El Paso Art Exhibit Honors Braceros’ Forgotten Legacy

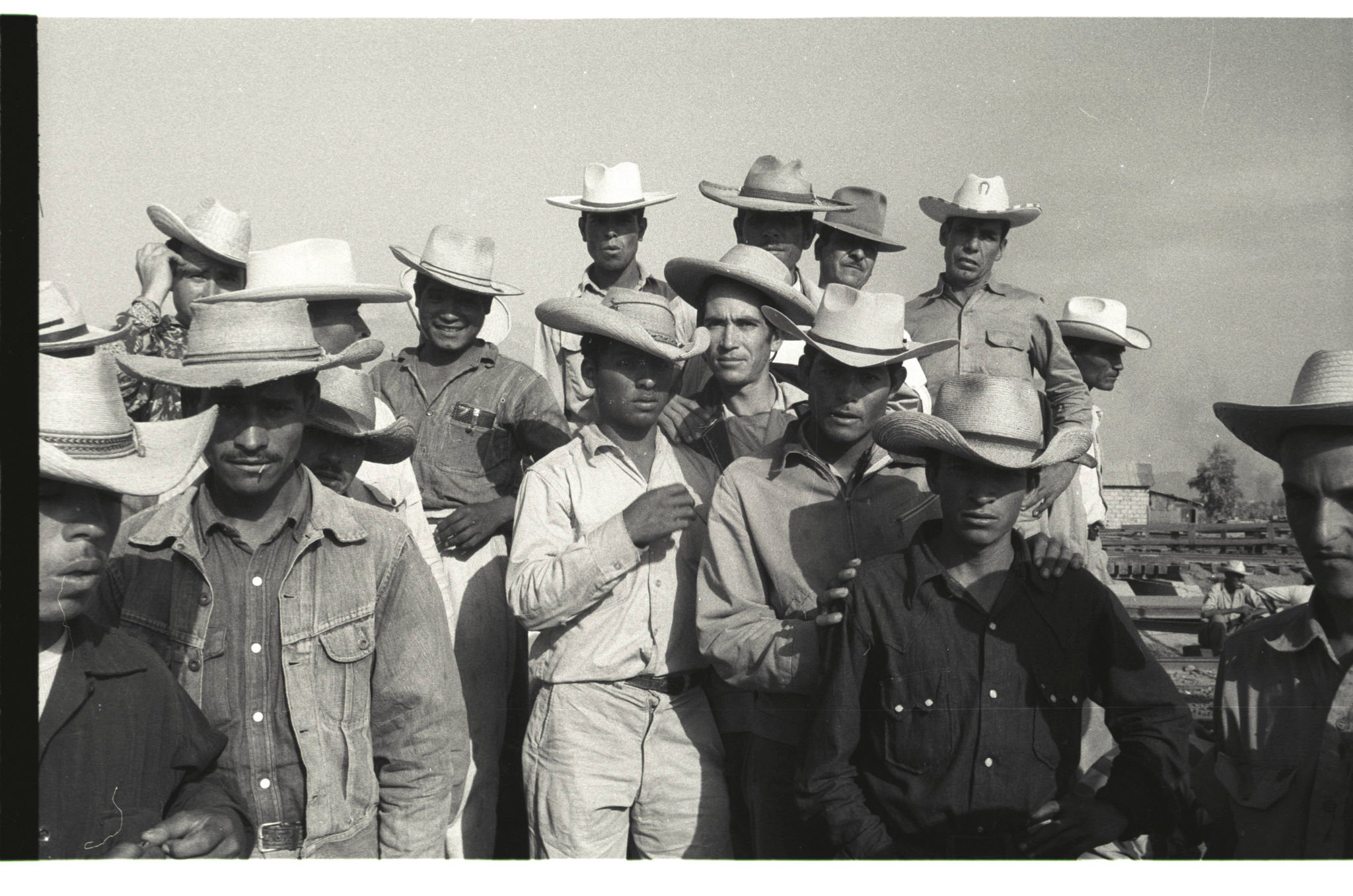

“Bracero Memories” tells the stories of some of the 4.5 million Mexican farmworkers who traveled on guest visas to the United States from 1942 to 1964.

El Paso Art Exhibit Honors Braceros’ Forgotten Legacy

“Bracero Memories” tells the stories of some of the 4.5 million Mexican farmworkers who traveled on guest visas to the United States from 1942 to 1964.

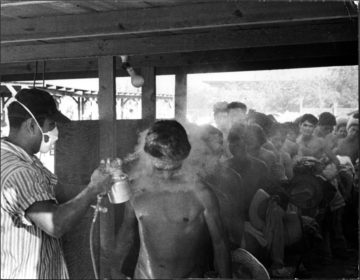

The black-and-white photo is striking, even disturbing. Dated 1956, it shows a line of a dozen or so young farmworkers waiting their turn to be sprayed with the toxic pesticide DDT. Packed into a makeshift stall, they stand shirtless, clutching their hats. The worker at the front of the line is obscured by a cloud of white vapor as another man — who wears a mask to protect himself from the fumes — aims a spray canister directly at his face. Photographer Leonard Nadel depicts his subjects as many Americans saw migrant farmworkers at the time, and arguably still do: a faceless mass, more like cattle than people.

This image is part of “Bracero Memories,” an exhibit at the University of Texas El Paso’s Centennial Museum that runs through December 16. The multimedia exhibit brings together artifacts, tools and artwork to tell the story of the braceros, more than 4.5 million Mexican farmworkers who came to the United States on guest worker visas from 1942 to 1964. The largest foreign worker program in U.S. history, it was prompted by farmers’ fears that World War II would lead to a labor shortage.

Francisco Uviña, 84, is a former bracero who left his home in Durango to pick cotton on a farm in Pecos. Uviña now lives in El Paso and toured the exhibit with his daughter, Magdalena Ronquillo. He says that seeing the artifacts brought back memories of long hours and poor working conditions.

“It would get so cold that icicles would hang from the roof all the way to the floor, but we’d still have to go out and pick,” Uviña says. “We would pick for a little bit, then put our hands in our pockets to thaw and then go back. None of us wanted to work there, but if we didn’t go, we’d get sent back to Mexico.”

Daniel Carey-Whalen, the museum’s director, says that many young visitors to the exhibit didn’t know anything about the braceros. (As the Observer reported last month, Texas public schools still lack an approved Mexican-American studies textbook, though 52 percent of the state’s public school students are Hispanic.) The fumigation photo has provoked especially strong reactions.

“Just looking at the photo, one of the kids that was visiting started crying,” Carey-Whalen says. “It’s interesting to see young people who’ve never heard of the program being touched by this history.”

Many of the challenges that braceros endured — wage theft, substandard working conditions, inadequate housing and abusive bosses — are the same as those faced by Texas’ 200,000 migrant farmworkers today. Nine in 10 Texas farmworkers still don’t have licensed housing.

“The issues that we’re dealing with today, [such as] trying to find cheap labor, that’s been going on even before the bracero program,” Carey-Whalen says. “This isn’t a new issue.”

“I wish that I had seen it in a history book. … The country needs to know what they did.”

The exhibit also contains artifacts on loan from the Border Farm Worker Center in El Paso. Instruction booklets issued by the Mexican government along with letters that braceros wrote home are on display, but the most memorable item is the short-handled hoe. Only 16 inches long, the tool required workers to crouch in the fields for hours at a time. Though the hoe was eventually outlawed in 1975, it became a lasting symbol of back-breaking labor and oppression.

Uviña was one of three former braceros who visited the exhibit and Socorro’s Rio Vista Farm this fall to for a two-day history summit timed to coincide with the program’s 75th anniversary. The farm was a kind of Ellis Island for braceros: a processing center where workers were fumigated and vaccinated, as well as waiting in between jobs. Last year, Rio Vista became the second site in Texas to receive the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s “National Treasure” designation.

“The thing that surprises me is how few people know the site exists,” says Sehila Casper, the National Trust field officer who led the effort to earn the designation. “History happened there.”

Ronquillo says her father rarely speaks about his experience as a bracero, saying only, “They didn’t treat us right.” But seeing the exhibit and walking the grounds of Rio Vista prompted an emotional conversation between father and daughter, and she was left wondering why she didn’t learn about the braceros in school.

“I wish that I had seen it in a history book,” Ronquillo says. “It would’ve made a greater impact for me, especially knowing that my dad was a part of it. The country needs to know what they did.”