Despite Progress, Texas Leads in Uninsured Hispanic Kids

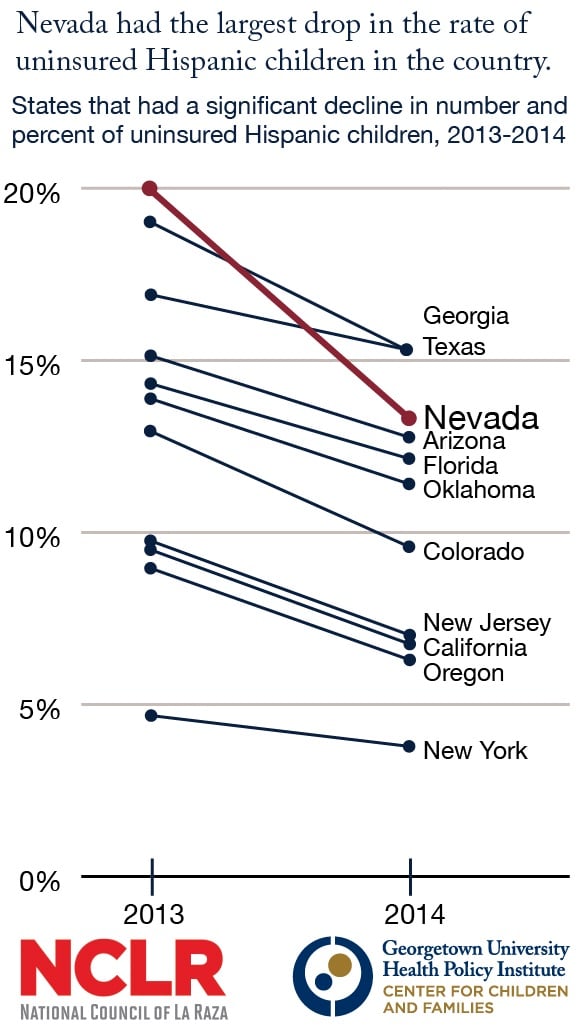

Above: The number of uninsured Hispanic children in Texas is dropping after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, but the state is still tied with Georgia for the highest rate of uninsured Hispanic kids in the nation.

More Hispanic children in Texas obtained health insurance coverage in 2014, but the state still has the highest rate of uninsured Hispanic kids in the country, according to research released Friday. More than a half-million Hispanic children remain uninsured, though that number is dropping.

The report, co-authored by the National Council of La Raza (NCLR) and the Center for Children and Families (CCF) at Georgetown University, found that nearly 53,000 previously uninsured Hispanic children in Texas got coverage from 2013 to 2014, the first full year the Affordable Care Act was in effect. That’s an almost 9 percent decline in uninsured Hispanic kids, down to 533,000 from 585,000.

However, Texas’ rate of uninsured Hispanic children is the highest in the country at 15.3 percent, tied with Georgia. The national rate is 9.7 percent.

Laura Guerra Cardus, associate director of the child advocacy group Children’s Defense Fund-Texas, called the Texas decline in uninsurance “impressive,” but also said the state has a long way to go.

“We still have a lot of work to do in Texas,” she said.

The national rate of uninsured Hispanic children dropped from 11.5 percent in 2013 to 9.7 percent in 2014, an “historic low,” according to the report. Researchers attribute the decline to the Affordable Care Act’s so-called “welcome mat effect” — as more uninsured adults obtain health insurance through the ACA, they also enroll their children in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

“With nearly one-third of the child population projected to be Latino by mid-century, we know the future well-being and success of our nation is linked to that of the Latino community,” Steven T. Lopez, manager of health policy at the NCLR, said in a press release. “We are pleased to see that the gap in health coverage between Hispanic children and all children is closing but there are still inequities to address.”

But despite the change, Hispanic children still make up the largest share of uninsured children in the United States overall. According to the report, in 2013, two thirds of uninsured Hispanic children were eligible for the Medicaid or CHIP programs but hadn’t enrolled.

For the last 20 years, the rate of uninsured children, including Hispanic children, has steadily decreased thanks to Medicaid and CHIP, which together cover 3.4 million children in Texas, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Still, Hispanic kids make up 30 percent of all remaining uninsured children in Texas, the NLCR-CCF report found.

Guerra Cardus said obstacles such as language barriers and complex, bureaucratic eligibility rules often keep parents from signing their kids up for Medicaid or CHIP. She also said immigrant families worry about how and whether enrolling their kids in public health insurance programs will expose their undocumented relatives.

“We know that when we get parents enrolled, their children are more likely to get enrolled, stay enrolled and get the care they need to healthy.”

In Texas, uninsured children qualify for the Medicaid or CHIP programs if they live at 200 percent of the federal poverty level. In a family of four, that translates to an income of roughly $44,000 a year. The state requires families to renew their Medicaid or CHIP enrollment every six months, and the waiting period for CHIP coverage to kick in can last up to three months, all of which Guerra Cardus said make it hard for kids to have continuous health coverage.

“Many of these families are applying, but they’re having a hard time staying enrolled,” Guerra Cardus said. “Part of what Texas needs to do is to align [its] rules and modernize them to coincide with the ACA, instead of keeping [rules] that are known barriers.”

According to the report, of the 20 states with uninsurance rates for Hispanic children below the national average, 17 had expanded Medicaid. But Texas officials have strongly and repeatedly rejected the Medicaid expansion, leaving nearly 1 million poor adults, many of whom are parents, without an option for health insurance. Guerra Cardus said closing this so-called coverage gap would also result in more children being covered.

“We know that when we get parents enrolled, their children are more likely to get enrolled, stay enrolled and get the care they need to healthy,” Guerra Cardus said.