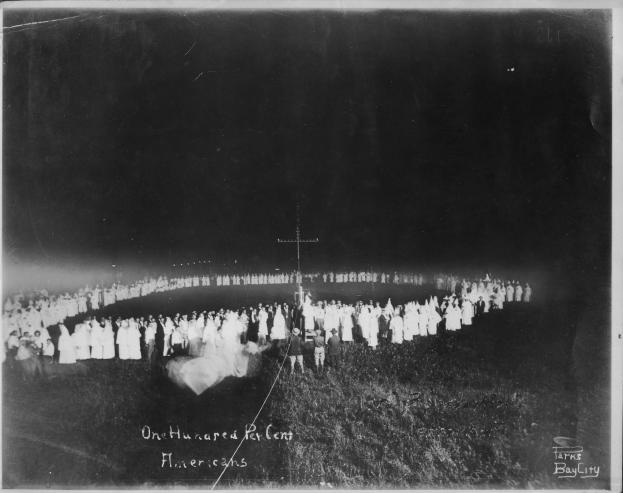

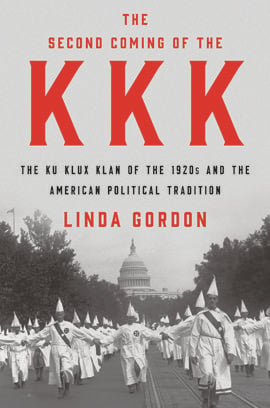

The decade was the 1920s, and the most popular of the hate groups was a rehash of the original Ku Klux Klan. Former Confederates formed the first Klan in the South during Reconstruction explicitly to terrorize would-be black voters. They were successful for a time, but white Americans outside the South rejected the KKK’s murderous tactics. Congress passed new laws to protect freedmen’s civil rights and President Ulysses S. Grant’s newly formed Department of Justice enforced them aggressively, which forced the Klan to disband by the end of the 1870s. But just before the United States entered World War I, the group rose again and flourished throughout most of the 1920s. This is the period explored by historian Linda Gordon in her sharply argued new book, The Second Coming of the KKK. Gordon makes no pretense of neutrality, and she encourages readers to draw bold lines between the political milieu of the Second Klan and our current predicament.

At its height, the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan had more than a million dues-paying members. It dominated politics throughout the United States — it was even stronger in the Pacific Northwest and Midwest than the South — and millions of Americans shared the Second Klan’s ideas about the supremacy of the white race.

The Second Klan used violence to maintain racial segregation and assert white supremacy, but on a much smaller scale compared to the first. Members of the Second Klan feared and hated African Americans, but they distinguished themselves further from the original KKK by making enemies of Jewish merchants, Greek bakers, South Asian laborers, Italian immigrants, Mormons, Catholics, bootleggers, jazz fans and flappers, among others. Gordon finds that the Second Klan drew as much from the American traditions of nativism, temperance, fraternalism, hucksterism, Christian evangelicalism and right-wing populism as it did from racism, and it used modern public relations techniques to great effect.

Whereas former Confederate officers and other southern conservative elites led the first Klan, the second drew mainly from the middle classes and organized most successfully outside of the South. The KKK of the 1920s was stronger in Oregon and Indiana than it was in Mississippi and South Carolina and more popular in cities than in the countryside. Perhaps most importantly, while public opinion turned fairly quickly against the first Klan and the federal government prosecuted its members during Reconstruction, the Klan of the 1920s was for a few years utterly mainstream. Leaders of both political parties endorsed Klan principles and in many cases openly accepted their support.

by Linda Gordon

LIVERIGHT

$27.95; 288 pages

This Klan was also a force in Texas. National leader — excuse me, Imperial Wizard — Hiram Evans, a Dallas dentist, began his Klan career by leading a 1921 attack on a black bellhop at Dallas’ Adolphus Hotel who had been accused of “improper relations with a white woman.” (Sheriff Dan Harston declined to prosecute the perpetrators. He too was a member of Dallas’s Klavern No. 66.) Big D was Klan Kountry in that decade. When Sarah T. Hughes, later a powerful Democrat and federal judge, moved to Dallas in 1922, she estimated that every single elected official in the county was a member of the Klan. Klans organized within the Democratic party throughout the state and helped elect mayors, judges, state legislators and even U.S. Senator Earle Bradford Mayfield to office.

The Dallas Klan won support from the most respected pastors in the city and continued to grow without opposition until a Dallas Morning News editorialist struck back, calling the KKK “the exemplars of lawlessness” and a “threat to personal and religious freedom. The Klan responded with fake news and a power play. After launching a whisper campaign that the DMN was run by Catholics loyal only to the pope, the KKK encouraged a boycott of the newspaper’s advertisers that nearly put it out of business.

The Second KKK, Gordon argues, influenced the national conversation in ways that still resonate. “The Klannish spirit — fearful, angry, gullible to falsehoods, in thrall to demagogic leaders and abusive language, hostile to science and intellectuals, committed to the dream that everyone can be a success in business if they only try — lives on,” she concludes.

Does it ever, and Gordon is not shy about connecting the dots. Describing Americans of the 1920s and the politics they made, Gordon deploys presentist terms such as “fake news,” “dog whistle,” and “social media.” I found each of the uses acceptable in context, but the cumulative effect may strike some readers as jarring.

Given these historical echoes, it’s worth looking at why the Second Klan dissipated when it did and what lessons its downfall holds for us. Gordon argues that the KKK was in many ways a victim of its own success. Thirty states passed racist eugenics laws and Congress passed the most sweeping immigration restrictions in U.S. history in direct response to Klan pressure. Mainstream politicians at all levels of government wrote the Klan’s ideas about racial hierarchy into law. Its most enduring achievement, Gordon concludes, “may have been its influence on political consciousness: its redefinition of Americanness, and thereby of un-Americanism, would continue to influence the country’s political culture.”

Had an astounding set of sex scandals and financial frauds not brought down the Second Klan’s leadership in the late 1920s, it is entirely possible that the organization would have remained a force into the Great Depression, when its brand of right-wing populism might well have curdled into a homegrown version of European-style fascism. Gordon’s conclusion is nevertheless mildly optimistic: In the 1920s a majority of Americans may have agreed with the Klan’s values and the assumptions behind white supremacy, but over the past century pluralist ideals have been ascendant. “[T]oday’s right-wing populists, even as they can win elections, face majorities who reject their values,” she writes.

We can certainly hope so, but we should also make it as close to impossible as we can for them to win elections. That will take something similar to the combination of a journalistic crusade, a critical mass of citizens willing to stand up for multicultural values, and the good luck that brought down the Second Klan in the 1920s.