How Earl Campbell Changed Football in Texas

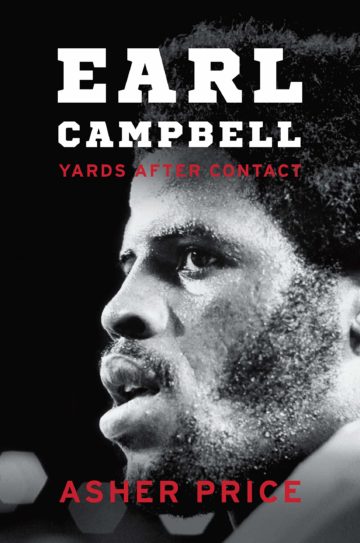

In Earl Campbell: Yards After Contact, a new biography of the famed player, Asher Price writes, “Earl Campbell tried, through carrying the football, to transcend race.”

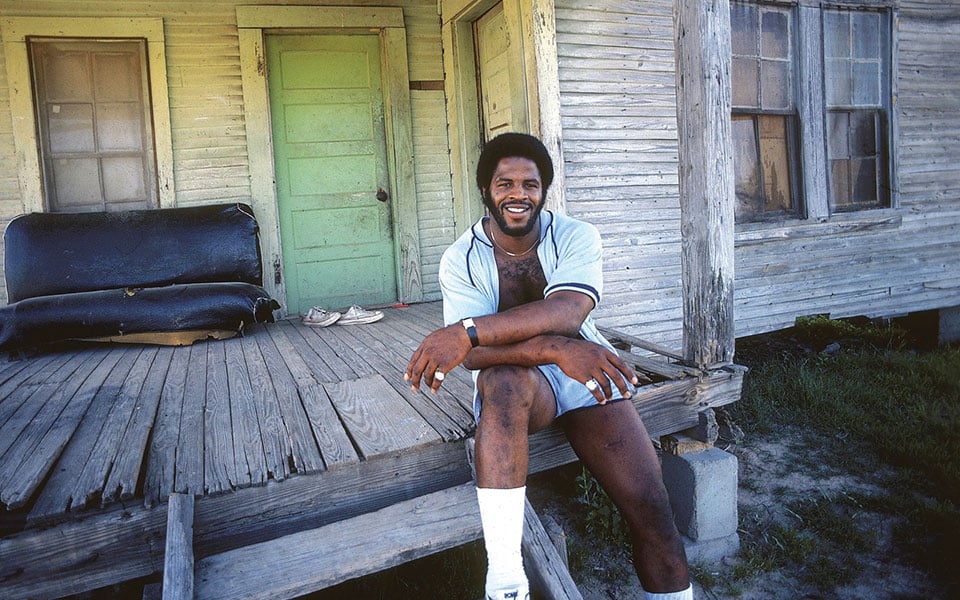

Above: As a popular black football player in historically segregated places, Campbell saw himself, in Price’s words, “as a catalyst for racial conciliation.”

In 1977, the University of Texas’ crushing running back, Earl Campbell, racked up 1,744 yards on the football field, 1,054 of those coming after initial contact with a defender on the other team. In other words, it was hard to stop Earl Campbell once he got going. He was famous and feared. When UT put out a press release advocating for Campbell to win the Heisman Trophy that year, it included a section titled “People Run Over.” Campbell won the award, the first Longhorn to do so.

But that he, a poor black kid from Tyler, Texas, was even playing for UT and its famed coach, Darrell Royal, for whom Texas’ concrete cathedral of a stadium is now named, is a hell of a story. UT had fielded an all-white team, the last to win a national championship without any black players, as late as 1969, just five years before Campbell enrolled.

By Asher Price

University of Texas Press

$27.95; 344 pages

Buy the book here.

All of this is captured in riveting detail and with crisp analysis in Asher Price’s new biography, Earl Campbell: Yards After Contact. In many ways, this book is a straightforward biography. We learn about Campbell’s time growing up in Tyler, as a sibling to 10 other children, and raised by Ann Campbell, a single mom who worked the rose fields to sustain her family. Price covers Campbell’s time in Austin, the player’s adjustment to living in the big city, and his domination on the field. And he follows Campbell to Houston, where he was drafted in 1978 to play for the Oilers, a down-and-out team that, for a few years, Campbell put on his back and carried to the playoffs.

But it’s more than a biography, too. Price uses Campbell’s story to explore the difficult history of race, segregation, integration, politics, and football across Texas.

Earl Campbell is of Texas, Price makes clear. He divides the book into three sections: one for Tyler, another for Austin, and the last for Houston. And then he shows how Campbell lived in each during times of major social and political transition.

Tyler was a profoundly proud Confederate place with a robust KKK chapter (the city even had a Klan newspaper at one point), and Campbell attended all-black schools until courts forced the desegregation of the high school right before he started there. He won that school a state football championship in 1973.

Meanwhile, in progressive Austin, the University of Texas responded to federal laws demanding desegregation by dragging its heels in all possible ways, including becoming “among the first public universities in the country to require entrance exams,” knowing that would limit the possibilities for black students. And the football team was “the very last bastion of whiteness at UT to integrate.”

After UT, Campbell played for the Oilers only a decade or so after the team ended its “Negro quota system” that made sure only five black players were on the team at one time. This happened against the backdrop of, Houston’s demographic shift away from its Republican roots toward the Democratic stronghold it is today.

To trace Campbell’s path and contextualize it within a larger history, Price crisscrossed the state, interviewing dozens of people, including Campbell, members of his family, and former teammates and coaches. Price visited archives, read memos and letters, consulted books, and pulled from newspaper and magazine coverage.

The University of Texas’ football team was “the very last bastion of whiteness at UT to integrate.”

As a popular black football player in historically segregated places, Campbell saw himself, in Price’s words, “as a catalyst for racial conciliation.” And it worked—up to a point. But Price convincingly argues that “though Earl Campbell tried, through carrying the football, to transcend race … race, exhaustingly, remained the prism through which Texans, and Americans, generally, saw one another.” Campbell was, after all, only a single man.

He’s paid a price, too, for the sport that gave him so much. Years of hard hits left Campbell with a whole host of injuries—knees in need of multiple surgeries, bone spurs on his spinal column, arthritis, and nerve damage—that eventually led to a painkiller addiction that sent him to rehab. Walking is now a challenge for the man who used to pull defenders along with him as he bolted down the field. This “Faustian bargain,” as Price calls it, that Campbell ultimately made, meant “trading long-term health for money, fame, and greatness.”

The need for this book was evident at the launch event for it at the Austin Central Library on September 5. Campbell is a prominent figure in UT history, both as a force on the field (Price describes him as “a black folk hero” on campus) and for the significant role he played in absolving Royal, who coached his last game at Texas during Campbell’s junior year, of charges of racism. The argument over whether Royal was racist for not integrating the team much sooner in his tenure remains a sore point for many fans. Indeed, most of the discussion at the launch event centered around the unanswerable question of Royal’s racism (a topic the book covers with nuance and care), with several community members defending Royal. Even now, at an event with Campbell’s name in the title and his face on the book, Royal’s legacy momentarily overshadowed Campbell’s.

The point of Earl Campbell: Yards After Contact, though, is to recenter the running back and his career in our understanding of the history of both football and race in Texas. We shouldn’t lose sight of that. It’s an important story, and Price tells it well.

Read more from the Observer:

-

American Health Care is Broken, Especially in Texas. What Can We Do About It? Physician Marty Makary’s new book shows how sky-high medical bills can ruin patients’ lives—but puts the burden on individuals to demand change.

-

Texas Leads in Polling Place Closures Since 2013: 750 polling places in Texas have been shuttered since Shelby v. Holder, the Supreme Court decision that released the state from federal oversight in changing its voter laws and practices.

-

Endangered River, Endangered Species: Trump’s border wall could decimate these rare species.