‘Even the Mafia Was More Circumspect’

Glenn Shankle goes from regulator to lobbyist.

The revolving door between government and the private sector is a time-worn tradition in Texas. But here’s a case that on its bare facts is particularly egregious.

In January, six months after stepping down as the executive director of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Glenn Shankle signed on as a lobbyist for Waste Control Specialists, the company recently licensed by TCEQ to build a massive radioactive waste dump in West Texas. His lobby contract is worth between $100,000 and $150,000, according to the Texas Ethics Commission.

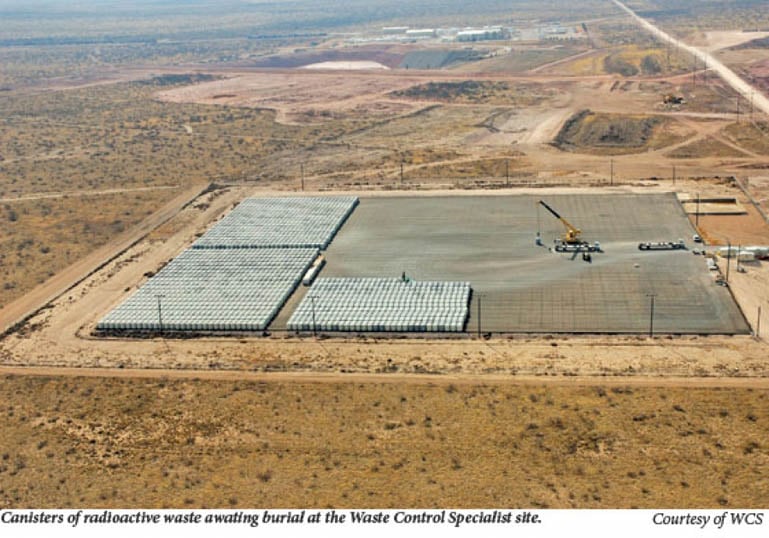

When Shankle left TCEQ in June 2008, the agency was readying, per Shankle’s orders, two licenses authorizing Waste Control to bury millions of cubic feet of radioactive waste. The four-year license review process had been one of the most time-consuming and contentious in agency history.

Shankle’s own technical staff, geologists and engineers had concluded definitively that the dump could not legally be permitted. An Aug. 14, 2007, memo drafted by two geologists and two engineers bluntly stated that the landfill’s proximity to two aquifers made it “highly likely” that radioactive waste would leak into the groundwater. The site, they wrote, “cannot be improved through special license conditions.” They recommended denying the license. With little explanation, Shankle overruled them. His only sop to the staff were license conditions requiring additional studies before construction.

Amazingly, Shankle said in a brief telephone interview yesterday—one of the few times he has ever spoken to the press—that he had never heard of any of this.

“I was not aware of that,” Shankle said of his own technical staff’s recommendations. If true, that’s stunning. According to the Houston Chronicle:

When WCS President Rodney Baltzer learned of the [August 14] memo, he immediately sought out meetings with the agency’s executive director, Glenn Shankle, who decided in December [2007] to begin drafting the license.

In fact, records from TCEQ, previously discussed in the Observer, show that during the time period after the staff’s recommendation, Shankle was frequently meeting with Waste Control officials, attorneys and lobbyists. Waste Control is owned by Harold Simmons, the Dallas billionaire and major Republican donor who helped bankroll Swift Boat ads attacking John Kerry in 2004 and television ads in 2008 linking Barack Obama to Bill Ayers.

Baltzer left nine messages for Shankle and four for [Deputy Executive Director Dan] Eden between July 2007 and January 2008, according to phone logs that reflect only missed calls. Eden met with Waste Control officials at least five times during that period. Former Republican Congressman Kent Hance, a Waste Control investor and chancellor of the Texas Tech University System, paid a visit to Shankle’s office in early November.

Cliff Johnson, a principal in Textilis Strategies, an Austin-based firm that lobbies for Waste Control, visited with Shankle in September. Shankle also met with Giblin, Baltzer, and Mike Woodward, a Waste Control lobbyist and attorney with Hance’s law firm, during that period.

The outcome of this full-court press was the Shankle-ordered drafting of the coveted disposal licenses, permits that are worth untold millions to the company. In fact, without these licenses Waste Control is a losing venture. Last year, Waste Control lost $21.5 million, according to SEC filings for Valhi, Waste Control’s parent company. In other words, Shankle had done a very big favor for Waste Control.

The move so upset his staff that three of them quit in protest. One of them, Glenn Lewis, who coordinated one of the license review teams, reacted with disgust and anger when told yesterday that Shankle was lobbying for Waste Control.

“Even the Mafia was more circumspect than this,” Lewis said. “To find out now that Mr. Shankle—who was in constant communication with WCS throughout this ordeal—now is on retainer for [WCS] is shocking in that it is so brazen and such an insult to everybody who worked on that application. It just shows that any objective appraisal by the TCEQ was from its inception a fantasy and that big money and a lot of political power won once again. … They should have just issued the license the day after it was received and saved everybody a lot of trouble.”

When it was suggested to Shankle that there was at least the appearance of a quid pro quo, he responded: “The freedom of the press can go so far. You’re making some very serious allegations.” Then he hung up.