Why Did the City of Dallas Censor (and then Reinstate) a Public Art Project It Helped Fund?

This isn’t the first time Dallasites have gotten cold feet after agreeing to host public art that grapples with issues of race and class.

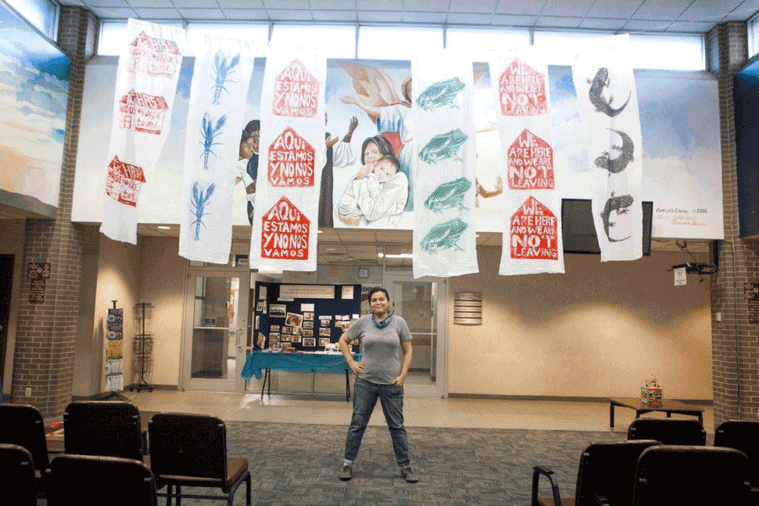

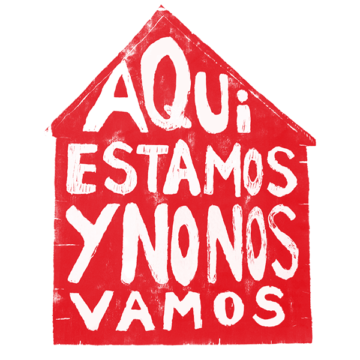

Artist Angela Faz installed six cloth banners with woodcut prints at a community center in a working-class West Dallas neighborhood on April 4. The colorful banners — three of which were printed with images of local fauna, such as crawfish and salamanders, and three with slogans like “Aquí estámos y no nos vamos” (“We are here and we are not leaving”) — hung from the ceiling over a room where people wait for health screenings, legal aid and senior services. Faz’s piece was one part of a multi-venue art project called Decolonize Dallas that asked local artists of color to create works based on neighborhoods they had ties to.

The next day, however, one of the project’s curators, Carol Zou, received an email from Silvia Ulloa, an employee at the West Dallas Multipurpose Center, with the subject line “Banners????” “Please call me, urgent!” the message read. Zou says Ulloa told her that a supervisor at the center had a problem with the phrases on the banners. The city’s Office of Cultural Affairs had contributed $7,500 toward Decolonize Dallas, about half of the project’s total funding.

Some of the banners included quotes from residents, such as “This house has a lot of value to me,” which evoked issues of gentrification and an ongoing affordable housing crisis in the neighborhood. And, apparently, they made someone uncomfortable.

“I was extraordinarily surprised,” Zou said. “I think you can say much more inflammatory things about what’s happening in West Dallas.” A few toads and crawfish paired with “Aquí estámos” hardly seemed controversial.

The city took down all six banners on April 6. On April 10, Faz was allowed to rehang the three animal banners.

Faz grew up in the West Dallas neighborhood of Ledbetter. She said that her aunt, Mary Garza, is among those looking for a place to live after receiving eviction notices from landlord HMK, Ltd. More than 300 families are in limbo due to the mass eviction, which is scheduled for June 3 amid an ongoing struggle between residents, who want to stay in their low-rent homes; the landlord, who says there’s no money to bring the apartments to code; and city leadership, which has been vague with stated plans to help.

Faz said that some of the quotes on the prints came from interviews with West Dallas residents and that she chose to depict a salamander, the Texas prairie crawfish and the Gulf Coast toad because they are all species she sees less often since the neighborhood began gentrifying.

“These animals were here, they’re not there, maybe [community members] have some memories of the nighttime sounds,” she said. “I was trying to use the banners to conjure some positive memories but also be very thought-provoking.”

“If Dallas wants to be an ambassador of culture and include all the different points of view, then I feel like there should be some transparency.”

The city changed its tune after Zou and Ratcliff published a column in D Magazine airing their concerns on April 17. On Wednesday, the Office of Cultural Affairs issued a statement saying all Faz’s panels were now welcome at the West Dallas Multipurpose Center. Reached by phone, Jennifer Scripps, the office’s director, declined to say who had the problem with the banners and what about them was objectionable.

“I’m not sure who that is — all I can tell you is what I’ve been able to make happen,” Scripps said. “People don’t like surprises there. It’s not a typical art site, let’s put it that way. Decolonize Dallas is so much more than this. It’s been a really wonderful thing that we did.”

This isn’t the first time Dallasites have gotten cold feet after agreeing to host public art that grapples with issues of race and class. As Zou and Ratcliff’s column acknowledged, a project to add historical markers acknowledging the racist past of the city’s African-American parks is on hold after the artists accused their funders of censorship last year.

For her part, Faz said she’ll reinstall the banners if the city issues a more specific public apology.

“If Dallas wants to be an ambassador of culture and include all the different points of view, then I feel like there should be some transparency,” Faz said.

In any case, Faz plans to make more of the prints and use the proceeds to help her aunt secure a place to live. The banners are the first known artwork based on the West Dallas eviction crisis, Zou said.