Photos of Dystopia

FotoFest, Houston’s biennial art photography fair, bears witness to a planet in peril.

A version of this story ran in the March 2016 issue.

Above: Edward Burtynsky’s photo, “Rock of Ages #7,” was taken at the E.L. Smith Quarry in Barre, Vermont, in 1991.

There’s a moment halfway through Manufactured Landscapes, a 2006 documentary about Edward Burtynsky, when the celebrated Canadian photographer tries to talk his way into an industrial site in Tianjin, China. The smog outside lies thick and foreboding; the media flack seems to sense that it will cast the company in a negative light. “It’s very dirty,” she tells Burtynsky. “I don’t think it’s a good day to make beautiful pictures.” Burtynsky’s translator tries to convince her: “But through his camera lens, through his eyes, it will appear beautiful.”

Spend enough time at “Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet” — opening this month in Houston as part of the biennial art photography fair FotoFest 2016 — and you’re bound to wonder if the flack was right. Isn’t it a bit wrongheaded to seek beauty, as Burtynsky and other artists on display do, in the wounds we’ve inflicted on the natural world — rising water and global temperatures, species on the edge of extinction, our own toxic trash destined to outlive us? What do we make of this instinct to create beautiful pictures about a world gone wrong through humanity’s action? Is it effete sentimentality in the face of challenges that demand a more serious approach? A canny activist’s vehicle to draw us in before bumming us out with the unpleasant truth? Disaster porn?

“Changing Circumstances,” which features at least 30 photographers, many of them world-renowned, does not offer a one-size-fits-all philosophy of art-making in the Anthropocene; the artists are too diverse in style and approach. They range from a National Geographic-affiliated pioneer of underwater shark photography (David Doubilet) to a conceptual artist who has tried to register the Earth’s atmosphere as a UNESCO World Heritage Site (Amy Balkin) and a pair of still-life diorama makers who build empty-calorie landscapes out of Froot Loops and processed meats (Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman). If there is a unifying vision behind the exhibition, it belongs to the curators: FotoFest co-founders Wendy Watriss and Fred Baldwin, and the festival’s new executive director Steven Evans.

According to Watriss, the curatorial team tried to look beyond the images and peer deeper into each artist’s narrative of engagement, research and response. The beauty, perhaps, comes in that last step, as a unique human being decides what sort of vision of the land he or she is going to take forth into a threatened future.

“One of the important things we want to have happen at this biennial is have people not only see a litany of the challenges facing us, but also how individual people, talented people, people who think, have been affected by their own close association with the larger view of nature and how we live,” Watriss says. “It’s not an academic approach to the issue. It’s very personal. They’ve come up with surprisingly diverse ways, many of them very beautiful, of looking at the planet.”

Take Burtynsky, for example. He grew up in an area of great natural beauty, just miles from Niagara Falls. He naturally gravitated toward formal landscape photography, taking after predecessors such as Carleton Watkins, famous for his mammoth-plate visions of Yosemite Valley. But, Watriss says, “It didn’t take [Burtynsky] long to see that this sort of aesthetic exploration of landscape, of frontier photographers who were also essentially trying to sell settlers on developing the land, was no longer relevant.” Soon, Burtynsky shifted his focus to the human impact on the land.

Stylistically, he continued to develop all the grandiose trappings of a formal master of landscape photography. His images convey a genius for symmetry, composition, color and light, all products of an almost inhuman perfectionism and patience with his unwieldy large-format camera. Burtynsky’s translator did not lie to the Chinese media flack: Whatever he casts his eye on, from electronic-waste dumps to open-pit mines to dried-up river deltas, manages to register as beautiful. His picture of the port of Tianjin, with undulating hills of coal stretching off to the horizon through smog that looks like morning mist, is no exception.

Whatever Burtynsky casts his eye on, from electronic-waste dumps to open-pit mines to dried-up river deltas, manages to register as beautiful.

“These days, we’re very used to looking at aerial photography, but he was one of the first to use visual expression from an aerial standpoint in a targeted way that treads very carefully, I think, between aesthetic and formalist concerns, and content,” Watriss says.

Watriss knows from experience how deep engagement of a subject can change an artist’s way of seeing. Raised in cosmopolitan San Francisco, Greece and Spain, she had a career as a journalist, including a jaunt to Eastern Europe to cover the Prague Spring, before joining forces with Baldwin in the early 1970s. The two embarked on a documentary expedition through the Deep South, hauling a 13-foot trailer behind their Mercedes as they made their way from Georgia to Texas, snapping photos all the way. But after reaching what they thought would be the end of their road, they decided to shelve their touristy “back roads of the South” project and instead delve deeply into Texas, which became their life work.

Watriss and Baldwin spent two years living with a poor black family in Grimes County, near Navasota, another two years with a poor white family in Gillespie County, near Fredericksburg, and additional months in a Mexican-American border community. Their goal was an integrated anthropology of rural American life, linking race and class to culture and landscape, all based on research, oral history and close observation of family life in a few tiny communities. “Fred and I had been photojournalists all over the world before we came to rediscover our own roots as North Americans,” Watriss says. “We came to Texas and we discovered that it really is a microcosm of America.”

Their appreciation of the relationship between complex large-scale issues and their photogenic manifestations in local communities became a guiding principle of FotoFest, which Watriss and Baldwin founded in Houston in 1983. “It definitely affects the viewpoint we took to FotoFest from the start, which I think is still operative — that is, the interconnection between the local and the global,” Watriss says. “That interconnection is parallel with human interconnection with the rest of the planet.”

As far as local microcosms go, it’s hard to imagine a city more relevant to the question of our planet’s future than Houston. More than just a coastal industrial center in an environmentally stressed area of the United States, Houston is also a one-word synecdoche for the American fossil fuel industry. Companies such as Exxon Mobil Corp. are increasingly implicated in funding and promulgating fake climate science that directly contradicts their own internal climate models used for drilling plans in the Arctic, as Scientific American pointed out in an article last fall. More than any other industry, the energy sector favors Republicans with its political donations; perhaps as a result, Republicans remain, in President Obama’s words, “the only major party… in the advanced world that effectively denies climate change.”

Nor is it possible to light a match at a Houston art world event without igniting a trail of oil money. FotoFest is no exception. Its top-listed funder in 2014, the Brown Foundation, is a fortune built on the founding shares in Brown & Root, now Kellogg Brown & Root (KBR), long a subsidiary of Halliburton. This Houston-based enterprise has built everything from Central Texas dams to Guantanamo Bay prison blocks, from Nigerian oil installations to toxic waste “burn pits” on U.S. military bases in Iraq. (The Brown Foundation has been independent of Brown & Root and KBR for many decades, making honorable charitable expenditures primarily in the arts and education.)

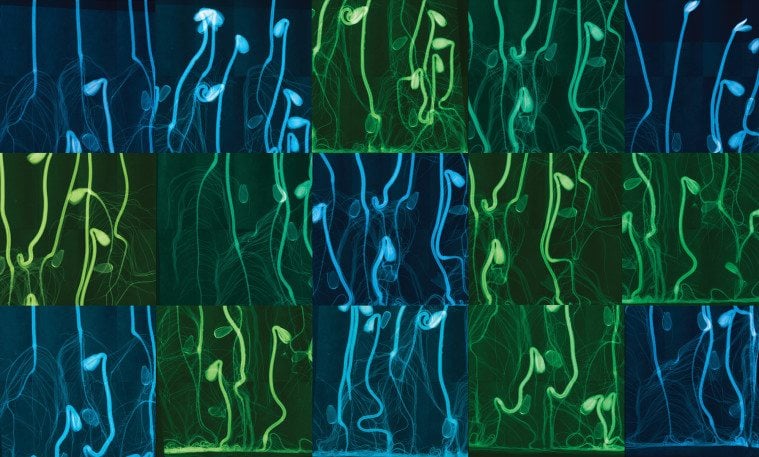

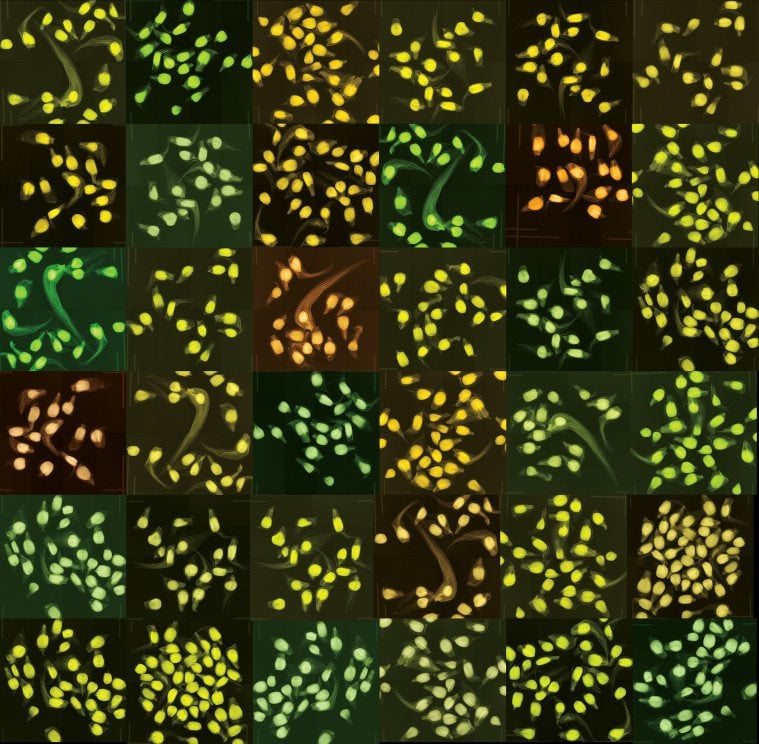

“Archiving Eden.” Courtesy of Dornith Doherty, Moody Gallery, Houston; and Holly Johnson Gallery, Dallas

FotoFest has maintained a long-term interest in the environment, with previous exhibits titled “The Global Environment” (1994), “Water” (2004), and “The Earth” (2006). But more than any past festival, this year’s exhibition looks toward the future and the serious environmental threat generated by unregulated industry and the carbon economy. Viewers may be tempted to see “Changing Circumstances” as a reflection on the curators’ long engagement with Houston and the delicate problem of making and displaying activist art for the city’s oil-and-gas-linked audiences and collectors.

Watriss stresses, however, that she had no intention of calling out key local climate offenders. “I have come to the conclusion that there are economic forces within the industrial complex dealing with energy that are much more effective than art can be in terms of changing things,” she says. “The economics of natural gas, solar energy, wind and other renewables, along with general public opinion and governmental policy, are beginning to slowly do that. … In terms of talking to the head of Exxon or Conoco or other such companies, I don’t know how useful that is. Ultimately, I’m not sure that that kind of discussion works or is effective.”

Isn’t it a bit wrongheaded to seek beauty, as Burtynsky and other artists on display do, in the wounds we’ve inflicted on the natural world — rising water and global temperatures, species on the edge of extinction, our own toxic trash destined to outlive us?

“We’re speaking to Houston, but we’re speaking to Houston on a different level,” Evans says. “We’re speaking to the citizens of Houston, who are incredibly sophisticated and coming from all over the world. The challenges that Houston will face in coming years are similar to other coastal cities.”

Watriss draws hope from the recent climate treaty out of Paris, particularly statements reflecting the role of public opinion in forcing world leaders to reach the accord. “That’s what all these artists in their statements are pleading for, that we all as individuals become concerned,” Watriss says. “It sounds so trite, but it does have an effect eventually. Policy alone is not going to do it. Comments that have come out of Paris have indicated that those public voices, collectively, have made a change.”

Taking in “Changing Circumstances,” even viewers who don’t share Watriss’ optimism will be moved by the artists’ depth of engagement and innovative thinking. Several have adeptly transformed collective grief about our ecological situation into beautiful displays of public mourning. India’s Atul Bhalla, for instance, makes images that link rising oceans with religious rituals of submersion. Uruguay’s Roberto Fernández Ibáñez transforms charts of escalating global CO2 levels into serene mountain ranges. Their work registers as a prayer for serenity as the wages of climate change come due.

“We’re speaking to the citizens of Houston, who are incredibly sophisticated and coming from all over the world. The challenges that Houston will face in coming years are similar to other coastal cities.”

Dornith Doherty, the lone Texan on the FotoFest 2016 roster, is another artist exhibiting guarded faith in the future. Her featured project, “Archiving Eden,” is the result of a years-long investigation into seed banks — massive underground vaults that protect cryogenically frozen germs of many of the world’s plant species from complete extinction due to climate change, habitat loss and Monsanto-style monoculture.

One half of Doherty’s photos are documentary-style impressions of the seed bank installations, which are off-limits to civilians and often far off the beaten path. The images convey a hope in the mammoth scale of 21st century technology: If we can preserve heritage cereal species in a high-tech ark, surely science can someday provide solutions to other ecological challenges.

The other half of her photos are more meditative and abstract. Exchanging her camera for the high-resolution X-ray machines used by seed bank scientists, she creates impressionistic renderings of the seeds themselves. Her results are beautiful and strange. “The X-ray technology allows you to peer into these tiny plantlets, some of which are only the size of a grain of sand,” Doherty explains. “It allows you to see what you wouldn’t be able to see without aided vision. That mirrors what seed banks are trying to do. Time and life in suspended animation is very much on my mind as I’m working.”

Doherty’s presence at the festival also reflects its significance as a place of exchange and inspiration for politically and ecologically committed art photographers. Like several generations of Houston artists, she developed in the festival’s nurturing shadow. She volunteered at the inaugural 1986 FotoFest; more recently, she’s sent her students at the University of North Texas in Denton to view festival offerings. “I certainly hope I’m contributing to the conversation,” she says. “I’m looking at really specific ideas about stewardship, not only in the archiving community. The thing I’ve encountered working on this is the fact that individual actions matter, individuals coming together in networks.”

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.