‘Everything Is Gone’: Family-Planning Clinics Disappear From Rural Texas

A version of this story ran in the March 2013 issue.

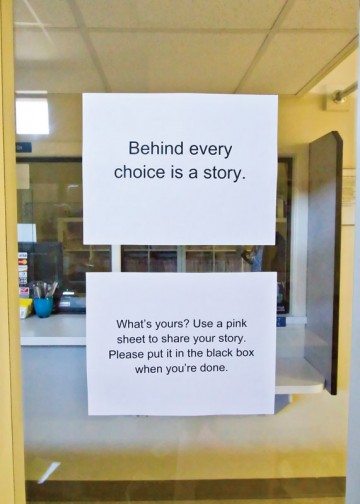

Above: The main room of the Hill Country Community Action Agency’s San Saba family-planning clinic now sits empty, except for a single rose hanging from the window blinds. The card on the rose reads, “Without mothers, nobody would be here!”

The day Melody Ball heard she’d soon be out of a job, she noticed the plant in her office had begun to wilt. Ball was director of family-planning services in the small Central Texas town of San Saba, helping to oversee four women’s health clinics in the region, all of which would soon close due to state budget cuts.

The day Melody Ball heard she’d soon be out of a job, she noticed the plant in her office had begun to wilt. Ball was director of family-planning services in the small Central Texas town of San Saba, helping to oversee four women’s health clinics in the region, all of which would soon close due to state budget cuts.

The peace lily, with its delicate white flowers, had flourished in her office for years, and Ball was sad to see it begin to struggle in summer 2012. In the weeks that followed, as Ball considered what to do with her surplus pregnancy tests and contraceptives, she kept a watchful eye on the plant. She tended it carefully while she supervised the clinic closures. Even as workers rolled exam-room equipment into moving vans, she hoped the plant would revive. On the day that her agency’s last well-woman clinic closed for good, the peace lily finally withered and died, and Ball resigned herself to its demise. “I guess we’ll carry it out at the end of July and throw it in the trash.”

When Ball’s office closed for good at the end of July 2012, it was the end of a longstanding family-planning program for women in San Saba and nine surrounding counties. For 30 years the agency responsible for the program, Hill Country Community Action, had relied on state grants to provide free or steeply discounted contraceptives to more than 2,000 low-income clients annually. These services had been provided at six family-planning clinics serving 12,000 square miles of Central Texas. Last summer, after months of financial uncertainty for family-planning providers across Texas, the state health department informed Hill Country Community Action that the agency would no longer receive its annual $394,000 from the state. The news was devastating.

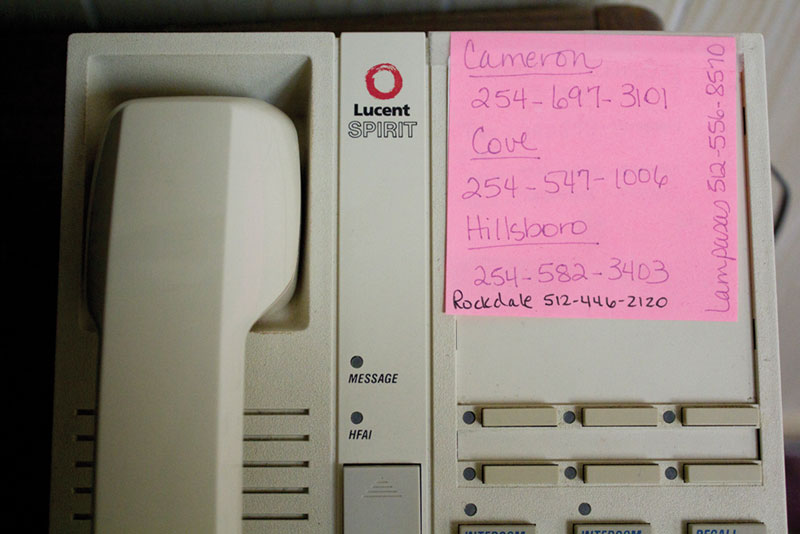

During the 2011 session of the Texas Legislature, politicians had slashed the state’s family-planning budget by two-thirds. The remaining money was doled out based on a restrictive funding formula that state officials designed specifically to deny Planned Parenthood money. But in a surprise move, the formula also defunded family-planning clinics—like those run by Hill Country Community Action—that had no connection to Planned Parenthood. Family- planning providers waited months to learn whether the state would continue to fund them. Ball’s agency limped along on a three-month financial extension, causing the agency to close clinics in Lampasas and Rockdale in a bid to keep its other four clinics open and financially stable. The lancing blow came in May 2012, when Hill Country Community Action learned that it had permanently lost most of its funding from the state. In a further affront, the decision came so late that Ball had only six weeks to shutter operations. Now she had to swiftly close her remaining clinics in San Saba, Hillsboro, Cameron and Copperas Cove.

Last summer I made the two-hour trip from Austin to visit Ball and her colleagues in their scenic corner of the Texas Hill Country. As I drove through San Saba County’s rugged, rolling country with its glinting rivers, I could see why the region attracts hunters and anglers from across the state. Farmers produce millions of pounds of pecans here every year. Ranchers raise livestock on rich earth. Sandstone hewn from San Saba quarries can be found in swimming pools and country clubs across Texas. Yet the laborers who power the local economy are poor. According to a 2009 report commissioned by the city of San Saba, an estimated 34 percent of households live on an annual income of $25,000 or less, just above the federal poverty level. More than half of San Saba residents work in blue collar, farm or service jobs. In fact, Ball told me that many of these low-wage earners—pecan shellers, quarry workers and service staff—had frequently relied on the family-planning services provided by Hill Country Community Action. Only 3 percent of her clients can afford to pay full fee, Ball told me. Now that the Legislature had defunded them, San Saba’s family-planning specialists had to take away affordable reproductive services from Central Texas’ working poor. In a reversal of what they’d trained to do, they removed cancer screenings, STD tests, pregnancy tests and birth control for 2,000 men and women per year.

Hill Country Community Action wasn’t the only provider to suffer. The cuts to the state’s family-planning budget wreaked widespread damage on women’s health care in Texas. By summer 2012, a survey conducted by the Women’s Health and Family Planning Association of Texas for The Texas Observer found that more than 60 family-planning clinics had closed statewide. By late fall 2012, the Texas Department of State Health Services estimated that the number of people receiving family-planning services would be reduced by 138,000. Public-health experts were alarmed. The Texas Women’s Healthcare Coalition—composed of 33 nonpartisan organizations—recently formed to advocate for restoration of family-planning funding. “Lack of access to contraception means more unplanned pregnancies, higher risks of child abuse and neglect, higher Medicaid costs, and, unfortunately, more abortions,” the alliance’s position statement notes.

The impact will most likely hit hardest in rural areas, where low-income women had fewer options to begin with and will now have farther to travel for care. In San Saba, as Melody Ball closed her clinics one by one, she redirected displaced clients to Lone Star Circle of Care in Round Rock, to a Planned Parenthood clinic in Waco—both about a one- to two-hour drive each way—or to nearby private providers charging full fees. Working mothers were sent to health centers at least an hour’s drive away, teens to private doctors who dispense contraception only with parental consent. When I asked where the pecan shellers, quarry workers and undocumented laborers would go, Ball simply shook her head. As the clinics closed last summer, some clients didn’t yet know that they’d lost access to health care. By the time they realized, it would be too late. The staff would be gone, the files shredded and anything of value donated elsewhere: pharmaceuticals to Planned Parenthood, disposable drapes to the Boys and Girls Club, 12,000 condoms to United Way. “This is a sad day for Texas,” said Tama Shaw, executive director of Hill Country Community Action, as she stood in front of a calendar ink-stained from months of clinic schedules. Now it showed only one entry—Ball’s birthday in July.

I arrived at Hill Country Community Action’s family-planning headquarters in the city of San Saba (pop: 3,099) last July, just days after the final clinic had closed. Ball and Shaw greeted me alongside nurse manager Gina Woodward. Later, Eva McDuff, the billings officer, staggered into the room carrying a box of files headed for the shredder. We sat on cozy sofas in their reception area. They were countryfriendly and keen to talk.

“The pendulum swung back and forth for years,” said Shaw, a striking woman of 64 whose dry demeanor suggested that she’d seen it all and then some. Shaw, a San Saba native, explained the intricacies of family-planning funding. Her clinics relied on funds from the Women’s Health Program—then a largely federal program run through Medicaid but since taken over by the state so Texas officials could bar Planned Parenthood—as well as family-planning grants, comprising both state and federal dollars, from the Texas Department of State Health Services. The size of the latter pot had always fluctuated according to legislative whim, Shaw said, adding, “I never thought the pendulum would fall.”

Yet fall it did. After months of financial uncertainty following the 2011 legislative session, the effects were finally felt in San Saba. Not only did Hill Country Community Action lose nearly $400,000 in grants, but also the discounted pharmaceutical pricing that came with it. The agency still received Medicaid Women’s Health Program funds but, given that many of their clients were undocumented and therefore ineligible, the family-planning clinics couldn’t afford to stay open. “I tried to write a budget for just two clinics,” Shaw said, “but without the discounted pharmaceuticals, we’d just be writing prescriptions that no one would be able to fill. We couldn’t afford it. That state grant had been the glue that held it together.”

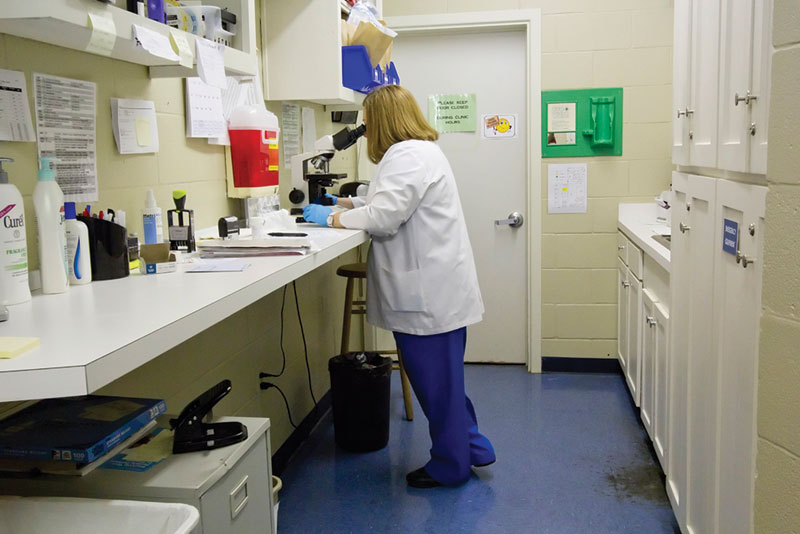

For $394,000 a year, a small community-run program like the one in San Saba had operated efficiently. The costs had been minimal because the small staff did everything itself. Staffers had counseled clients, dispensed prescriptions, performed health exams, registered women for benefits, run financial models, submitted paperwork to the state, and then cleaned the office when they were done. “If you wanted bang for your buck,” said Shaw, “this was it.” The women who worked at San Saba’s family-planning enterprise were deeply invested in their work. The family photos dotting the walls and Woodward’s stethoscope slung over a portrait of George Strait suggested that I could have been in one of their homes. And in many ways, this office had felt like home to them. Shaw had been at the agency for 35 years, Ball for 19, and McDuff, the newest employee, arrived in 1997. I commented that compared to the large community health centers that had absorbed most of the diminished state budget, this family-planning clinic seemed like a mom-and-pop shop. They agreed. “You can go into any small rural community,” Ball said, “and find that doctors have joined forces with the Scott & Whites and the Setons to survive. But we were still mom-and-pop, and that’s why our clients loved us. We gave them something that was private and intimate and relationship-based. Sometimes they’d just come in to vent.”

This rapport seems especially valuable when providing birth control, one of the most private aspects of health care. It’s especially so in conservative towns where religion and politics collide, and where talking about sex can be tricky. Hill Country Community Action had once fought to get sex educators into the schools, and Woodward noted that many of her teen clients were sexually active before even coming to see her. San Saba Independent School District promotes an abstinence-only sex-education program, which meant that, given the dearth of realistic information available, Woodward was often the only barrier between teenagers and unplanned pregnancies. Woodward was genial and plainspoken, making me want to tell her all my secrets. I suspect that many of her clients had done so.

As I prepared to leave San Saba, I found Ball in her office, packing a box with photos of her six grandchildren. She gave me a sheaf of papers from her desk listing the procedures performed by her clinics in the previous nine months. All were now unavailable: 1,500 pregnancy tests, 118 syphilis tests, 744 pap smears, 618 Depo Provera injections, 514 annual medical exams… As I flipped through the papers, I heard McDuff on the phone, calmly referring former clients to clinics in other regions. When I left, each of my hosts was on a different line, helping women they had served for years find somewhere else to go.

Now, seven months later, the clinics remain closed. Shaw, who still runs other programs at Hill Country Community Action, recently told me that only 110 clients have called the agency for directions to other providers. The receptionist refers patients to Round Rock or Waco. When I called those providers, I was surprised to find that they could offer me next-day appointments. Though 98 percent of Hill Country Community Action’s clients had received well-woman care for free, this is not the case at other clinics. No longer able to participate in the Women’s Health Program for political reasons, Planned Parenthood in Waco must now charge patients for care. A well-woman exam, for example, costs $99. Women’s Health Program clients can be seen for free in San Saba at a local Scott & White provider, but that clinic charges full-fee to those who don’t qualify: women under 18 or over 44 or who can’t prove that they are legal citizens. An office visit at the Scott & White clinic would cost $83. Similarly, Lone Star Circle of Care in Round Rock provides services on a sliding fee scale based on income. None of their services are free.

It was more difficult to track where other displaced clients had gone. A Scott & White staffer told me by phone that she hadn’t seen an increase in new patients since Hill Country Community Action closed its clinics. Similarly Lone Star Circle of Care, via an email from director of communications Rebekah Haynes, said that the number of patients the Round Rock clinic had seen from San Saba was relatively small. The Planned Parenthood health center in Waco had seen a significant uptick. Danielle Wells, assistant director of communications for Planned Parenthood of Greater Texas, said by email that in 2012, the Waco health center had served 10 to 15 times as many patients from the zip codes once served by Hill Country Community Action as the year before. Clearly, some displaced patients have found new providers, but others haven’t. Time will tell what effect the closures will have on the reproductive health of those others, but public-health policy analysts are expecting an increase in unintended pregnancies and the number of births covered by Medicaid.

Texas’ new family-planning infrastructure is in flux. The Texas Legislature has three months left in its 83rd regular session, and advocates are lobbying for lawmakers to restore money while public-health specialists are scrambling to study the impact of the state’s defunding of family-planning clinics. In San Saba, even if funding is restored, it would be difficult to reopen the clinics. The staff has mostly moved on to other jobs. Gina Woodward now works for her family business, having hung up her stethoscope for good. After months at home, Melody Ball started a job in another field this month. Eva McDuff is still without work. I asked Tama Shaw if she might revive the family-planning program if funds are restored from the state or federal government. “It would take too much startup money, because the facilities are gone,” Shaw said. “We couldn’t start up again. Everything is gone.”