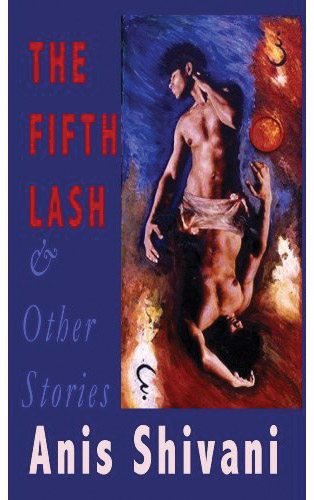

Beyond Suburbia: The Fifth Lash & Other Stories By Anis Shivani

A version of this story ran in the December 2012 issue.

As a literary critic, Anis Shivani has become notorious for lamenting the feeble state of contemporary American fiction. Today’s writers, Shivani argues, rather than confronting the political and cultural questions underpinning all of human experience, rely on flowery language, formulaic narrative, and plots driven by personal wounds and insular grief. “There is only small writing, with small concerns, and small ambitions,” he writes in his 2011 collection of criticism, Against the Workshop. Where are the Flannery O’Connors of today, the Cheevers of our time?

As a literary critic, Anis Shivani has become notorious for lamenting the feeble state of contemporary American fiction. Today’s writers, Shivani argues, rather than confronting the political and cultural questions underpinning all of human experience, rely on flowery language, formulaic narrative, and plots driven by personal wounds and insular grief. “There is only small writing, with small concerns, and small ambitions,” he writes in his 2011 collection of criticism, Against the Workshop. Where are the Flannery O’Connors of today, the Cheevers of our time?

Perhaps in answer to his own assessment, Shivani’s new collection, The Fifth Lash & Other Stories, situates its characters within sociopolitical landscapes that figure far more prominently than their homes, offices, and neighborhoods. Ranging in time and space from 1980s Pakistan to post-9/11 Southern California, these characters must wrestle with the confines of class distinction, marriage and senseless bureaucracy.

Tethered to these everyday fixtures in Shivani’s fictional world are the monolithic mechanisms of Islamic law, regime change, and media-manufactured deception, all of which leave his characters in varying states of paralysis, delusion, or resignation. In “Abscess of the World,” for example, a Princeton student visiting Pakistan finds in the shop clerks and street cops a collective “stoicism born from weariness.”

In “Love in a Time of Communication,” a young man in Karachi, Pakistan, battles the endless waits and labyrinthine administration of the local telephone exchange, paying repeated bribes and dubious fees to win a landline for his aging parents. Despite the depravity of the office, the protagonist, Javed, happens upon a woman with whom he can imagine a romance, and suddenly the possibility of a telephone becomes a path toward intimacy. But Javed wins only half the battle, which is to say he loses entirely. He secures a phone line the agency won’t activate, and he shares lunch with the young woman’s uncle, only to never see her again.

Javed makes a final plea to the phone company only to discover a staff change will indefinitely delay his technological ascendancy. Finally, he leaves the office too defeated to even pity the throngs stuck in line.

Much of The Fifth Lash follows the lives of Muslims, some more devout than others, but all of them trying—whether stationed East or West—to negotiate loyalties, social misrepresentations, and personal desire. In “What It’s Like to Be a Stranger in Your Own Home,” we find Mo (short for Mohammed) wallowing in his suburban New Jersey home after he and his wife have separated. In the wake of the September 11 attacks, uncanny coincidence and newly minted American distrust prompt Mo to suspect himself of being a terrorist, when he of all people should know otherwise. By the story’s end, Mo becomes inexplicably self-possessed and defiant: “He was through with others trying to define him, for good or ill.” The conclusion is reassuring, but somewhat difficult to believe.

A handful of the collection’s protagonists are Americans eager to understand the intricacies of culture, capital and custom in South Asia, characters whose curiosities are either abandoned entirely or impossible to satisfy. The suggestion here is that nothing can fully explain the gulf between East and West; neither earnest interest nor intellectual rigor can unravel the mystery.

We certainly can’t accuse Shivani of the same allegations he’s leveled against an emerging generation of writers. By leaping unabashedly into the contradictions and ironies of politics, Shivani sets himself apart from what he’s deemed a “homogenous crowd” that plays it safe at the expense of “meaningful ideas.”

Unfortunately, Shivani may have tipped the scales too far. In many of these stories, the settings seem more abstractly political than physical. Organizing systems take precedence over people, becoming oversized stages for characters more plastic than human, more like shadows than full-bodied citizens of the world.

Maybe that’s Shivani’s point, but The Fifth Lash fails to provide the visceral experience we demand of fiction. Too often the case is stated too plainly, too directly, and under too many floodlights, as when the fictional assistant to former Pakistani prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto declares, “The eighties are shaping up to be a long night of misery,” or, “I’m convinced the martial law regime has lost its head.”

We should no doubt applaud Shivani for daring to craft fiction that carries us beyond the usual domestic suspects—suburban boredom or over-privileged angst—and we know him to be an accomplished writer: The Fifth Lash is his fourth book, and his criticism has appeared in dozens of publications (including the Observer). But The Fifth Lash leaves its readers feeling as uncertain as the characters, and it’s unclear whether this is the intended result. At times the stories seem to ask for our empathy, only to then distance us with heavy-handed pronouncements and a noticeable lack of heart.