Faking the Grade: The Nasty Truth Behind Lorenzo Garcia’s Miracle School Turnaround in El Paso

Lorenzo Garcia boosted test scores by banishing low-scoring students. We may never know how many he lost.

A version of this story ran in the November 2012 issue.

Five years ago, back when she still trusted El Paso’s public schools, Linda Romero Hernandez got surprising news from her youngest daughter: Bowie High School would not allow her back next year.

Romero and her two older daughters had all graduated from Bowie, the historic school just across the street from the Rio Grande—with Ciudad Juarez beyond it—that has anchored Southside El Paso for generations. Bowie’s history is rich and proud, entwined with the story of the segundo barrio, where so many immigrants have started their lives as Americans. But in 2007, Bowie’s future was in doubt. The school had posted consistently low scores on TAKS, the standardized test that determined its federal rating. Bowie faced a drastic shake-up, maybe even closure. Pressure to boost performance was intense, so even though Romero’s daughter wasn’t a troublemaker, her test scores made her a liability. “This isn’t about grades. This is about TAKS,” Romero recalls an administrator telling her.

Romero couldn’t believe it. She worked at Bowie, as a drop-out prevention counselor. She was a longtime Southside activist, too, and she vowed to fight the administration’s decision. “It’s your right to go to school,” she told her daughter.

“But these people don’t want me there,” her daughter said.

She wasn’t the only one. More than a dozen of her friends had been told to find a new school, and she ticked off their names.

She told her mom there was no point in fighting. Instead of pursuing a transfer, Romero’s daughter opted to drop out. Then she got pregnant. Around the same time, Bowie cut Romero’s job, along with programs for students with limited English-speaking skills. Romero took a job at a charter school in northwest El Paso, where she found dozens of students trying to enroll, saying they’d been turned away from their neighborhood schools—not just Bowie, but El Paso High and Austin High as well.

Romero was surprised, but somewhat relieved, to find that the issue was bigger than just her daughter. “It comforts me, in a greedy way that I hate,” Romero says. “It’s not that I feel good, but at least my daughter’s not the only one, you know?”

Romero was getting an early glimpse of one of the nastiest test-rigging schemes in U.S. history. Bigger scandals in other cities have involved falsified student test scores, but what happened in the El Paso Independent School District from 2006 to 2011 under its superintendent Lorenzo Garcia was far more foul: kids who scored too low were simply shown the door. They got jobs, got pregnant, maybe got their GED online or moved to Mexico. Test scores shot up. Other districts asked how administrators did it, and El Paso administrators were glad to take credit.

It was a remarkably effective strategy. The district has since tried to pass it off as the work of a rogue superintendent, which it is, but it’s more than that. Current district officials now talk about the need to move on, to rebuild trust, but many of them are the same people Garcia relied on to implement his plan.

More important, the testing regime that drove Garcia’s end-run is still driving El Paso ISD and every other American public school. Garcia’s scheme was an extreme consequence of a system that prizes test scores above all, that rewards and punishes entire districts based on a sliver of education that’s easy to measure. States cut corners to make their scores look good all the time, by setting an incredibly low bar for “passing” a test, or just making the test easier. Garcia violated the law, but in manipulating the system, he was simply following that system to its logical, ugly conclusion.

By May 2009, El Paso ISD’s miraculous turnaround was well underway. Bowie had been on the brink of state intervention for years, but it was suddenly turning in solid test results. The El Paso Times noted that Bowie principal Jesus Chavez cried when he told his students the state had rated Bowie “recognized,” the second-best distinction. “The kids felt the urgency, the staff felt the urgency, the district felt the urgency,” Chavez told the paper.

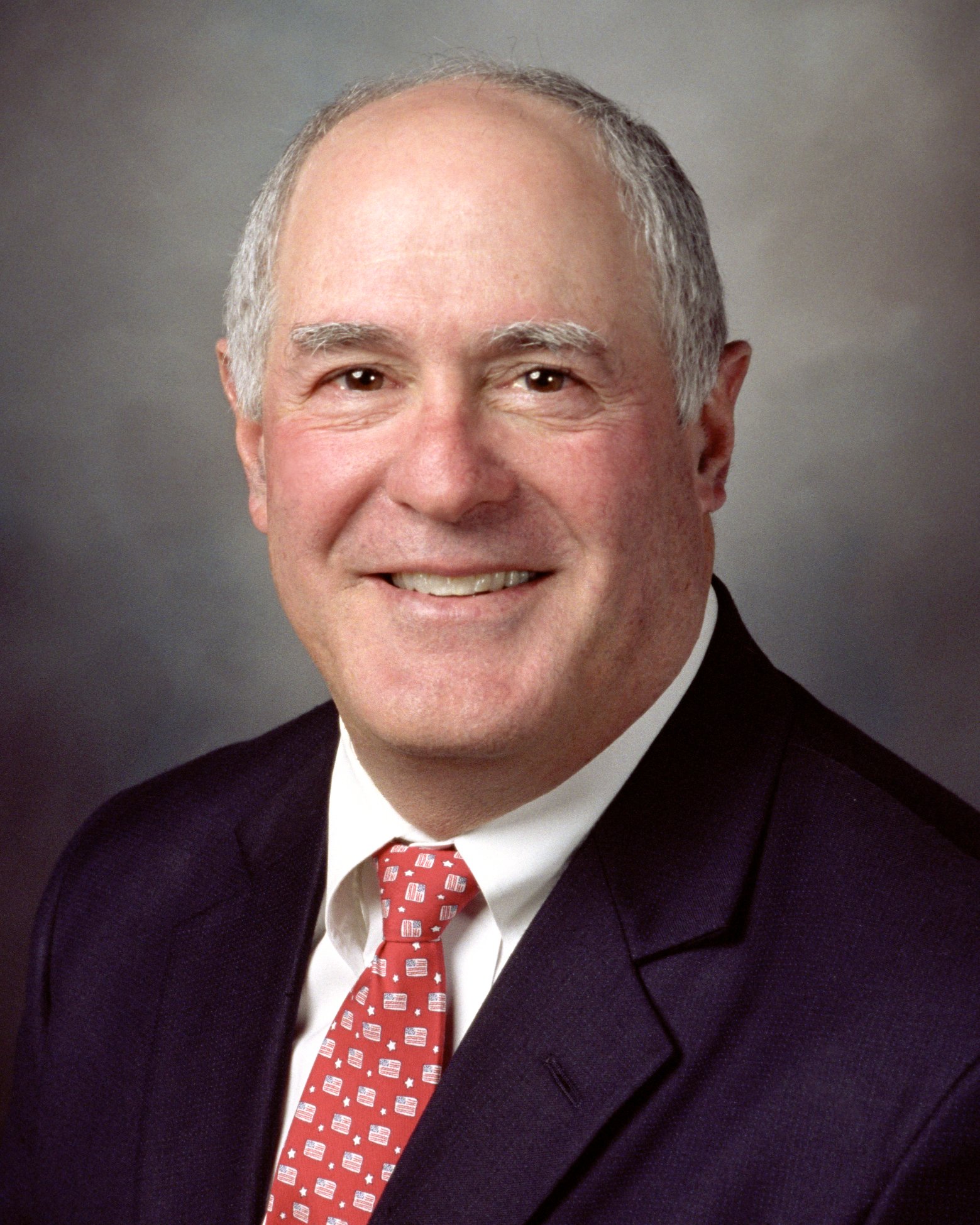

Dan Wever, who’d been a school board trustee during the rough years before the turnaround, went to the Texas Education Agency’s website to try to figure out how the district had done it.

Wever is a tall man with a contagious guffaw. Numbers make him laugh. “I love Excel,” he says. “When I can sort 600,000 numbers in a second and a half, that just tickles the hell out of me.” After a 30-year career with AT&T, Wever has retired to a life spent sifting through El Paso’s public spending records in search of connections: a city software deal steered to an old boss, maybe, or a contract that never went out for bid. When he finds something juicy, he posts his discovery online.

Three years ago, Wever was looking at Bowie’s enrollment statistics when he saw something strange: a 2007 freshman class with 381 students numbered just 168 by the end of its sophomore year. “This drop from the previous year’s numbers is much larger than in years past,” he wrote on an online message board. “This could not possibly happen, could it?”

Federal standards rate entire schools on the basis of tests taken by sophomores. It was only a hunch, but Wever sensed something funny about Bowie’s mysterious shrinking student body. Enrollment plummets, scores shoot up—one way or another, it looked like someone was tinkering with the stats. Days later, Wever posted again: “This has been gnawing on me for the past week,” he wrote. “Is it ‘okay’ because EPISD and Bowie get a boost, or is it ‘not okay’ because there is no way that the scores can be sustained in the future, and no way that the improvement can be as dramatic as it was?”

He sent his suspicions to the state education agency, then to the U.S. Department of Education, but couldn’t get anyone interested in investigating. After a group meeting about an unrelated issue with El Paso’s then-state Sen. Eliot Shapleigh, Wever stuck around to describe what he’d found. Shapleigh had already begun hearing from parents like Linda Romero about forced transfers and student dismissals at Bowie. Wever’s data gave him numbers to back the anecdotes. Shapleigh started gathering parents’ stories, and his staff confirmed Wever’s research.

Wever kept poking around. He found a steady climb in the number of tests Bowie administrators labeled “exempt,” meaning they wouldn’t be counted in the school’s rating. Wever’s wife, Frances, a teacher’s union president at the time, noticed administrators getting pay raises and bonuses tied to test performance. The Wevers received anonymous phone calls from people who said the district was up to something.

Wever told Shapleigh about a computer program called INOVA that the district had purchased after Garcia was hired. Given students’ practice test scores, INOVA predicted the likelihood of each student passing the TAKS. The software was sold to the district ostensibly as a diagnostic tool, to help identify students who, say, needed more help with math. Wever knew that INOVA could just as easily be used to tag students likely to bring the school’s test scores down. He’d voted against buying the program when he was on the board.

Bowie teachers told Shapleigh how students who should’ve been sophomores were held back, or rushed ahead to their junior year. School ratings are also tied to graduation rates, and teachers said they were pressured to give students credit even if they refused to do their work. Students were rushed through “mini-mesters”—special courses Garcia created that would give students full course credit after one two-hour weekend class or a research paper. Younger teachers taught those sessions for extra pay, and were sent around the district to train other schools in the “Bowie model.”

“We took the general complaints that were coming in and started laying them on the table,” Shapleigh says. “By November, December of 2009, I was fairly sure what we had … I had a sense of the scope. I knew it was not just at Bowie, I knew it was not only immigrant kids.” Still, 2009 was a time of terrible violence in Juarez that drove thousands into El Paso seeking safety. Shapleigh says he was sickened by the thought that the district, under Garcia, was casting its neediest students out to keep its numbers up. With a flair for the dramatic, Shapleigh took to calling these students los desaparecidos—“the disappeared”—as if they’d been taken in the night by some dictator’s goon squad.

Romero walked door to door with Shapleigh’s secretary in South El Paso and found even more students who’d been told to leave Bowie. A volunteer force grew as parents of newly dismissed students joined in. At one community meeting at a South El Paso skate park, Romero says, she spotted a district employee driving slowly by, taking pictures of the crowd. “Everybody was scared,” Romero says. “Nobody wanted to speak up.”

Some of the kids said they were doing fine without high school, taking online GED courses or working. Some were ashamed; if they’d tested better, they could have stayed in school. The students had been given an array of justifications for their banishment. Some had been told they’d been absent too often to stay in school, and that it would cost hundreds of dollars to fight such truancy decisions in court; others said they’d been photographed crossing the bridge from Juarez as proof they lived outside the district. One boy said his principal threatened to report his aunt to immigration if he didn’t leave school.

Under Garcia, Romero says, the district exploited fear of the courts, fear of Border Patrol and the community’s trust in the school. “Our parents are very submissive to schools and authorities,” she says. “These students were made to feel like they did something wrong.” She says some parents acquiesced when their kids were asked not to return, and they didn’t think Romero should be questioning the school’s apparent success. School officials knew they’d be able to manipulate the community, she says. “But they never thought that people were watching them.”

Shapleigh confronted Lorenzo Garcia with his findings in January 2010. In a room at his Senate office in El Paso, Shapleigh gathered a few of his staffers, two school board members and a handful of Bowie graduates. Shapleigh passed around handouts showing the sophomore enrollment drop Dan Wever had spotted, and a list of ways Shapleigh said Garcia had gamed the system: siccing truancy officers on low-scoring students, holding students back to repeat as freshmen, or skipping them ahead to their junior year. Whatever it took to keep struggling students from taking the 10th grade test.

When the accusations were done, Garcia stood. His lawyers did not reply to interview requests for this story, but others who were in the room recall his reaction: His face was red, his hands were shaking. They say he cried as his anger peaked. “‘How dare you,’” Shapleigh recalls Garcia saying. “‘How dare you accuse me, and how dare you hurt these students. I myself am an immigrant, and I grew up picking cotton, and if there’s anyone in this district who knows what these kids go through, it’s me. Senator, you have no place hurting these kids like that.’”

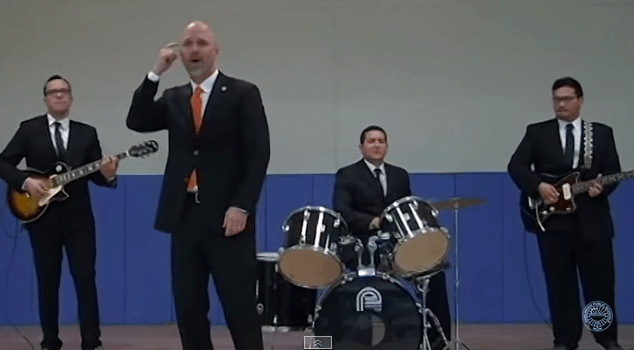

The superintendent fought back with a rally at Shapleigh’s alma mater, Coronado High School in West El Paso, where a sea of students and teachers surrounded Garcia with signs: “Don’t diminish my success,” and “We support Dr. Garcia!”

Garcia began his career as a teacher with Spring Branch ISD, in western Houston. He served as assistant superintendent in Dallas, then superintendent back in Spring Branch. He moved to El Paso ISD in February 2006 and began cultivating a loyal and well-paid entourage of top administrators and principals. Between 2004 and 2008, administrator salaries rose 43.5 percent in El Paso ISD, compared to 9.4 percent statewide. Over the course of his tenure, Garcia earned $54,000 in performance bonuses, and his top lieutenants collectively got bonuses of nearly $50,000 for the 2008-2009 school year.

In his 2010 State of the District speech, Garcia offered a defense of Bowie’s gains: “It’s not by accident that the test scores are up. It’s by design.”

After Shapleigh made his allegations public, Garcia began cashing in favors to polish his image. An El Paso ISD board meeting hosted State Board of Education member Charlie Garza’s inauguration, during which Garza apologized for Shapleigh’s meddling. He called the allegations “a black cloud over the remarkable advancement that the teachers and students in the El Paso Independent School District are making.” State education officials investigated at Shapleigh’s request and cleared the district of wrongdoing. The El Paso Times ran a softball Q&A with Bowie principal Jesus Chavez about how nice it felt to be vindicated.

Garcia was a rising star thanks to the district’s high scores and spoke openly about his ambition to become state education commissioner. Romero and other parents kept tracking down kids, and TV news reports sometimes covered their plight, but Garcia seemed to have the city’s faith. “A lot of people were brainwashed,” Romero says.

Shapleigh, who retired from the Senate in 2010, spent his last weeks in office delivering evidence of Garcia’s scheme to elected officials around El Paso. He pleaded with the U.S. Department of Education to investigate. He asked President Obama to step in and prevent the spread of this “perverse strain of No Child Left Behind.”

The evidence that led to Garcia’s downfall was filed away in a drawer at district headquarters. In October 2009, Bowie counselor Patricia Scott had alleged that credits had been removed from the transcripts of 77 Bowie students to keep them from becoming sophomores. Most of these students, Scott said, possessed limited proficiency in English, and so would probably do poorly on state tests. Her complaint, along with Shapleigh’s, generated an internal audit.

Management of internal audits was among the responsibilities the school board had turned over to the superintendent when Garcia was hired. The audit, which confirmed that dozens of transcripts had been changed but failed to identify any coordinated wrongdoing, had been delivered directly to Garcia in early 2011.

The audit hadn’t yet been made public, but it had caught the attention of the FBI. Local reporters began circling Garcia as rumors of a federal investigation spread.

Susan Crews, a counselor with the district, remembers the line of men—“black suits, white shirts and black ties,” she recalls—that filed into a district counselors’ meeting in August 2011. One asked where they could find Lorenzo Garcia. Someone pointed down the hall and, just like that, the agents hauled Garcia away. He faced charges of mail fraud and wire fraud, not only for sending phony test scores to the state, but also for a half-million-dollar contract for classroom posters steered to Garcia’s former mistress in Houston. He pleaded guilty in June to two counts of fraud, and in October he was sentenced to three and a half years in federal prison.

Once Garcia was arrested, El Paso Times reporter Zahira Torres began turning out front-page story after front-page story peeling back the layers of the scandal. Former principals who didn’t play along with Garcia’s scheme said they had been coaxed into early retirement and replaced by Garcia allies. Former students told of being forced out of school, and teachers spoke of the toxic environment the “Bowie model” created in the classroom. As former Bowie English teacher Patricia Padilla recalls today, “Garcia turned the students against us.”

When Atlanta schools were caught cheating on state tests last year, Georgia’s governor appointed a task force to investigate, and eventually fired 178 implicated administrators and teachers. Shapleigh is irate that’s not happening now in El Paso. “You’re not seeing the kinds of bold, decisive actions that need to take place to fix this. What happens now?”

Figuring out how many students were involved would take a case-by-case review of student files, Shapleigh says. At Bowie alone, one class lost 214 students in 2008—a 55 percent loss, about twice the usual dropout rate. Garcia’s “priority schools division” included 21 other district schools, all targeted for dramatic turnaround strategies copied from Bowie. At Garcia’s sentencing, the judge suggested that more than 250 students were affected by the scheme. Shapleigh says the number could be in the thousands.

Six “unindicted co-conspirators” are mentioned in the federal indictment against Garcia, and the FBI investigation is ongoing. Jesus Chavez, the former Bowie principal who ran the school during its miracle turnaround, still has a job at the El Paso district office. In 2010, he was given an official reprimand for changing students’ grades, and was reassigned to the district’s business services department. Today, Chavez says Garcia threw him under the bus to keep the district office looking clean. Chavez got a $6,000 raise the same year he was reprimanded. His assistant principal, Johnnie Vega, still has his job. Both have said they cooperated with the FBI. Damon Murphy, who ran the priority schools division Garcia created to transform struggling campuses like Bowie, is now superintendent at Canutillo ISD outside El Paso. He has denied playing a role in the scandal, blaming principals he’s called “lackadaisical.” After Garcia’s arrest, his former chief of staff Terri Jordan stepped in as interim superintendent, a position she held just long enough to call a press conference at which she fingered Murphy for his complicity. She has since returned to her post as chief of staff, while two interim superintendents have stepped through the revolving door of district leadership since Garcia’s arrest.

Other administrators have come forward to tell reporters they helped Garcia only out of fear. Patricia Scott, the counselor who reported grade-changing to her bosses early on, says that’s a weak defense. “The way they want to resolve things is to say, well, I was given a directive,” Scott says. “Yeah, you were given a directive, but you’re also an adult person with a choice.”

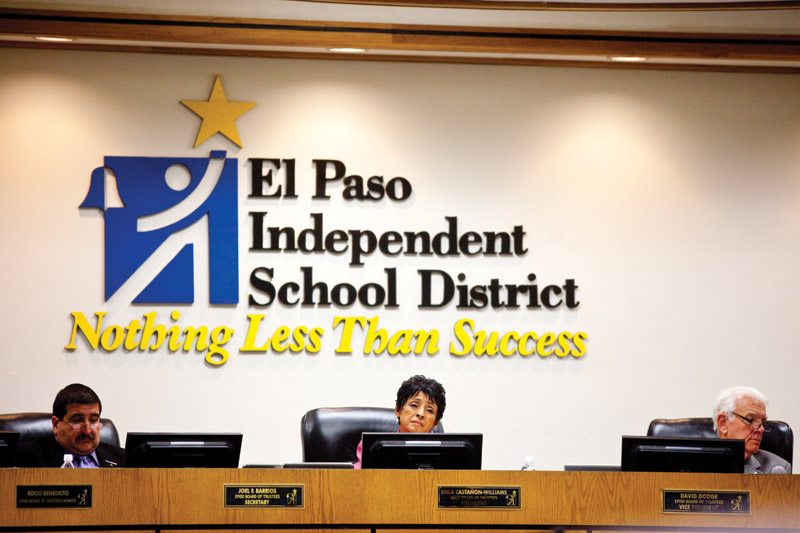

Most of the talk in the district today is about moving on. At weekly school board meetings, teachers and administrators pour words of sympathy into the official record, cooing to trustees about how hard the backlash has been, how difficult their jobs must be. Garcia came to the district heralded as the man who could save El Paso’s schools from closure, and was given a long leash to run the district as he saw fit. He tangled that leash into a mess trustees never could have imagined.

“They’re shell-shocked. You always get the sense that they’re under siege and they don’t know what to do,” says City Council member Susie Byrd. She says the El Paso ISD board gave Garcia far too much control, and now they’re not interested in investigating what happened. Along with Shapleigh, and Dan and Frances Wever, Byrd has helped form a group called Reform EPISD Now, which has circulated a petition calling for the entire EPISD board to step down. “Watching them bungle through the last several months, I just think, man, you guys are not prepared for this,” Byrd says.

The board has hired an independent firm to audit its schools and assess the damage. Board president Isela Castañon-Williams says that trustees never had the resources to investigate what was going on, and that even the state couldn’t investigate as thoroughly as the FBI did. “This board of trustees is committed to getting to the bottom of what happened,” she says, but the trustees are also being careful not to upset the FBI’s work by dismissing high-ranking administrators. “To take action at this point would result in interfering in their investigation.”

The Texas Education Agency has placed El Paso ISD on probation—one step away from losing state accreditation—and assigned a monitor to help the district fix itself and hire a new superintendent. During a visit to El Paso in October, new Texas Education Commissioner Michael Williams told the El Paso Times that the district had a limited window—he wouldn’t say how long—in which to fire folks who helped Garcia carry out his plan before TEA cracks down further.

Shapleigh blames TEA as much as anyone for turning its back on his complaints years ago, and doubts the agency’s interest in exposing the depths of a scandal that unfolded on its watch. He says the district’s plan to hire an auditor is too little, too late. “Both TEA and EPISD are quite comfortable with each day the statute of limitations runs on what they did to each of these students,” Shapleigh says.

The feds may have nabbed Garcia for mail fraud charges, but Shapleigh reckons the plan violated a slew of federal and state laws as well. Students who were kicked out of school because of limited English skills can either file a complaint with the Department of Education or take their old schools to court, says Jorge Ruiz de Velasco, director of the University of California at Berkeley’s Earl Warren Institute on Law and Social Policy. “Because the discrimination was intentional, that gives their parents the legal right to go directly to court,” he says. “They can go after the principals directly.”

The district continues to face tough federal accountability standards. In September, an administrator told state monitor Judy Castleberry that El Paso ISD is “dissolving from the inside out.” Byrd says that parents at Reform EPISD rallies are now questioning not just the Garcia scandal, but the test-heavy approach to public education that motivated it. “They’re really angry about the district, and they’re really angry about Garcia,” she says. “But they’re really worried about the test.”

Today, Romero lives in a house next door to her childhood home on the Southside, one of five generations of her family under the same roof. Her daughter who was forced out of Bowie lives there as well, and talks about getting her GED someday, though she’s had three kids since she left high school, and taking care of them claims most of her energy.

If she had stayed at Bowie, she might have gone on to college. Maybe she would have ended up just where she is today. There’s no telling for sure. Each of the kids touched by Garcia’s scheme—the ones held back, the ones skipped ahead, and the ones who just disappeared—lost something distinct and unknowable.

It’s not the details of who knew what, or when, that Romero wonders about today. It’s not the numbers. It’s those kids. It’s the heartlessness of what Garcia did, and that so many went along with him.

“I’ve completed the puzzle, and I can see clearly what the picture is,” Romero says. “But I don’t understand.”