Colorado River Blues

NULL

“It’s interesting that you’re worried about what the lakes are going to look like down there and the pressure that you’re going to have to endure, and the front page of the paper showing what used to be lakes and are ultimately rivers now. I can certainly appreciate that.

“But, what about these small rural communities, where you drive down Main Street and the lights are all turned off, because there’s no economy left?” -Rice farmer Joe Crane, as quoted by News 8 Austin

“Let’s say you’re a marina owner, and you know rice farmers have two complete crops, and for them it’s business as usual. You might have some hard feelings, whether they’re reasonable or not. They haven’t suffered one single bit out of this.”-Cole Rowland, president of the Highland Lakes Group, as quoted in the Austin American-Statesman

These two recent quotes from individuals on opposite ends of the Colorado River Basin, each with a very different stake in the river, points to growing conflicts over water in Texas, between cities and rural areas, farmers and city-dwellers, people and wildlife, and among different regions of the state.

We keep hearing that a water crisis is imminent. Well, no, it’s here already.

A complex tug-of-war is well underway in the Colorado River Basin. The most visible division is between rice farmers along the coast, who require massive quantities of river water to flood their fields, and affluent homeowners around Lakes Travis and Buchanan who’ve watched the lake levels plummet.

Yesterday, the Lower Colorado River Authority was poised to make a decision on whether to declare the current drought an emergency topping the drought of record in the ’50s. If they had done so, it would have triggered an immediate halt to the release of water downstream to rice farms on the coast.

Instead, LCRA postponed the decision.

This drought, by some measures worse than the “drought of record” in the ’50s, is forcing water suppliers to make tough decisions now while giving us a taste of what lies ahead. Texas is booming but our supply of water is more or less fixed. In fact, if you believe a growing body of research that looks at regional impacts of climate change, we can expect the supply of surface water in this state to shrink considerably over the coming decades. “Drought” may become the new normal.

LCRA postponed their decision but the issue is not going away.

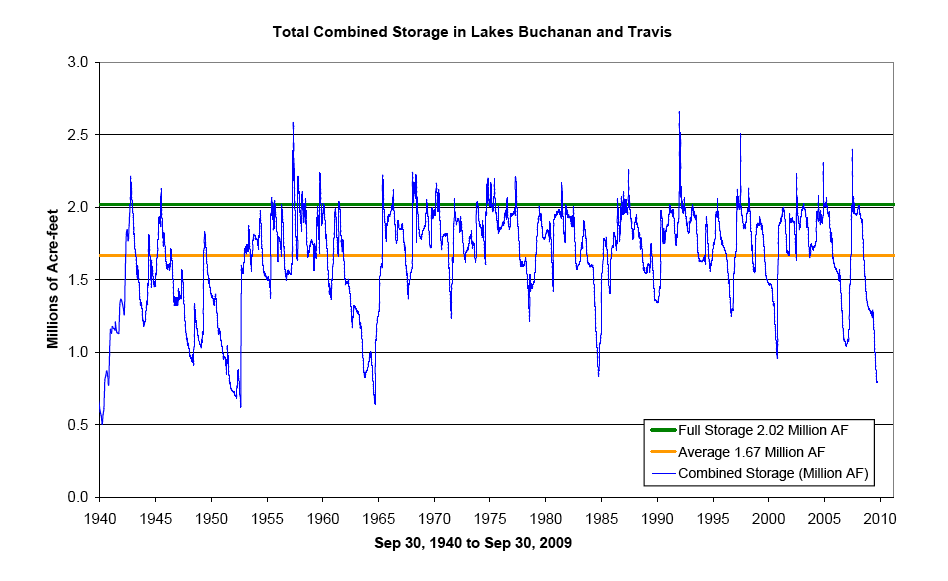

Despite the sustained rainfall in Central Texas, the LCRA-managed Highland Lakes, which provide drinking water for cities such as Austin, are still at a dismal 830,000 890,0000 acre-feet, about 40 42 percent capacity. The lakes have been lower before but not by much. [I wrote this post last night. Overnight rainfall has helped fill the lakes some, thus the revised figures.]

And the long-term view is that rapid population growth in Central Texas will trump the rice farmers. The Statesman:

In the long run, the cities and industries along the river basin are likely to win out. Projections in the state water plan forecast that between 2010 and 2060, partly because of water-saving technology, water use for irrigation will drop from 589,705 acre-feet per year to 468,743. During the same period, municipal use is estimated to increase from 226,437 acre-feet to 442,110 acre-feet.

***

There’s another upper vs. lower river basin controversy erupting in East Texas too. The issue is whether to allocate more water rights to a lower Neches River water authority for a proposed Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) plant on the coast. Interests on the upper Neches River are none too happy about the idea. From the Cherokeean Herald:

“Basically, the Lower Neches Valley Authority is trying to take our water,” said [Cherokee County Judge Chris] Davis. “They want our fresh drinking water to warm the liquefied natural gas, and then they are just going to dump it into the gulf. This is not a good use of our fresh water.”