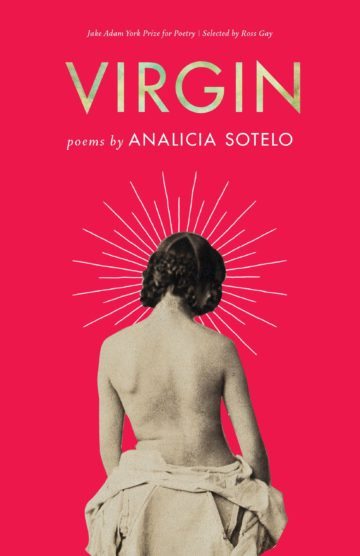

Houston Poet Analicia Sotelo’s Debut Smashes Latino Stereotypes

Sotelo’s incisive and descriptive poems take readers across Texas to interracial weddings, modern cities, dinner parties and mother-daughter conversations.

Above: Analicia Sotelo

Larry McMurtry once concluded that nearly all of Texas literature was minor and sentimentalist. Writers like J. Frank Dobie and Walter Prescott Webb mourned a Texas that had been dead for nearly half a century by the time they published their paeans to the open plains, cattle drives and an untamed nature. For most of the male authors that dominate the state’s literary canon, including John Graves and McMurtry himself, the defining features and forces of Texas’ past have been masculine. “The frontier was not feminine, it was masculine,” was McMurtry’s explanation for why men were so often the central characters in Texas fiction. But something changed by the 1950s and 1960s: Texas had become urban. “The Metropolis which has now engulfed [the state] is feminine…” McMurtry concluded somewhat begrudgingly. In his view, women and cities had unalterably changed the character of the state and the characters of its fiction, and not necessarily for the better.

Contemporary poet Analicia Sotelo has a response for McMurtry and his ilk: “The virgins are here to prove a point. / The virgins are here to tell you to fuck off. / The virgins are certain there’s a circle of hell / dedicated to that fear you’ll never find anyone else.”

Milkweed Editions

112 pages; $16

Sotelo’s first collection of poetry, Virgin, is the poetry of a Texas already transformed, free of masculine brooding. The Houston poet, who grew up in Laredo and San Antonio, is challenging deeply seated tropes. In her Texas, there are no lonesome cowboys, no barren landscapes where men break their bodies. Instead, her incisive and descriptive poems take readers to interracial weddings, modern cities, dinner parties and mother-daughter conversations. Sotelo also explores the ways that women — mothers, girlfriends and others — bear the weight of assuaging men’s insecurities. In “Death Wish,” she lists all the people entrapped in assuring a man he is adequate. She writes, “after his mother called via FaceTime / and his therapist via Skype, and he was hopeful, / and I was hopeful, and we were late to every party / because he was bleeding, bleeding from / his head to his hands, / like Christ without clear cause.”

Sotelo pushes against Chicano tropes as well. Her Texas is far from Aztlán, the mythical Aztec homeland that male Chicano civil rights artists and poets used to imagine themselves as proud warrior princes, indigenous to the land and inferior to no one. Nor is it the Nepantla of second-wave Chicana feminists, a Nahuatl word for “place in the middle.” Both concepts provided an alternative homeland to brown bodies in an indigenous past, while Sotelo places her poetry firmly in the present. Sotelo’s Texas is one of cities, but not barrios. Brown-skinned Latinos are present, but are not just workers. They are college graduates, both at home and out of place in middle-class white America. She describes her hip young professional peers, writing “I will see you on the floodwaters in your restored pine boat, looking hard / for your Foucault, your baseball caps, / your grandmother’s velvet couch…” In her world, Latinos can name-check French social theorists and allude to Greek mythology, making themselves into Ariadne but still finding themselves lost in a labyrinth, as the section of the book titled “Myth” suggests.

In Sotelo’s world, Latinos can name-check French social theorists and allude to Greek mythology.

Sotelo as a narrator calls herself a “South Texas Persephone,” a woman who lives in two worlds. Her writing explores interracial relationships to show how those worlds intersect. In the poem “Trauma with White Agnostic Male,” Sotelo describes the scene meeting her date at San Antonio’s citywide Fiesta celebration: “Meet me there: the King William District, Fiesta. / I’ll wear strawberry ribbons in my unkempt hair. / You’ll mock a trio of mariachis, / a cer-vay-sa in your spidery hand. / That’s how you’ll say it: Sir Vésa / for love of my tender Latina outrage.” She is left wondering whether his taunts were meant to be flirtatious or insulting. How could someone living in Texas and San Antonio be so conspicuously out of touch with Latino culture?

She returns to this theme in “My English Victorian Dating Troubles.” There, the distance between men and women, as well as between white people and Latinos, is evident in the anachronistic and geographically distant title of the poem. She asks:

Why does the twenty-first century feel like this?

Like men are talking into

their favorite phonograph

& the phonograph is me

receiving their baritone: You’re so exotic

Watch out, men, says my violin

I am a Royal Bengal man-eating tiger

I will devour your pith helmets

as well as these enchiladas

piled high with American mozzarella any time of day

See, there is a white man

in every single one of us.

Men’s desires are for a past era, phonographs in a time of smartphones. They still see themselves as conquerors, but their pith helmets are a sad costume of two centuries past. And Latinos are still considered exotic as Bengal tigers, though they comprise nearly 40 percent of the state’s population. Yet all is not bleak. Men and women, Latinos and whites share similar appetites. They are still drawn to each other (four in 10 interracial marriages in the United States are between whites and Latinos) and they are both drawn to a Tex-Mex cuisine that is a combination of two worlds — enchiladas with American mozzarella.

Virgin is the poetry of a purple Texas, a confused metaphor for a color palette that is meant to indicate the browning of Texas, the growth of cities and the increasing visibility and centrality of women. This smart and timely collection shows that we are in many ways already living in that world transformed, with all its promises and problems.