Exiled Mexican Seeking Asylum Pedals for Justice

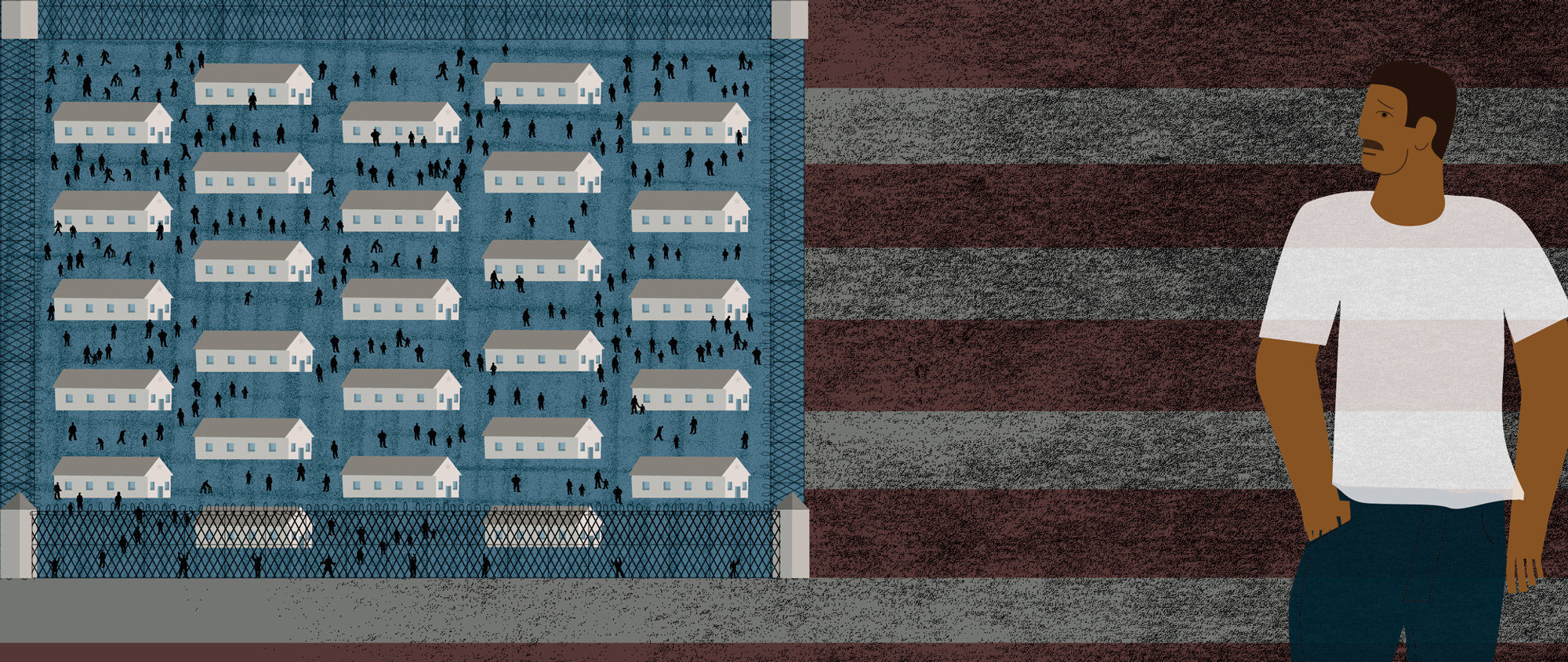

Above: Carlos Gutierrez arrives in Austin after traveling 12 days and 701 miles from El Paso on his Pedaling for Justice campaign.

Carlos Gutierrez rolled into Austin Saturday after a 701-mile bicycle ride from El Paso. Austin was the final destination on his 12-day ride across Texas to raise awareness about Mexican asylum seekers.

News cameras crowded around an exhausted and emotional Gutierrez as he carefully stepped off his bike and looked around, searching the crowd for his father’s face. For the next few minutes, family members and supporters took turns hugging the 35-year old cyclist.

Just two years ago a ride like this would have been unthinkable. A successful businessman in Chihuahua, Gutierrez was targeted by cartel members who demanded monthly extortion payments of $10,000. When Gutierrez could no longer pay, cartel members cut off his feet and left him to die as an example to other business owners.

Miraculously, Gutierrez survived. But to save his life his legs had to be amputated below the knees. Afterward, Gutierrez and his family fled Mexico to seek asylum in the United States. His asylum was neither granted nor denied. Instead, it was “administratively closed,” so that Gutierrez, while able to work, is in a sort of limbo until his case is reopened.

Typically, less than two percent of Mexican asylum cases are granted each year. Last year 9,206 Mexicans applied for political asylum in the U.S., and only 126 received asylum, according to U.S. Justice Department data. Carlos Spector, the El Paso immigration attorney who is representing Gutierrez, says the reason so few cases are approved is political. If the U.S. starts granting asylum to Mexicans, he says, it would be admitting that violence really does exist in Mexico and that the war on drugs has failed.

In exile in the United States, Gutierrez was struggling to adjust to life in a wheelchair. Then one day he met Eddie Zepeda, a prosthetic specialist, who pledged to help Gutierrez walk again with the help of prosthetic legs. Zepeda provided all of his services free of charge. Gutierrez refers to Zepeda as his guardian angel.

Gutierrez has come a long way since then, training for months to ride across Texas and raise awareness about the violence and impunity destroying the fabric of Mexican society. To bring attention to his situation and that of thousands of other Mexicans fleeing violence and seeking asylum here, he embarked on his Pedaling for Justice campaign in late October.

“I’m not here to point the finger at anyone; simply to alert the government as to what’s going on with the Mexican people,” Gutierrez said. “People from other countries are granted asylum as soon as they touch American soil, but not us Mexicans. Because even with the circumstances we’ve lived through – in my case the attempt on my life – it isn’t enough to get asylum. I don’t think it’s fair that it’s this way for Mexicans just because we are from a neighboring country.”

The war on drugs that started in 2006 has claimed thousands of Mexican lives and has forced thousands more to flee their homes. But Mexicans continue to be denied asylum because judges argue they are not fleeing political persecution, but are tortured, kidnapped or threatened in their home country only for economic gain. Thus, it isn’t the state that’s persecuting victims, but common criminals. Gutierrez’s lawyer Carlos Spector disagrees.

“Asylum law doesn’t reflect the Mexican reality, which is that much of the extortion is possible because of the relationship with the state. ‘Authorized crime’ really reflects reality much more than the concept of ‘organized crime.’ Organized crime implies that there are bad criminals on one side and good guys, like cops, on the other. In reality, authorized crime better describes what we’ve seen – that organized crime is not possible without the complicity of the municipal, state and federal police.”

Because the police is an extension of the state, Spector says, and because the police is often responsible for acts of violence or allows acts of violence to occur with impunity, the state is responsible for what happens to victims of organized crime. That, he says, makes it political persecution.

Spector, who started the nonprofit advocacy group Mexicanos en Exilio, or Mexicans in Exile, won the first-ever asylum case for a Mexican national in 1991. Since then, he’s been able to win political asylum for more than a dozen people, including victims of violence in the Juarez Valley and Mexican journalists who exposed organized crime.

Gutierrez joined Mexicanos en Exilio when he moved to El Paso two years ago, and later had the idea of cycling across Texas to educate U.S. lawmakers about the desperate situation so many Mexicans find themselves in in their home country. He’s trying to combat the misconception that some lawmakers have that asylum-seekers are trying to abuse the legal system in order to gain lawful status in the country.

“We’re not here because we wanted to be or because that was our inclination,” Gutierrez said. “The circumstances that led me to this country were that I had my feet mutilated. This isn’t a game, we’re not playing with the law, with justice, with the system at all – this is the reality.”

Gutierrez says he set out on this ride to help other people in the same situation he’s in. Now that his long journey is behind him, he wants to do something bigger to help more victims of drug violence, especially ones who like him have suffered a physical disability at the hands of organized crime.

“People keep asking me, ‘What’s next?’” he said at the press conference today in Austin. “Something big. It doesn’t stop here. I won’t stop until God stops me. No one else and nothing else can stop me, only God.”