Dozens Caught in Land Rights Fight Over Trans-Pecos Pipeline

A version of this story ran in the May 2016 issue.

James Spriggs, a 70-year-old west Texas rancher, is dealing with what he calls a lose-lose situation. Spriggs owns a 4,400-acre ranch south of Marfa and is one of about 45 landowners in the Big Bend region recently slapped with a condemnation lawsuit by Energy Transfer Partners, a Dallas company looking to build a 143-mile pipeline from Texas into Mexico.

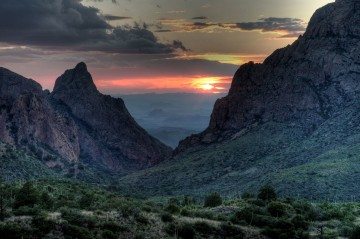

Once constructed, the Trans-Pecos pipeline would move natural gas from the Permian Basin to Mexico, crossing some of the last remaining pristine parts of the state. In the last year, Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) has faced fierce opposition from a coalition of conservationists and ranchers. They worry that the pipeline will pose a threat to public safety and that it will destroy the natural beauty that Big Bend is known for.

But opponents have had few opportunities to block the company procedurally. Despite Texans’ love of private property rights, the state’s eminent domain laws heavily favor the condemnor. Requests for common carrier status, which gives companies the power of eminent domain, are rubber-stamped by regulators with few questions. On May 5, ETP received the greenlight from the federal energy commission, clearing the last regulatory hurdle.

“You spend your life saving for a piece of property and they treat you like a second-class citizen.”

“The land is worth 10 times what they’re offering,” Spriggs told the Observer. “You spend your life saving for a piece of property and they treat you like a second-class citizen. It isn’t right at all.”

What Spriggs and his neighbors are facing is not uncommon. Landowners have fought similar battles against the Keystone XL expansion in East Texas and less controversial projects in the Barnett and Eagle Ford shale regions. But repeated efforts to overhaul eminent domain laws have failed.

After last year’s legislative session, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick directed the Senate Committee on State Affairs to study ways to ensure landowners were being compensated fairly. At a three-hour hearing in March, senators discussed requiring the company to pay for legal fees should a court award compensation at least 20 percent higher than the company’s initial offer. Such a requirement might disincentivize companies from lowballing landowners. Committee members also considered requiring companies to compensate for the decrease in value to the surrounding land as a result of the taking.

Some committee members acknowledged that eminent domain is a “necessary evil” and that although laws to provide fair compensation could strengthen a landowner’s position in negotiations, they could never truly level the playing field. For Spriggs, the solution is simple: “Give us the same legal rights as the company.”