Money for Nothing: D.C. Dems View Texas as an ATM

A version of this story ran in the August 2016 issue.

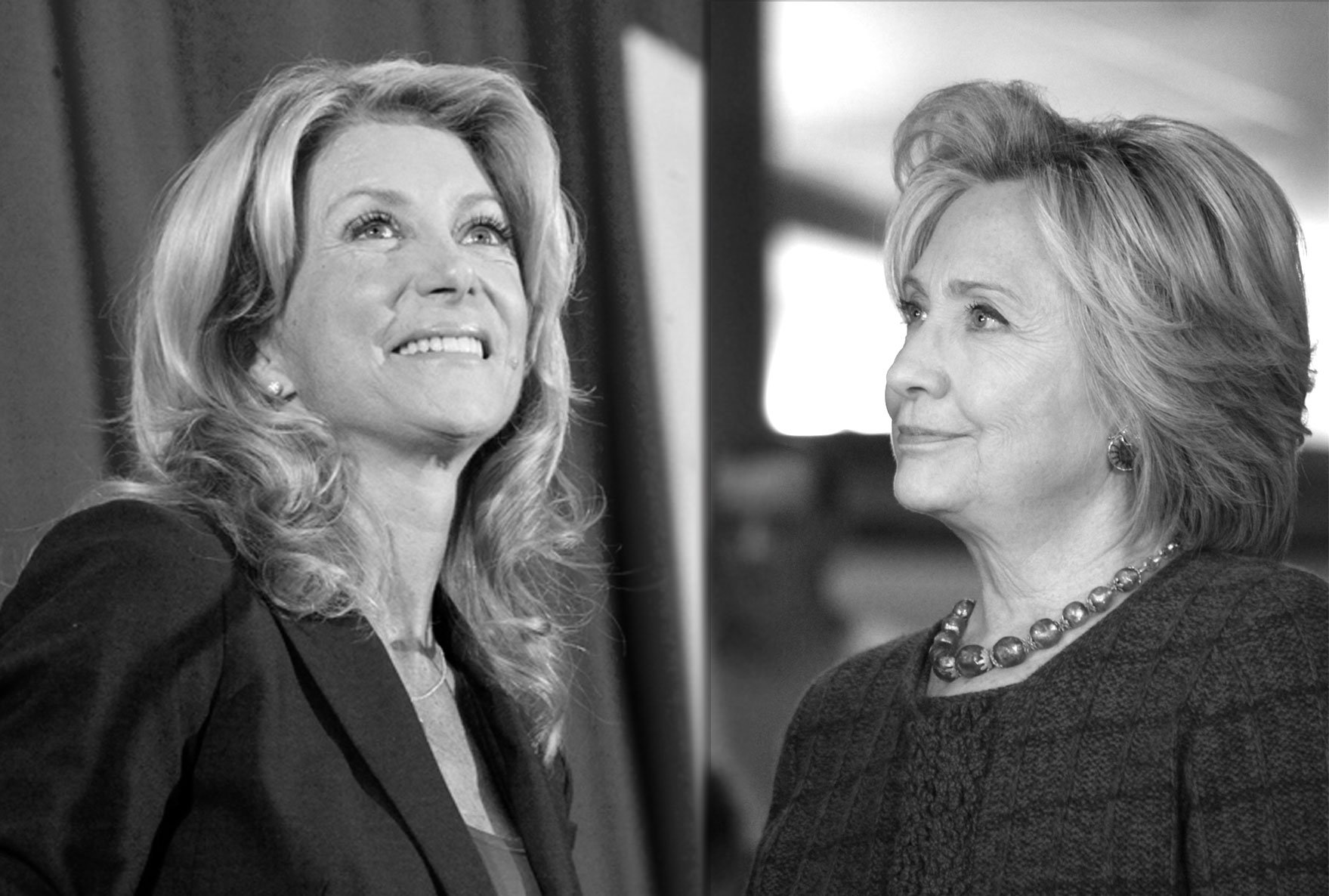

I don’t think of myself as a particularly sentimental guy, but Hillary Clinton’s declaration that her campaign leviathan would push to “flip Texas” in November put me in a nostalgic mood. Back when the 2014 Texas Democratic Convention was getting underway, I walked onto the patio bar at the Dallas Omni and saw a senior member of the Wendy Davis campaign I hadn’t met before. The fellow was from out of state, so I asked him: What brought you to Texas? I expected some partly-sincere answer about coming to fight for Wendy’s crusade. Instead, he told me it was money. The money was great.

Looked at one way, the honesty might have been refreshing, but he kept going: Someday, with all that scratch, he wanted to open up a cabaret in New York City. For now, he was stuck in Washington, D.C. “When I’m there I can’t stand it, but when I’m gone, I can’t wait to get back,” he said. His friends nodded. He spent the rest of the campaign arguing with pundits on Twitter and slowly alienating the media. He left Texas immediately after the election.

At the time, only true believers thought Davis could win, but the election still mattered. If the campaign closed strong, Democrats would have something to build on. If it flopped, it would set them back years. It was unnerving to meet someone so prominent in the campaign whose relationship to it not only seemed casual but who also was bad enough at the job that he’d admit as much while tipsy at a bar.

How many future leaders — promising candidates and campaigners alike — are getting lost or dropping out because of the dysfunction?

But it’s often hard to escape the feeling that many members of the professional Democratic political class see Texas like my friend at the Omni — as an ATM. Texas has a lot of rich donors, and that equals a lot of payroll here, as well as a generous bank for causes and campaigns around the country. Since 2000, Democratic politics here has organized itself largely around the dictates of various donors and their favored strategists, not around efficacy. It’s not that they’re comfortable with mediocrity — it’s just that no one’s ever really penalized for it.

The Clinton campaign probably couldn’t hurt turn-Texas-blue efforts, and her excitement about the prospect seems genuine. She spent a summer organizing in Texas in the early ’70s, a formative political moment for her. But it’s hard not to hear in Clinton’s call to “flip Texas” that same signal to big-dollar Texas donors: Give us your money, and we’ll work wonders in your state.

None of this is to say that Texans shouldn’t give to Clinton. We just shouldn’t invest too much hope in the transformative power of a presidential campaign advised by many of the same people who advised Texas campaigns in 2014.

It doesn’t seem like top-down change, and the flashy candidacies of charismatic leaders, has worked well for the party. But Democrats, now awaiting the glorious, prophesied return of the Castro brothers, seem stuck with the mindset. A significant majority of Texans live in the blue-ish metropolitan areas of the state’s five largest cities, plus the Rio Grande Valley, and that’s where you would expect to find the next generation of political talent, and young strategists to help them. But the left-leaning political apparatus in these places remains, for the most part, remarkably dysfunctional and disorganized. Local leadership positions are often treated as retirement gigs for those leaving the Legislature.

Take Houston, the capital of Democratic politics in the state. This year, extremely weak candidates won nominations for important local offices, such as Harris County Tax Assessor-Collector, which controls the voter rolls. The Houston delegation should be the powerhouse of the party in the Legislature. But it’s getting weaker, too. For a party that seems to have nowhere to go but up, this is a shaky foundation, upon which nothing solid can be built. How many future leaders — promising candidates and campaigners alike — are getting lost or dropping out because of the dysfunction? How much money will be spent before the party sorts itself out?