Author Reyna Grande on Immigration, and Telling Her Own Story

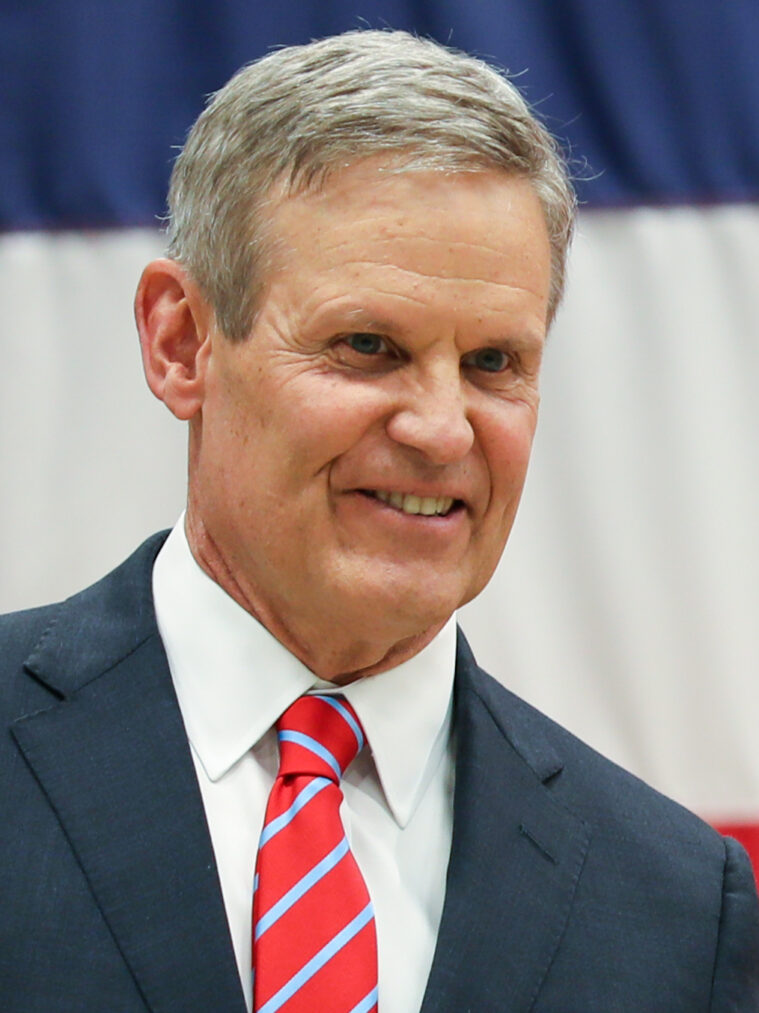

Above: Author Reyna Grande

“At first it was about me wanting to write something for me,” author Reyna Grande says of her 2013 memoir, The Distance Between Us. The book, which tells the story of Grande’s illegal immigration to the United States from Mexico in 1985, began as an attempt to come to terms with her own family history, and eventually evolved beyond the purely personal. “I hear from immigrants who will say, ‘You told my story. That’s what happened to me too.’”

Grande will speak at UT-San Antonio as a part of the university’s Creative Writing Reading Series on Friday at 7:30 p.m.

The Distance Between Us is Grande’s third book, and first nonfiction work. She won the American Book Award and Premio Aztlan Literary Award for her first novel, Across a Hundred Mountains, which told a fictional story very similar to her own. When Grande was two years old, her father left her family for the U.S. Two years later her mother followed, leaving Grande and her siblings with their grandmother. Grande would later make the same journey herself, when she was nine years old, but she traces her first novelistic inklings to that time spent at her grandmother’s house in Mexico: “We didn’t have a television at my grandma’s house so we listened to the radio, and every night they would have story time, and I just remember how listening to all the stories really helped me to understand why things were happening in the world around me—and I learned to turn to stories for that. To understand.”

After immigrating, Grande and her siblings reunited with their parents in California, and she’s lived in the Sunshine State ever since. She and her family are scattered around Los Angeles, where Grande, now married with two children, teaches creative writing at UCLA. Writing has always been personal for her, a way to make sense of how her parents abandoned her, and how even after they were reunited those ties remained broken.

For her next book, though, Grande is looking for a story outside of herself, one that doesn’t hurt so much to write. “After I finished the memoir I was so emotionally depleted that I didn’t have any more stories,” she says. “I felt I had just emptied myself out and I had nothing left, and it’s taken me about a year and a half to finally start writing again. And I’m writing fiction now. The story has nothing to do with me.”

It does still have to do with immigration, though, but this time in a historical context. The novel-in-progress is about Irish immigrants who, during the Mexican-American War, deserted the U.S. military to fight for Mexico. “I’m still writing about U.S.-Mexico relations, about the immigrant experience—crossing borders in a way,” Grande says. “But it’s actually been kind of nice to not have to write about myself anymore. It gives me a chance to heal since I don’t have to cut my wrists open and bleed all over the page anymore.”

As emotionally draining as writing her memoir was, Grande says she receives emails constantly from people thanking her for helping them to understand their own immigration experiences more intimately. It’s a response she doesn’t take for granted. “A lot of books about immigration are from third parties who are researching the topic, and they’re interviewing immigrants to write their experiences down, but it’s very rare when that immigrant gets to tell that story herself without having somebody else tell it for her,” Grande says. “That’s what I’m really grateful for—that I can use my own voice to tell my own story. I wish more immigrants had that opportunity.”

Grande returns with her children to Mexico every few years to visit family, but she says she finds the experience is bittersweet. The same lifestyle that enables Grande to visit Mexico distances her from relatives still living there, who are rarely, if ever, able to travel. “When I go to Mexico I’m treated like an outsider, and that’s hurtful, because I realize that people don’t really see me as Mexican anymore,” Grande says. “When I speak Spanish, I speak it with an American accent.”

Grande earned her B.A. in creative writing at the University of California-Santa Cruz. The love of stories that began with listening to the radio in her grandmother’s house in Mexico grew into the ambition of writing stories of her own when Grande saw author Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston speak at UC. “I just remember how overwhelming it was to actually see a real author in person and to realize, oh, they’re real people. These are real people writing books.”

Later, while attending Antioch University’s MFA program, Grande was the only Latina student in many of her creative-writing classes, where she was often told her prose was overly dramatic. “Most of the students were writing stories about going to parties, doing drugs, drinking, that kind of stuff. And then I was writing stories about walking to school barefoot in Mexico because we didn’t have money for shoes,” Grande remembers. “I was writing about my reality, which was very different from their reality, and my teachers would always say I was so melodramatic, that I had a wild imagination. They would tell me my writing was ‘overwritten,’ over the top, full of cliches, flowery, and just a melodrama. And I wouldn’t understand that, because to me this is not a melodrama, this is what I went through.” Grande says she tries to keep that criticism in mind when dealing with her own students, and to encourage them to try new things. She tells them, “If it’s done right you can really do anything that you want in a story.”

Some of Grande’s favorite examples are Jamaica Kincaid’s The Autobiography of My Mother and Justin Torres’ We the Animals. “I like books that are very lyrical,” Grande says. “They’re just really simple and beautiful.”

Now, Grande frequently travels to university writing programs hoping to encourage young writers to put pen to paper, she says. “Watching Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, I understood how powerful it can be to tell your story, because you can connect with people through it. It took something that was abstract and made it concrete.”