Coal, An Obituary

Once, not long ago, it seemed that coal would conquer Texas. Just a few years ago, out-of-state developers and home-grown utilities, including TXU and NRG Energy, were clawing over each other to build new coal-fired power plants. Thanks to high natural gas prices and Texas’ deregulated power market, some of these companies were going to make a mint and turn Texas into the Coal Star State.

Now, many of the proposed plants have been unceremoniously scrapped. After an 800-megawatt coal plant comes online near Waco in April, it’s possible that there will be no new coal-fired power plants built in the state ever again. Just today, the developers of White Stallion, a huge 1,2000-megawatt coal plant near Bay City, announced that they were pulling the plug on the project.

It’s a turn of events that would’ve seemed unthinkable in the heady mid-decade coal rush.

What happened?

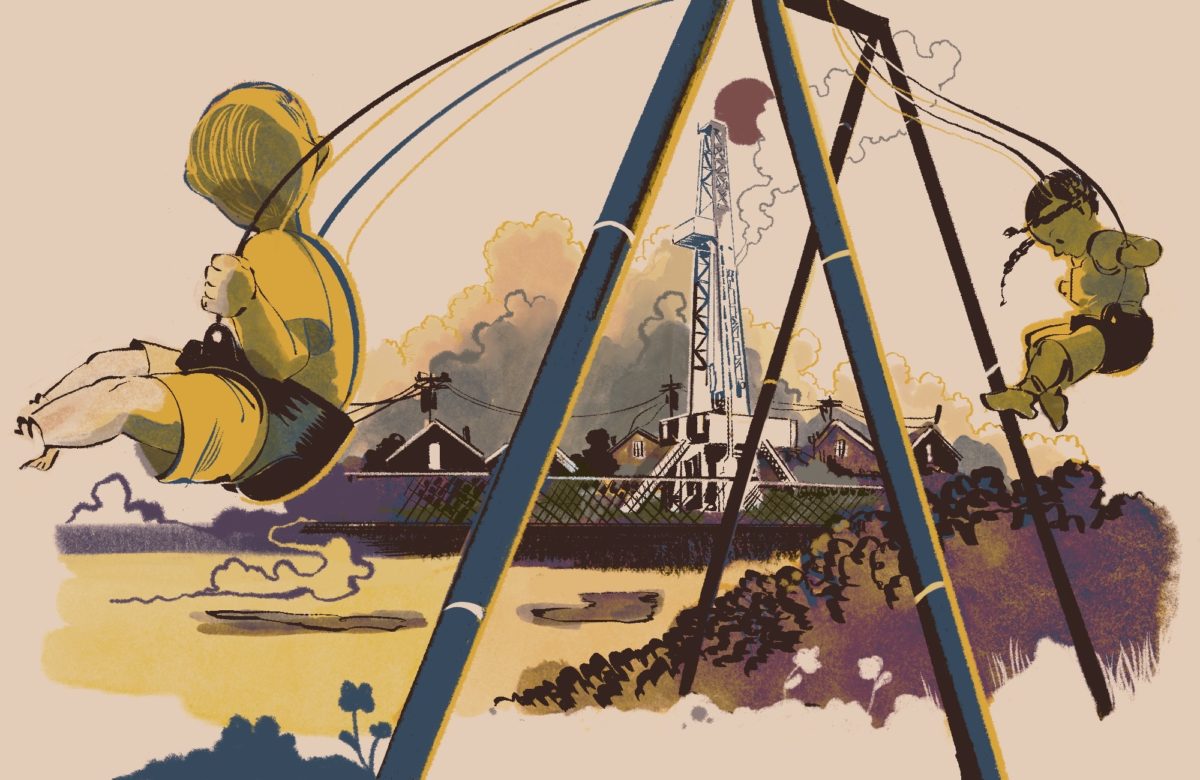

Those with a stake in the debate will emphasize different causes, but the reality is that coal’s undoing is owed to a happy collision of factors. First, using coal as a fuel for power no longer makes economic sense, due in large part to the natural gas frenzy. Second, the Obama EPA has ratcheted up regulations targeting coal’s outsized emissions of mercury, sulfur dioxide, ozone-forming gasses and carbon. Third, environmentalists and local communities put up one hell of a fight. The Sierra Club and other environmental groups made Texas ground zero for stopping coal in its tracks. Their working theory: if coal could be whipped in Texas, it could be whipped anywhere. The big environmental groups were joined by ranchers, farmers, students, doctors, hippies, hipsters and hillbillies in a plant-by-plant battle. That war of attrition seems to have paid off.

Consider one of the latest casualty: The Las Brisas Energy Center, a $3 billion, 1,320-megawatt power plant slated for the Corpus Christi Ship Channel. (Las Brisas would burn petroleum coke, or pet-coke, a refinery byproduct very similar to coal.)

Announced in 2008, the Las Brisas (“the breezes”) project folded in January after investor interest fizzled. Chase Power CEO Dave Freysinger blamed Las Brisas’ demise on “regulatory obstacles purposefully erected” by the EPA. But that’s only part of the story. From the get-go, Las Brisas faced stiff opposition from folks in Corpus Christi, including the powerful medical establishment. (My grandfather was a dermatologist in Corpus, but unfortunately I never got the chance to ask him why the docs there have such great influence.)

The doctors marshaled their expertise to blast Las Brisas as a “health care disaster” for Corpus Christi, arguing that the plant’s pollution would increase the city’s already-high rates of asthma, birth defects and other health problems.

Despite state regulators going out of their way to help Las Brisas get its permits, Chase Power had a tough time proving it could comply with the Clean Air Act. Twice, administrative law judges recommended that the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality reject the company’s air permit, but Rick Perry’s appointees kept it alive anyway. In July, a Travis County district judge reversed TCEQ’s decision, tossing out the air permit. Then the EPA warned the company that the proposed plant would have trouble meeting new limits on greenhouse gas pollution.

Meanwhile, coal stopped making economic sense. In short, coal got fracked. The drilling frenzy, including in Corpus’ backyard of the Eagle Ford Shale, has forced natural gas prices down. That in turn drove down the marginal cost of electricity in Texas and made coal much less attractive. As the Corpus Christi Caller-Times editorialized, “the economic justification for squeezing electricity from inherently dirty, underwhelmingly energetic petroleum coke became unconvincing.”

The story for White Stallion is similar too: local opposition that started small but grew (it certainly helped that the conservative county judge turned against it); major regulatory impasses for the company; and a bottom-line that had the bottom fall out of it.

The White Stallion developers also didn’t do themselves any favors with ridiculous claims that the plant would lower electricity rates locally and that their traditional coal plant was a “clean coal” facility. The company’s website claimed the plant would use the “most environmentally advanced, cleanest, commercially proven, emission-lowering technology available.” In fact, it was middling when it came to new coal plants in Texas, which is to say it would’ve emitted large amounts of ozone-forming gasses, particulate matter, mercury as well as massive quantities of carbon.

In 2009, I spent several days in Matagorda County in 2009 working on a feature about how Texas was moving in the opposite direction of the rest of the nation when it came to coal. At that time, it seemed like Texas was going to double-down. Despite a dedicated group of local activists opposed to White Stallion, at that time it seemed the economic arguments would prevail in Bay City, where the unemployment rate has been stubbornly high. How ironic then that today, of all days, Gov. Rick Perry announced that a company would be opening a $1.5 billion pipe mill plant to service the natural gas boom in the Eagle Ford Shale and other shale plays. Natural gas killed coal and now it gets the last laugh.

It’s weird to say, but get used to it: Coal is expensive.

Wind power is cheaper. Even solar is fixing to eat coal’s lunch, if it isn’t already doing so. El Paso Electric Company recently agreed to buy power from a New Mexico solar farm for a little under 6 cents per kilowatt-hour. A new coal plant costs twice as much.

So is King Coal dead in Texas? No, but he’s been knocked off his throne. Texas still gets about a third of its power from coal-fired power plants. We’re still the top importer of coal in the U.S. Texas still leads the nation in climate-change-causing carbon emissions. And the evils of coal live on even after the smokestacks are taken down. That carbon is stuck in the atmosphere; that mercury sits undisturbed in the sediment of lakes and the flesh of fish.

The next task for opponents of coal may seem impossible: Shutting down existing plants in Texas. It’s actually not that far-fetched. San Antonio’s CPS Energy announced last year that it would retire one of its coal plants early. And the city of Austin is exploring ways to pull out of the nearby Fayette Power Project.

Coal hasn’t been buried yet. But its obituary is already being written.