Bang for the Buck

Go Down Together:The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde

Bonnie Parker’s and Clyde Barrow’s violent 1932-34 crime spree through the Midwest tracked like a hurricane spiral stuck in replay, with the pair punctuating robberies and bloody escapes with faithful returns to visit family in Texas, disregarding their notoriety and a network of watchful lawmen.

On May 23, 1934, the cycle came to its gruesome end on a logging road outside of Gibsland, La. Six heavily armed officers, tipped off by one of the duo’s colleagues, opened fire, shooting the lovers and their stolen Ford all to hell.

Bonnie, a fledgling poet with a flair for drama, had predicted their legend in a poem titled “The Story of Bonnie and Clyde (The Trail’s End).”

Some day they’ll go down together; And they’ll bury them side by side,To few it’ll be grief—To the law a relief—But it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.

Three-quarters of a century later, Bonnie and Clyde remain the most infamous, doomed couple of the Depression era, and perhaps in American history, in no small part because of the 1967 film Bonnie & Clyde, whose charismatic titular outlaws, played with high-caliber sex appeal by Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty, struck a chord with American youth in an age of revolt.

Forty-two years later, the film has taken on the glam veneer of legend, so two new books marking the 75th anniversary of Bonnie and Clyde’s deaths offer a welcome corrective. Even the stars seem aligned for a revisit. As in the Great Depression, millions today find themselves, like our anti-heroes, jobless, foreclosed and wildly unsympathetic to bankers.

In Bonnie and Clyde: The Lives Behind the Legend, Schneider uses a risky, novelistic approach to put readers behind the wheel of the getaway car. The present-tense narrative slips into period vernacular. Writing about Barrow, Paul Schneider often shifts to second person: “You have the gun Bonnie smuggled into the jail cell, but it’s not doing you much good while you’re hiding in the crawl space under a house on some back street of Middletown, Ohio, hoping the police will give up on looking for you.”

Making liberal use of letters, memoirs, interviews and other source material, the book is studded with dramatic re-creations in jails, hideouts and motel rooms, wherein Schneider stages conversations and peppers the narrative with quotations like interview bites in a Ken Burns documentary. What works on television can seem pointless on the page. Relying on an interview with Marie Barrow on her brother’s affair with Bonnie, Schneider finally cuts to the crux with, “He loved her and she loved him.” The point hardly needs hammering.

Schneider excels, however, in setting scenes. His portrait of West Dallas, where the Barrows moved in the early 1920s, is one of heartbreaking squalor, a tent city like something imported from the Third World. Clyde’s mother, Cumie Barrow, a fire-and-brimstone Christian, loved her boys unconditionally. His father, Henry, was a failed farmer who found his groove running a gas station in West Dallas. As teenagers, Clyde and older brother Buck found their own grooves in petty crime, stealing bikes and chickens, moving on to car theft and armed robbery.

Clyde had experienced his first serious brush with the law when he failed to return a rented car he’d used to visit his girlfriend. As Schneider tells it, Clyde faced constant police harassment thereafter. Every time he got a regular job, he’d get fired after the cops showed up to question him as a suspect, or just for the hell of it.

Schneider devotes a good portion of his book to Clyde’s early criminal career, leading up through his early relationship with Bonnie, a former drama student whose social ambitions had been dashed by family tragedy, and his first trip to prison with a 14-year sentence. Eventually the minutiae piles up in a tangle, and the book begins to feel padded for effect. Schneider strives to create suspense, as when Bonnie’s letters to Clyde at Eastham Prison Farm dry up. Has his 19-year-old beau abandoned him? We know better than that; we’ve all seen the movie.

Conditions at Eastham Prison Farm were inhumane, and the discipline so medieval one expects to find Dick Cheney in the shadows taking notes. There Clyde murdered a tormentor, a sadistic prison guard who raped him, and secured an early release by having a friend chop off two of his toes. According to Schneider, such intentional mutilation was common. One year in Eastham was more than enough to make Clyde swear revenge on the prison system. He promised several fellow inmates to stage a raid and break them out.

Schneider’s book actually begins with a flash forward to the Eastham raid, carried out by Bonnie, Clyde and several accomplices on Jan. 16, 1934. One prison guard was killed, and several prisoners escaped with the gang. It’s an exciting sequence, with machine guns rat-a-tat-tatting through the daring escape.

That raid not only hastened the end for Bonnie and Clyde, but shined an unflattering light on Clyde’s transformation from a slacker delinquent with criminal tendencies to a hell-bent, full-throttle desperado. Though Clyde did fulfill his promise to raid the prison and free some pals, it took him three years. In the interim, he and Bonnie were too busy robbing banks, gas stations and small stores to keep his word.

They didn’t rob many banks. Mostly it was small stores and gas stations, many not very different from the one Clyde’s father ran. Sometimes their owners, not very different from Clyde’s father, ended up dead. The people who paid most dearly for Clyde’s rage often had nothing to do with the prison system. They were civilians of modest means.

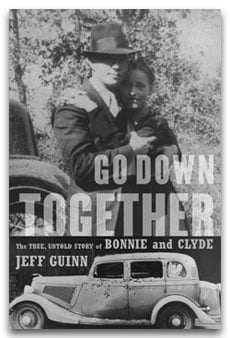

Jeff Guinn begins Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde on Highway 114 at Grapevine, Texas, on Easter Sunday in 1934. H.D. Murphy, a 24-year-old motorcycle cop on his first patrol, was to be married in 12 days. His fiancée had just picked out her wedding dress. Murphy and partner E.B. Wheeler pulled off the highway to check on what appeared to be a motorist with car trouble.

Clyde and cohort Henry Methvin got out of the car. Bonnie stayed put. Clyde said, “Let’s take ’em,” presumably meaning “for a ride.” Methvin, not one of the sharpest knives in the drawer, misunderstood and shot Wheeler at point-blank range. Clyde began cursing Methvin, but seeing no alternative, wounded Murphy with a single shot. Methvin finished him off with three more.

The murder of a young, about-to-be married patrolman turned public sentiment against the outlaws, but as Guinn points out, the writing was already on the wall. A month after the Eastham raid, a special commission had arranged for notorious former Texas Ranger Captain Frank Hamer to hunt down and kill Bonnie and Clyde.

The decision was justified on grounds that the Eastham attack was “a national embarrassment.” The lives of gas station attendants and store owners apparently didn’t rate as highly as that of a prison guard.

Each author expresses the lyricism and dark humor of Bonnie and Clyde in his own way. Though his style is more stripped down, Guinn knows how to milk weird comedy from desperate situations. Both do a fine job of describing complex shoot-outs and escapes. Both accounts underscore the layers of irony beneath Henry Methvin’s cooperation with the Hamer posse in setting up the ambush at Gibsland. Methvin was not only the trigger-happy bozo who killed patrolman Wheeler, he was one of the thugs Bonnie and Clyde broke out of jail at Eastham.

It’s an ugly truth that a life of crime often sticks you with really sorry company.

Schneider, the author more sympathetic to his subjects, does an equally good job of removing any tint of glamour from a couple who spent much of their time on the run, dressing oozing wounds, sleeping in cars and pooping in the woods. Guinn claims Bonnie was plain looking, certainly no Faye Dunaway. Schneider insists that photos don’t do her justice. While the best-known images show her smoking a cigar and playing with guns, that was apparently just for show. Former gang members said she never shot anyone, though “she was a hell of a loader.”

Despite differences in style and tone, both books have much to offer. If I could only buy one, I’d be sorely tempted to steal the other.

Jesse Sublett, a native Austinite, writer and musician, is the author of three crime novels, one crime memoir and more than 40 murder ballads.