The Rise (and Fall?) of Michael Quinn Sullivan

The Republican kingmaker has had a bad couple of days in front of the state’s Ethics Commission—but will it stick?

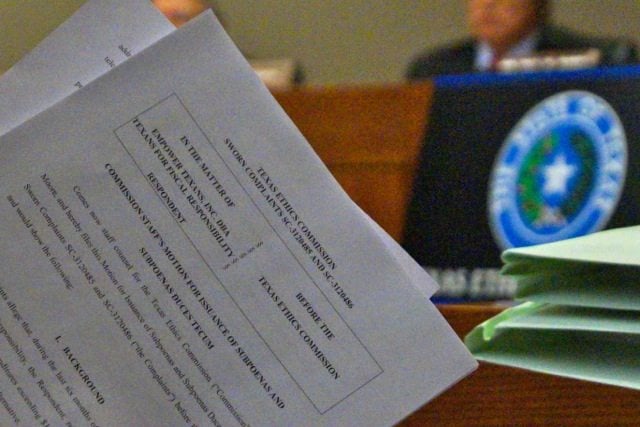

Above: Conservative activist Michael Quinn Sullivan

Michael Quinn Sullivan, the political warlord who’s striven to purify and shape the Texas Republican Party in line with his particular vision, has managed to outfox a number of threats to his would-be empire in the last couple years. But increased scrutiny from the Texas Ethics Commission over charges of impropriety and the question of so-called “dark money,” the fuel that powers Sullivan’s political activity, presents the possibility that the state political Establishment he’s always railed against, and by extension state government itself, has finally found a way to weaken him.

The Texas Ethics Commission is heading toward an extremely rare formal hearing on April 3 to consider four complaints lodged against MQS. The body met on Wednesday to figure out how to proceed with the commission’s probe. Republican state Rep. Jim Keffer and former Republican state Rep. Vicki Truitt, who had been aggressively targeted by Sullivan’s organizations, each filed two complaints, which were drafted by Austin lawyer Steve Bresnen. Truitt and Keffer both allege that MQS failed to register as a lobbyist while acting to influence the Legislature, and that Sullivan has violated existing campaign finance laws.

Then, on Thursday, the Ethics Commission approved, by a lopsided 6-2 margin, moving ahead with a rulemaking process that would require public disclosure of secret donors, including some of Sullivan’s fundraising and political activity. The anonymity of Sullivan’s operations has always been a key part of what gives him special power in state politics.

Among MQS’ political enemies—a long list which he seems intent to lengthen—are speaker of the House Joe Straus and his allies, and a wide assortment of Republicans he deems too moderate or timid. Rep. Keffer is considered an ally of Straus, and Truitt lost her seat in part because of Sullivan’s efforts.

On Wednesday, the Ethics Commission met to lay out the shape of future hearings, and select witnesses to subpoena on behalf of the opposing legal teams—a relatively pro forma event, and hardly a moment for courtroom theatrics.

But Sullivan’s lawyers, led by former Republican state Rep. Joe Nixon, went to war, seeming to declare the very existence of the Ethics Commission a threat to the American way of life. That approach isn’t altogether a surprise: When MQS (as he’s widely known—in private, his detractors call him “Mucus”) was presented with some of these complaints in November, he cast his interlocutors as Nazis. “Just like the Allies won the Battle of the Bulge,” said Sullivan, “so too will conservatives triumph over the speech-regulators at the Texas Ethics Commission.”

Specifically, he compared himself to Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, the American who in Bastogne in 1944 famously responded to a Nazi demand for surrender with a one-word answer: “Nuts.” (Sullivan literally wrote “Nuts” on his reply to the Ethics Commission.) But is MQS’ great crusade against the commission the Battle of the Bulge, or Pickett’s Charge?

Sullivan, who leads a set of closely-related groups under the banner of Empower Texans or Texans for Fiscal Responsibility has gained notoriety over the years for his unorthodox ruthless tactics. Making use of loopholes in campaign finance law, he uses his groups to accept anonymous donations and spend lavishly on select primary races, with the intent of unseating Republican legislators he feels are too moderate or are paying insufficient lip-service to him and his organizations.

Meanwhile, he conducts extensive outreach efforts to the state’s tea party groups. He’s adopted some of the same tactics Grover Norquist has used on the national level, asking Republicans to sign his “taxpayer pledge” and penalizing even his ideological allies if they don’t. He claims to speak for the conservative grassroots, but there’s evidence to the contrary. According to the Dallas Morning News, 99.8 percent of the money MQS’ Empower Texans PAC raised in the last two months of 2013 came from a single Midland oilman, Tim Dunn.

The result of his efforts: a less ideologically-diverse state Republican Party, one in seeming thrall to Sullivan. “Who’s in charge of the Republican party?” asked Texas Monthly’s Paul Burka in a recent post. “The answer could not be worse: it’s Michael Quinn Sullivan.”

But influence of this kind is premised on a consensus of fear, and in a democracy, that sort of influence isn’t the most sustainable kind, despite what Machiavelli said. “Power is perception,” says Craig McDonald of the left-leaning public interest group Texans for Public Justice. “He strikes a lot of fear in the hearts of the members of the Legislature. But that fear is not commensurate with the power he actually wields.” If observers expose the roots of MQS’ influence, McDonald says, “that perceived power will go away.”

That’s been an elusive goal for MQS’ Republican enemies in the last couple of years, but there are some signs the dynamic is changing. In 2013, the Texas Legislature considered a measure that would force public disclosure of “dark money,” dollars spent in campaigns by politically-active nonprofits that currently don’t have to disclose their donors. The measure effectively targeted MQS’ Texans for Fiscal Responsibility, but it was killed twice—once when it was stripped out of the Ethics Commission sunset bill, and once when a standalone bill was vetoed by Governor Perry.

But dumping money into primaries to challenge incumbent Republicans doesn’t win you many friends, and those who hope to constrain dark money’s influence in Texas politics are taking it up with the Ethics Commission. That led to last week’s double header: First, the Wednesday meeting considering ethics complaints against MQS and then the Thursday meeting considering a proposed disclosure rule for dark money.

Open disciplinary hearings of the Texas Ethics Commission—a notoriously hapless entity—almost never occur. McDonald, who’s been involved in campaign finance matters for decades, says it’s his first one. Complaints lodged with the body usually result in a settlement. Defendants don’t want their name in the papers, or the matter getting resolved in district court. But compromise is not the Michael Quinn Sullivan way.

Nixon, Sullivan’s lawyer, objected to the proposed length of future hearings, and he objected to the number of them. He objected to the fact that he couldn’t subpoena the Ethics Commission’s lawyers. He refused to submit a list of witnesses he’d like to subpoena, and did the same when asked about documents. He objected to the commission’s motion to subpoena Empower Texans employees, describing the attempt as a witch hunt that flew in the face of constitutional precedent, ethical propriety and the American way.

He objected to the idea of forcing lobbyists to register at all, arguing that the Ethics Commission helped maintain a lobbyist monopoly that disenfranchised average Texans. He objected (dozens of times) to the administrative code that the commission uses to conduct meetings, saying it contradicted obscure legislation from 1993 recommending the Ethics Commission standardize its hearing process. He talked ceaselessly about the violation of Sullivan’s right to due process. And Nixon sought to establish a right for his client to invoke the Fifth Amendment and choose not to testify without being subjected to a “negative inference” from the commission. That is to say, Sullivan appears intent not to testify, for all his talk about taking on the Ethics Commission.

At times, Nixon’s plaintive objections sounded like a studied approximation of earnest idealism. “Is this what we’ve devolved to?” he asked the room. “I know it’s frustrating to the commission, but we did not create this problem.”

But the commission’s chair, Jim Clancy, appeared unmoved.

“Oh, it’s not frustrating,” he said, before again attempting to get Nixon to cooperate with the process.

Steve Bresnen, the Austin lawyer who’s been active in mobilizing against Sullivan, says Nixon’s trying to set up a future legal challenge to the proceedings in district court that will get the complaints wiped—but thinks it will backfire.

“Nixon will do anything else but talk about the facts,” Bresnen told me. “He thinks some appellate court is going to come along and bail him out. But if the courts stand with the law as most recently enunciated by the Supreme Court, they’ll fail—and quite miserably at that.”

But the real threat to Sullivan’s empire came on Thursday, when the commission met to consider a rule—proposed by Bresnen—that would introduce a dark money disclosure requirement. Sullivan may want to fight the disciplinary motion, but it would probably amount to a slap on the wrist. It’s preserving his ability to redirect anonymous campaign donations that’s a pillar of his peculiar power over Texas politics.

So it should worry Sullivan that the commission—all eight of whom were appointed by Republican elected officials—seems inclined to tackle the dark money problem. The commissioners voted 6-2 to open Bresnen’s proposed rule to public comment—but even the two who voted against the rule, the chair and vice-chair, seemed to oppose Bresnen’s rule more than they did the idea of dark money disclosure, with Chairman Clancy telling the commission that “this issue is not going away.”

Action on either Bresnen’s rule or the disciplinary items are months away, with a lot of steps in between. But the commission could have killed the dark money rule on Thursday, and they didn’t, by a convincing margin. On Wednesday, just before his disciplinary hearing, Sullivan tweeted a characteristic example of the messianic zeal with which he approaches his enemies:

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive.” – C.S. Lewis

— Michael Q Sullivan (@MQSullivan) February 12, 2014

But a man who can only play offense, and never defense, can only find success for so long. And it’s clear more than ever that that the faction who hopes to force a high-water-mark on Michael Quinn Sullivan’s political influence in Texas is growing.