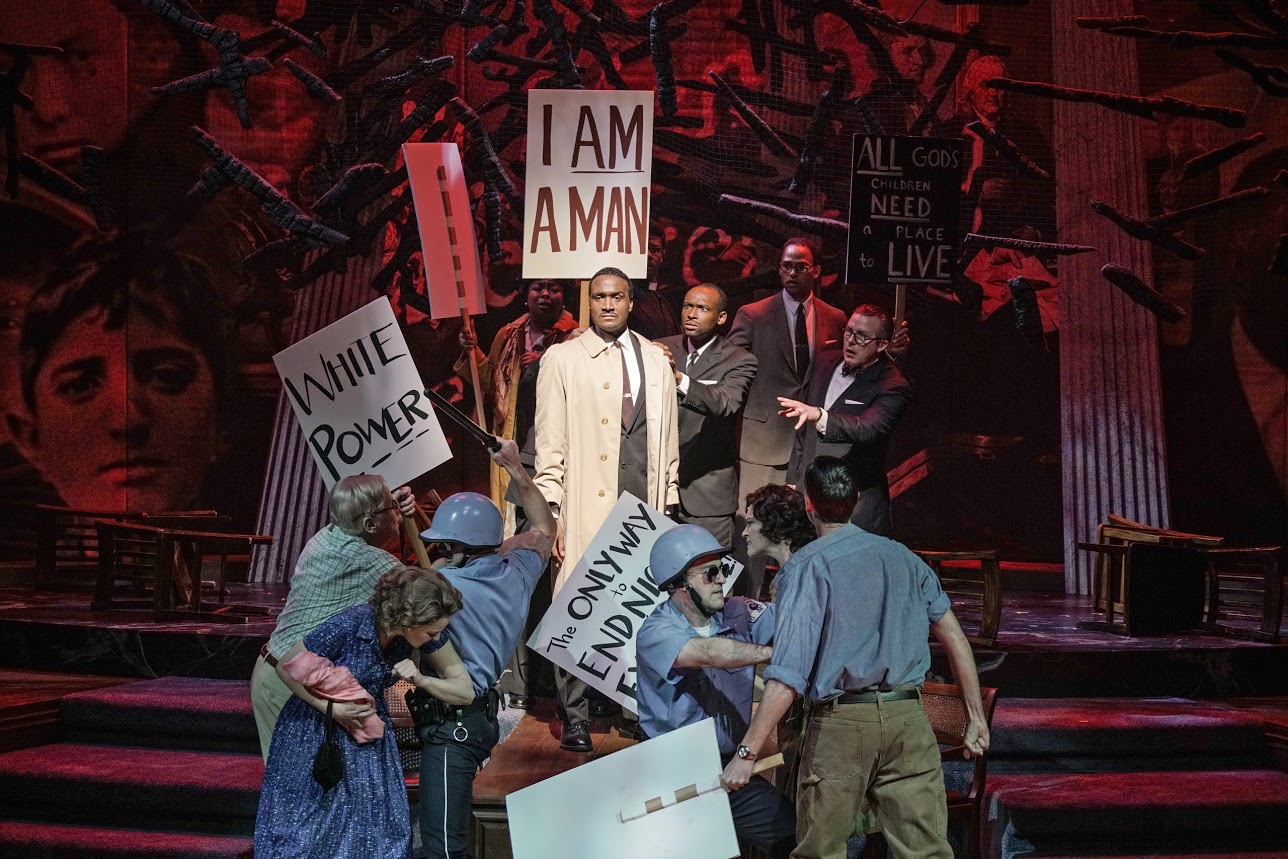

From the Archives: LBJ, Civil Rights and the Long March Forward

Four pieces published in the Observer in 1964 that reflect that pivotal year

Above: President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

This week, the LBJ Presidential Library at the University of Texas is hosting a three-day Civil Rights Summit to mark the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act. President Barack Obama and three former presidents—Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush—are scheduled to speak.

From its founding in 1954, The Texas Observer has strived to cover the ongoing civil rights struggle, even when—especially when—the mainstream press in Texas was ignoring, or impugning, the efforts of activists to achieve full equality.

We’ve selected four pieces published in the Observer in 1964 that reflect that pivotal year. In “Integration in Texas,” founding editor Ronnie Dugger writes of the “thaw” in race relations taking place across Texas. In “To Be From Mississippi,” Peggy Neely Milner writes about why she left Mississippi and can never return. In “President Johnson and His Program,” the legendary Maury Maverick Jr. urges Texans to “rally to the good fight for the man from the Pedernales River.” Finally, in “After the Riot,” James Presley takes stock of integration in Texarkana, where, in 1964, “violence still throbs just beneath the surface.”

Integration in Texas

By Ronnie Dugger

March 6, 1964

The valley of segregation, below the white icy mountain, has been dry for lo these many years. The thaw, gradual like the coming of a millennial summer, has trickled into the valley a slowly rising river, lifting leaf by leaf, twig by twig, worrying loose great dead trees from their rotting roots, as it rises ever slowly, but steadily does rise. Surveying Texas since the Observer’s last report on the thaw, (“Texas Is Integrating,” Obs. June 28, 1963,) we must notice that the rising river has borne off some thickets of piled-up brush, some whole fallen-over timbers, but the valley is still wide and much of it cluttered and dry; the winter that began Nov. 22 has not yet become the spring.

The assassination, for instance, cut off rising expressions of discontent among the 3,200 students at Prairie View A&M College near Hempstead (“the exception” noted in the Observer’s account of Houston as a backwater of the civil rights revolt, Obs. Nov. 15, ’63). The discontent found focus in an economic boycott of the merchants in Hempstead, and it found an on-campus target when the administration of the school refused to support the boycott. For the homecoming football game with Bishop College Nov. 9. the students stayed away to chastise the administration, and the stands were almost vacant—estimates did not go higher than 100 fans in attendance. On Nov. 16, three white ministers joined students in picketing G. Kelley’s Steak House and the KC Steak House on Highway 290, which passes through Hempstead. Then came Nov. 22…

To Be From Mississippi

By Peggy Neely Milner

July 10, 1964

I was born in Mississippi and lived there until I was 23 years old. Most of my life I never thought about equality or unequality—about segregation or integration. Things were as they were and there was no reason to ever think or talk about them. There were few threats to “our way of life,” and besides the men in my family and my community could always handle any situation with either a strap or a shotgun.

I was never taught to hate the Negro—nor was I ever taught to treat the Negro as a fellow human being. The Negroes I knew were treated as if they were mentally disturbed members of my family—people who were not quite right in the head. We were proud of those who learned to read and write and were ashamed of those who fought and got cut up and who made whiskey and got drunk and got put in jail on Saturday night. But they were “ours” and they were “good niggers,” so we got them out of jail the next morning. Besides, we had lots of good laughs over what “Old So and So” said to the sheriff when he got jailed. They were fed what was left over from our table, they were clothed in our old clothes, their houses were on our land, and their furniture was what we gave them when we got new; they were taken care of. Our cook had five children of her own—each by a different man so my mother said—and yet she was at our house every day from daylight till after dark. She got off every other Sunday to go to her own church, but she had fixed our dinner before she left and came back right after church to put it on the table and to clean up the kitchen. She cooked and cleaned our house, sewed and washed and ironed and mended our clothes, raised our garden and did all the canning and preserving, and in her spare time looked after my brother and me. I loved her very much but she was never anything to me but our cook…

After the Riot

By James Presley

August 21, 1964

In 1917 Texarkana businessmen formed an interracial council. It was not a happy venture, and did not last long. The one meeting ended in a near-riot, and for 47 years Negro-white relations continued catch-as-catch-can, sometimes simmering, sometimes exploding. But last month, after the new civil rights bill became law and there was another near riot, this twin city’s power structure tried again. The new beginning promises to be amicable and possibly profitable.

Four persons were shot on a Sunday afternoon, July 5, at Lake Texarkana; the next day Negroes and whites met in an emergency session. In the background were the televised proceeding of St. Augustine, Fla. “We are not going to be another St. Augustine,” one businessman said.

Texarkana had not prepared for difficuties that were certain to proceed from the enactment of the new civil rights law. This is probably typical of this entire section of East Texas. The junior college and Catholic and Episcopalian schools here were integrated, and both public school systems—Arkansas and Texas—begin desegregation this fall, but there was no master plan to desegregate public acommodations…

President Johnson and His Program

By Maury Maverick, Jr.

September 4, 1964

In the early Greek democracies, every man had his public duties to perform . . . . sometimes as a soldier, sometimes as an office-holder, sometimes as one participatingin an organization. To those of that era who would not concern themselves with politics the name “idiot” was applied, and so, interestingly enough, the original meaning of the word idiot, both in Greek and later in early English, meant a person not holding public office or not participating in public affairs. When we participate in a political organization—when we involve ourselves with the politics of our home town, history says that this is an honorable endeavor.

People have to understand that they are not always right, be they rich or poor, black or white, you or me, Good Government League or the Democratic Coalition, organized labor or the business community. Everywhere in America, and at every level, a loyal opposition is needed.

This is what Walter Lippman meant when he wrote. “The opposition is indispensable. A good statesman, like any other sensible human being, always learns more from his opponents than from his fervent supporters. . . . In a democracy the opposition not only is tolerated as constitutional, but must be maintained because it is in fact indispensable.”…