Bill Would Include Pregnant Texans in End-of-Life Law

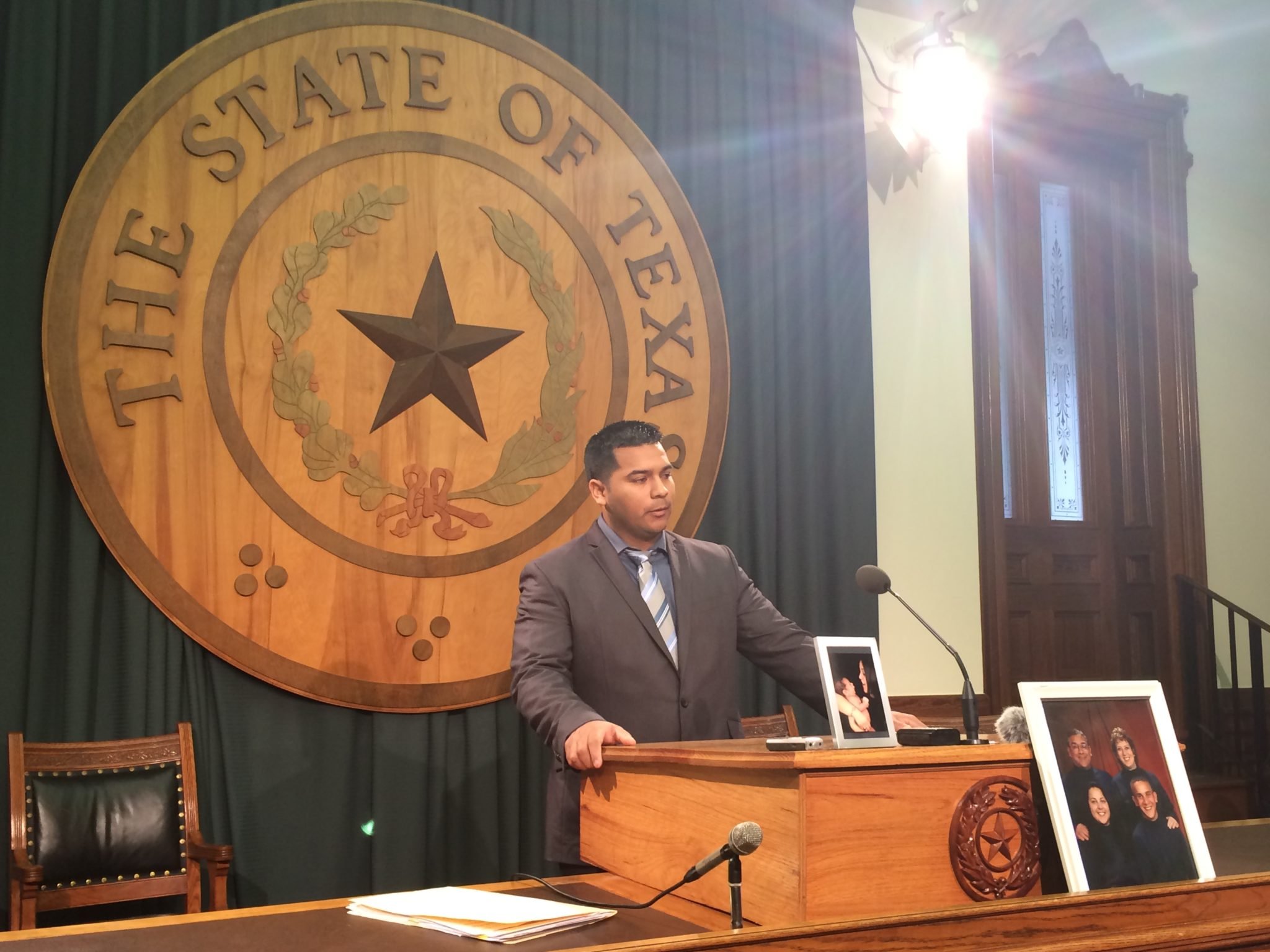

Above: Erick Muñoz, husband of Marlise Muñoz, addresses reporters at the Texas Capitol.

For nearly two months, Lynne and Ernest Machado’s pregnant, brain-dead daughter was kept alive against the family’s wishes. After collapsing in her home and suffering a pulmonary embolism in November 2013, Marlise Muñoz was declared brain-dead by a hospital in Fort Worth and put on life support. She was 14 weeks pregnant with her second child.

Despite her family saying that Muñoz had communicated that she wanted to be immediately taken off life support should something catastrophic occur, the hospital refused, citing a provision of Texas’ advance directive law that states doctors “may not withdraw or withhold life-sustaining treatment … from a pregnant patient.” Muñoz’s husband, Erick, and her parents sued the hospital, ultimately winning their case and the right to bury Marlise.

Today, Lynne said her family was put through a “torturous hell” while fighting the hospital.

“It was horrible, it was traumatic, what they did to her body,” she told the Observer. “We knew she had died, we knew she was gone. What we didn’t plan on was that a pregnant woman in Texas forfeits her rights the minute she becomes pregnant.”

Now, more than a year later, Marlise’s family is working to make sure that no Texas family has to go through what they did. Today, they stood alongside state Rep. Elliott Naishtat (D-Austin) as he announced a bill called “Marlise’s Law,” which would remove the so-called pregnancy exclusion in Texas’ advance directive law.

“Doctors and hospitals should not be compelled by the law to impose medical interventions over the objections of a dying patient and her family,” Naishtat said at a press conference Thursday at the Capitol. “These changes will permit the pregnant patient to control her care, her treatment, by giving instructions to health care providers to administer, withhold, or withdraw life-sustaining treatment.”

Currently, more than 30 states have similar pregnancy exclusion provisions in their end-of-life laws. In Texas, the advance directive document includes this provision: “I understand that under Texas law this directive has no effect if I have been diagnosed as pregnant.”

Rebecca Robertson, a lawyer with the ACLU of Texas, pointed out that the law blatantly discriminates against pregnant patients.

“It makes pregnant women second-class citizens because they no longer have the right to decide for themselves,” she said.

Marlise and her family had decided long ago that should a catastrophe occur, none of them would want to be kept alive by machines. Still, they were forced to endure a weeks-long court battle because Marlise was pregnant. Erick told reporters that his wife was family-oriented, a good mother and confident in her decision to forego end-of-life medical treatment.

“It’s a family matter,” he said Thursday at the Capitol. “It should be handled as such.”

While Naishtat’s bill would remove the pregnancy exclusion provision, a bill by state Rep. Matt Krause (R-Fort Worth) would tighten it. Filed at the end of February, Krause’s House Bill 1901 would require a hospital to keep a pregnant woman on life-support “regardless of whether there is irreversible cessation of all spontaneous brain function of the pregnant patient … and if the life-sustaining treatment is enabling the unborn child to mature.” Dubbed the “Unborn Child Due Process Act,” Krause’s bill would also require the Texas attorney general to appoint a lawyer for the unborn fetus from a “registry” that the attorney general’s office would create.

“It’s my position that if a baby is still continuing to grow and develop, then that means the mother cannot be brain dead, there has to be something that’s allowing that baby to grow and develop,” he told the Observer. The lawyer “would just give a voice to that unborn child during court proceedings.”

Robertson called Krause’s idea “unprecedented.”

“The government’s going to get involved on behalf of the fetus, as if the grandparents, husband, were somehow not looking out for the interest of the fetus,” she said. “You can see where that might be applied in much broader circumstances, this idea that when you become pregnant you lose your autonomy.”

Krause’s bill was been referred to the House State Affairs committee.