Backs to the Future

At the Texas Republican Party’s convention in Fort Worth, it’s 2010 again.

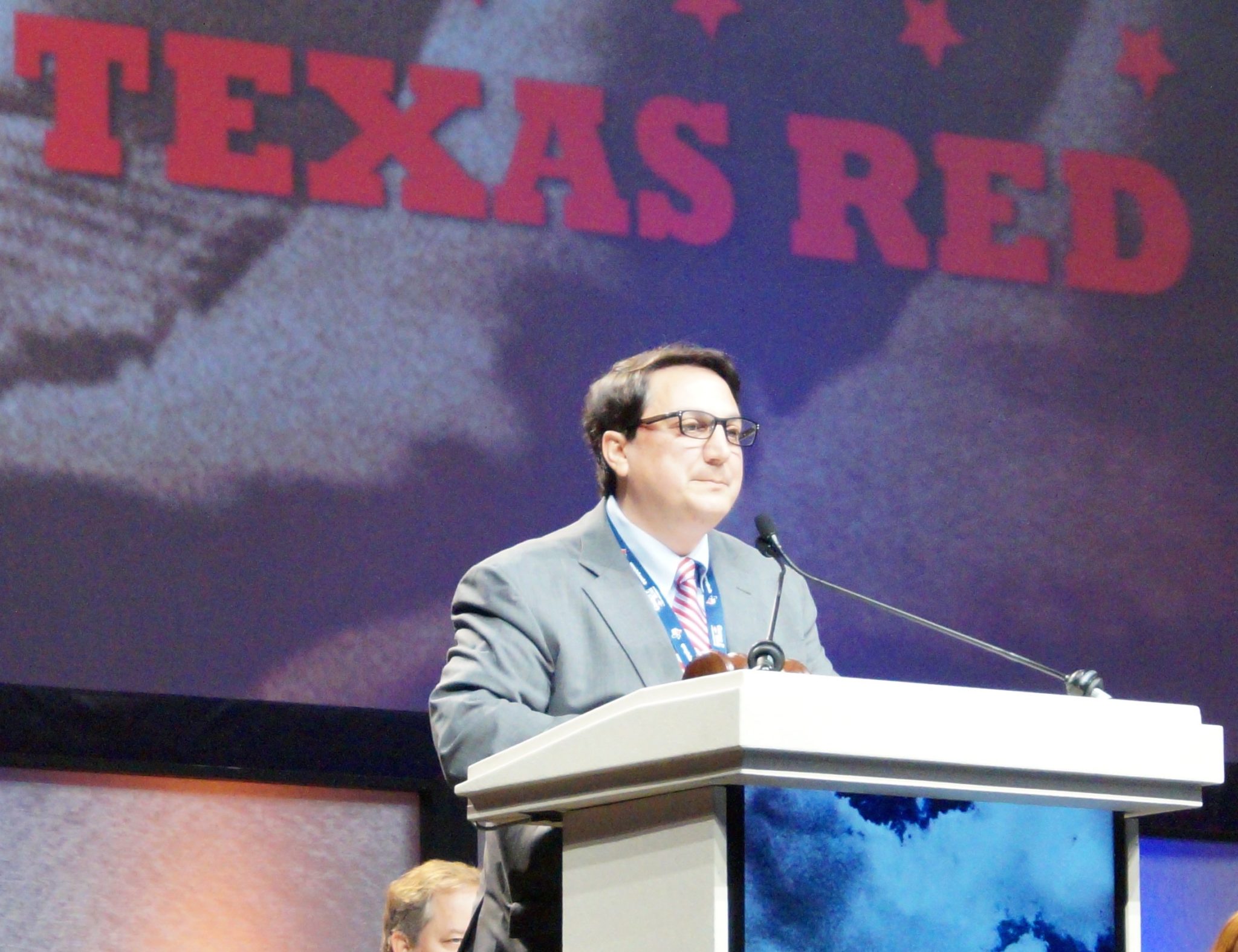

Above: Republican Party Chairman Steve Munisteri addresses the Republican Party of Texas' 2014 convention. June 7, 2014

Does the Republican Party of Texas need to become more “inclusive” for the sake of its electoral future? For many people, including a significant number of the party’s leaders and strategists, the answer is “yes.” For many of the party’s activist stalwarts, who gathered at the Fort Worth Convention Center this weekend to set the party’s course, the answer is emphatically, passionately, and angrily “no.”

The “Texas Solution,” the much-touted effort from the Republican Party of Texas to move toward acceptance of some kind of immigration reform, is dead. The measure, which was written into the party platform in 2012 and called for an expanded guest worker program, had been watered down in the convention’s drafting process—but it was replaced wholesale on the convention floor by hard-line immigration language that spells the end, for now, of one of the state party’s highest-profile dalliances with reform.

The new language emphasizes cracking down on immigration, calls for the end of in-state tuition as well as a raft of other measures, and waters down the guest worker provisions into almost total insignificance. “Once the borders are verifiably secure,” the plank reads, “and E-Verify system use is fully enforced, [the party calls for] creation of a visa classification for non-specialty industries which have determined actual and persistent labor shortages.”

The Republican Party now has, effectively, the immigration platform it had in 2010, the peak tea party year. It’s a remarkable reversal for several reasons. The Texas Solution’s inclusion in the party platform in 2012 was highly contentious among delegates at the time, but it was just as highly touted by party elders who wanted to show the GOP was evolving on an issue central to the future of a state with an increasing number of Hispanic voters—and a continuing need for a steady supply of labor.

But Land Commissioner Jerry Patterson, who was the most significant backer of the Texas Solution in 2012, was absent this year—shying away from the convention after an incredibly contentious lieutenant governor primary in which he backed David Dewhurst. In his place this year was ascendant lt. governor nominee Dan Patrick, whose tough-on-immigration campaign helped make today’s result inevitable.

Behind the scenes, Patrick and the GOP nominee for governor Attorney General Greg Abbott, had tried to weaken the immigration plank in the run-up to the floor fight to make it more acceptable to the base. But that gambit failed. The new plank contains language taken more or less directly from Dan Patrick’s campaign website. The heated rhetoric candidates use in primaries has consequences.

The platform is a statement of principles, and no more. But these principles happen to be Dan Patrick’s principles. The Republican Party of Texas’ 2014 platform calls for the abolition of “sanctuary cities,” and the abolition of in-state tuition for undocumented immigrants—a measure Republicans passed through the Legislature just a few years ago. The Republican consensus is shifting, and the platform fight is a preview of what the Legislature could look like under Lt. Gov Dan Patrick, who, come November, could lead a Texas Senate drifting significantly further to the right.

Only one other issue made it to the floor Saturday afternoon: medical marijuana. The party had flirted with endorsing medical pot during the platform drafting process earlier in the week, but eventually stripped it out. Some activists succeeded in pushing it to the floor, but delegates voted the efforts down. The issue’s appearance at the convention at all was a victory for the pro-medical marijuana crowd, who won a surprising degree of support.

But if that showed incremental progress, consider what didn’t make it to the floor. Consider also that it’s 2014. The new Republican Party of Texas platform endorses what’s known as “reparative therapy,” the practice of training LGBT people to “convert” to heterosexuality. The platform committees dropped some archaic anti-gay language, but added a provision recognizing the “the value of counseling which offers reparative therapy and treatment to patients who are seeking escape from the homosexual lifestyle.”

Delegates who objected to the language wrote amendments attempting to alter it, but they never got a chance to introduce them on the floor. Debate over the platform was ended after five hours, and pro-gay Republicans were out of luck.

“I want every Republican elected. I’m here today trying to get Republicans elected,” said Rudy Oeftering, a vice president of the Texas Log Cabin Republicans, a gay GOP group that had been banned from having a booth at the convention’s trade shows. But he admonished reporters on the convention floor to keep focus on the plank, even if the state party didn’t feel like talking about it.

“Every reporter should be asking every Republican candidate if they believe in reparative therapy. If they believe that homosexuality is a choice,” he said. “If you’re going to put language like this in the platform to drive away voters, then every Republican candidate should be accountable for what’s in the platform. The platform itself says that every candidate needs to take a position on this.”

There was one other thing the GOP got around to before adjourning—deleting a four word sentence in support of “net neutrality,” an effort seeking to ensure internet providers to charge the same amount for all internet traffic. Net neutrality is a complex issue, but it basically pits internet providers and their shareholders against internet users and web companies like Google and Netflix .

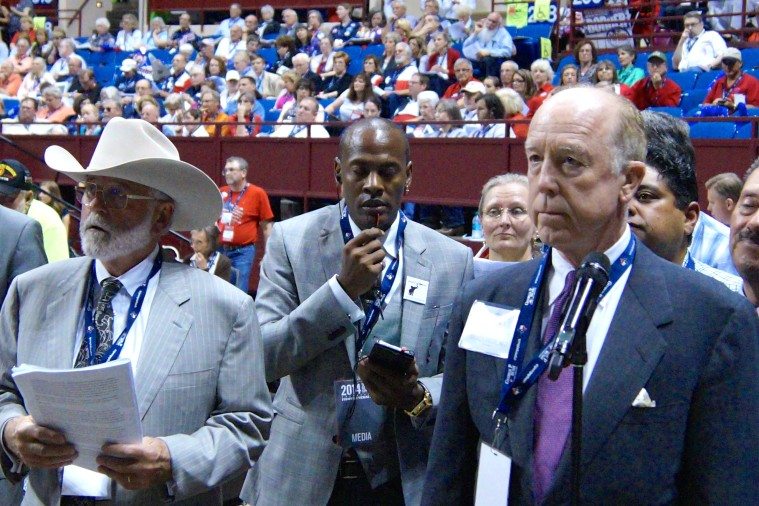

Delegates had been explicitly banned from introducing amendments on the floor—they were supposed to be in at 6pm the previous night—but when Congressman Randy Weber ambled to a back mike with four state reps. by his side, including Bryan Hughes and Steve Toth, Republican Party Chairman Steve Munisteri proposed the convention make a special allowance for the officeholders to propose an amendment. They were the only officeholders to speak on the platform all day.

Weber pointed to the sentence endorsing net neutrality. “I don’t know how the hell that got in there,” he said. (Presumably, because Republican delegates on the platform committee wrote it in.) Weber handed the show off to state Rep. Hughes, who told the crowd: “If you love Obamacare, you’ll love net neutrality,” he said.

There was a very brief debate, and the delegates quickly acquiesced to the special request from the legislators and congressman. Verizon and Time Warner Cable, both internet providers resolutely set against net neutrality, were major sponsors of the convention.

So on immigration, the GOP returns to 2010—and we now know that the last-minute wishes of telecommunications companies are more important to the party than the very existence and identities of gay people. What an election year 2014 has been—and it’s just starting.