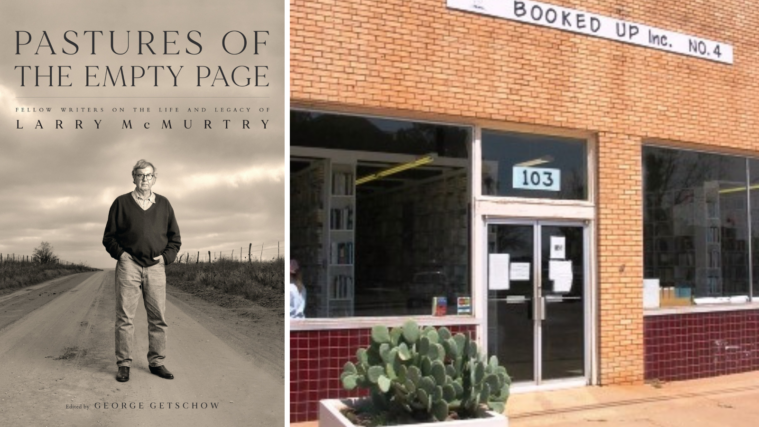

Boom and Bust in Big Spring

"The Kings of Big Spring" conveys the difficulties and deprivations stared down by the Depression era's 99 percent.

A version of this story ran in the February 2018 issue.

Above: A pipe runs from a water well to a storage pit in Big Spring, Texas.

Profundity alert: when a book’s subtitle contains the word “American,” never mind the phrase “American Dream,” you know you’re dealing with an author — or at least a marketing department — with ambitions beyond the story at hand. (I’ve done it too, which I mention only to establish my sheepish bona fides for the critique.)

And if this book’s “American Dream” subtitle doesn’t sufficiently convey the reach of its aspiration, the promo copy swoops in to assert: “In telling the story of four generations of his family, Bryan Mealer also tells the story of how America came to be.”

Not to put too fine a point on it, but, well, no, he doesn’t. He expends some strategically positioned paragraphs to convey a broad-stroke awareness of what was going on in America at large, economically and culturally, but telling the American story in microcosm hardly seems to be what Mealer is up to here. And despite what a publicity department may think, he needn’t try. He’s already got any author’s best weapon at his disposal: a fascinating family. The Kings of Big Spring is the story of four generations of that family making their ways in the world. And it’s a much more satisfying story on those plain terms, without any half-hung bunting of national resonance.

by Bryan Mealer

Flatiron Books

384 pages; $27.99

The story starts in 1892, when Mealer’s great-grandfather leaves the hardscrabble moonshine economy of Georgia to follow a brother and the promise of opportunity to East Texas. Thus begins a multigenerational saga of a family chasing booms and running from busts — frequently in the form of drought or boll weevils — until it finally settles, more or less, in Big Spring, that semi-obscure oil patch nephew to Midland and Odessa, and itself perpetually subject to the desperate ebb and exhilarating flow of the oil economy of the Permian Basin.

I’m not going to try to give a coherent account of those four generations. The advance copy I read has two pages of “[insert]” placeholders where the family tree will go in the finished book, and more than once I wished I could access them. Suffice to say that the tree culminates, within this story’s confines, in Bryan Mealer, a former reporter and Austin author of three previous books. And with the exception of a brief prologue and epilogue, Mealer is a remarkably understated presence. There’s nothing even remotely memoirish in The Kings of Big Spring, just a few brief personal memories added for color. If The Kings of Big Spring isn’t really about America, neither is it about its author.

Perhaps as a result, the book’s first half is a pretty slow go. Mealer recounts a century of his family’s history — marriages and deaths and births and dramatic cruxes — and he establishes context and deploys anecdote with economical skill, but still, it’s mostly a matter of various family members coming and going, either searching for something better or running from something worse.

The narrative starts to gain momentum with the arrival of the author’s father, Bobby, who’s 26 when he leaves the sink-or-soar cycles of Big Spring for a stable job near Houston, only to be pulled back almost immediately by a stroke of fortune: Big Spring is gushing oil again, and Bobby’s childhood friend Grady needs a partner.

Bobby, married with three kids, takes the leap, entering Big Spring’s oil-boom fray as Grady’s wingman. And it’s Grady — perhaps curiously for a family saga — who turns out to be the book’s most interesting character: an apparent gold digger (he’s conveniently married into one of Big Spring’s former first families), a bit of a grifter, cocaine aficionado, alcoholic and a flamboyant flaunter of wealth whose hobbies include flying family and friends on private jets to Amarillo for steak dinners, or to the Bahamas to party, with as much notice as another man might give to running to the corner store for a six-pack.

The book’s most vivid portrait, though, isn’t of Grady, or Big Spring, or even Mealer’s large and mostly colorful cast of kin, but of the capriciousness — occasionally lucky, frequently otherwise — of circumstance on a family’s fortunes, and the ways in which bald necessity drives destiny. Mealer’s forebears worked hard not to thrive, but to survive. If the wood ran out in wintertime, they burned scrap tires in the stove. If roughneck work dried up, they bought trucks and hauled dirt. The Kings of Big Spring conveys a satisfying and sobering sense of the difficulties and deprivations stared down by the Depression era’s 99 percent.

Mealer is so restrained in his descriptions of triumph and glamour, and so emotionally disengaged from [his story’s] traumas, that the book is more anodyne than expansive.

But if there’s plenty of movement and action, there’s nothing you’d quite call a plot. The book follows the family members’ rises and falls, mimicking the busts and booms that drive them. These trajectories are episodic, just like in real life, striking on the apparent whims of weather, geology and happenstance. And a good number of those individual arcs are punctuated with literal come-to-Jesus moments, mostly involving men at the ends of various ropes trying to set themselves straight. There’s nothing at all treacly about Mealer’s descriptions of the conversions — in fact, Mealer is so resolutely straightforward it’s hard to sense any authorial attitude at all, which is a neat and admirable trick.

Mealer steadfastly declines to offer almost any comment at all on his story, which includes more than a fair amount of spousal abuse and alcoholism, never mind class struggle. There’s not so much as a feint toward current discourse on those issues. This is not a book of analysis, or of judgment.

And in that sense, it seems almost old-fashioned, from the mileposting chapter summaries (“A journey back east … then west along the rails … the Dust Bowl begins on the plains … cotton rebounds …”) to the book’s dominant tone, which, however muted, is one of wonder at life’s unpredictable pageant, and humility in the face of hardship and success alike. Maybe that’s why, having read the final page of the advance copy, it’s hard to avoid noticing the publisher’s publicity plan, with its “Christian Market Outreach.”

If the book’s subtitle carries a whiff of overreach, that marketing plan rankles of limitation. The Kings of Big Spring may not be the story of how America came to be, but it is a compelling story of how one family worked toward, if not the American Dream (whatever that is), then at least a comfortable modicum of security and stability. And that story should prove satisfying to readers of any religion, or none at all.

Texas, as suits its sometimes justified arrogance, has a knack for producing epic saga-as-national-mythos literature. Edna Ferber did it with Giant. Philipp Meyer did it with The Son. But this book isn’t those books. Most obviously, it’s not fiction. This is an ostensibly true story, undertaken without any apparent creative license, and Mealer is so restrained in his descriptions of triumph and glamour, and so emotionally disengaged from its traumas, that the book is more anodyne than expansive.

You could read that as a criticism, if you were looking for more, but you could also take it as evidence of Mealer’s care and affection for his story, and how much he trusts it. He’s right to. It’s a good story.