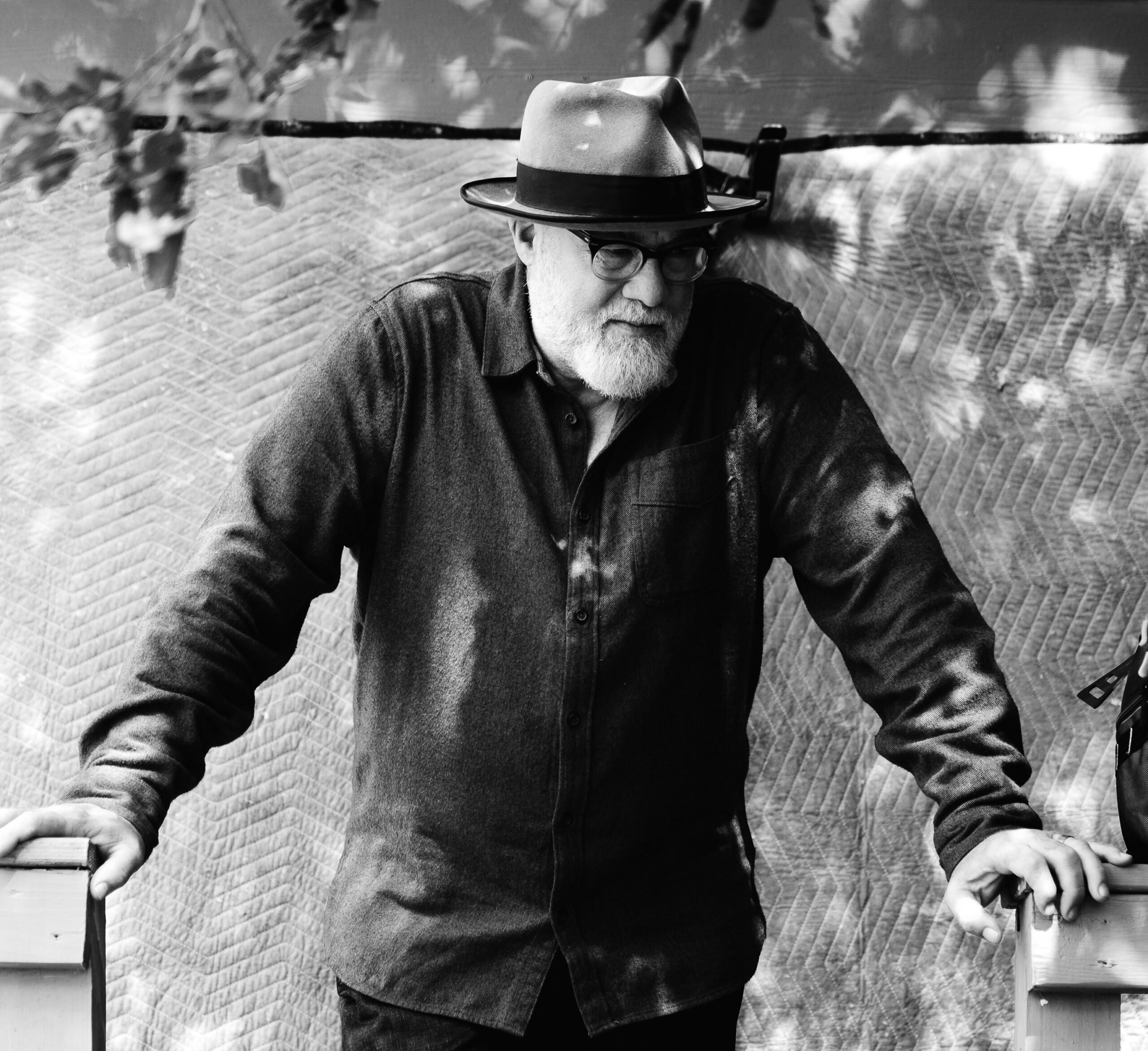

Austin Filmmaker Bob Byington Has Crafted a Universe of Comic Misanthropy

A version of this story ran in the April 2015 issue.

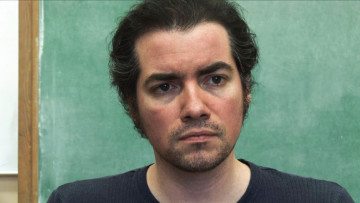

Above: Jason Schwartzman in 7 Chinese Brothers.

I have a friend who would happily watch a two-hour industrial film about warehouse safety if Wes Anderson directed it. That’s how deeply he’s convinced that the director’s vocabulary was created to speak to him especially. Every slow-motion scene set to a song from the ’60s, every fussy bit of dollhouse set design, every delicately composed static shot, every whooshing horizontal tracking shot, every deadpan exchange: My friend believes it’s his language Anderson is speaking. Even regarding the films he can admit are misfires, his devotion remains intact. His love is unconditional. It transcends petty distinctions between good and bad.

There may be fewer of us who see and hear in Bob Byington’s cinematic language that same sort of very personal familiarity, that sense of connectedness, but we exist. We’re a small cult, but an avid one.

Over the last decade, as Robert Rodriguez, Richard Linklater and the Duplass brothers have risen to Hollywood’s heights, their fellow Austinite Byington has remained just to the side of success, quietly shooting four features over the last seven years. He’s a marginal figure revered by those who’ve discovered him, but not quite able or willing to break into the mainstream. To fans, this obscurity is part of Byington’s appeal. We feel like we’re in on a secret.

To fans, obscurity is part of Byington’s appeal. We feel like we’re in on a secret.

Larry, the hero of Byington’s latest feature, 7 Chinese Brothers, which had its world premiere last month at South by Southwest, is no different. Larry, played by Jason Schwartzman, is the perfect embodiment of the Byington protagonist: mocking, mordant and full of biting contempt for the world. Fired from his job at a chain Italian restaurant for stealing and boozing, Larry starts working at a nearby lube shop, where he shows his affection for his new boss the only way he knows how: by ceaselessly antagonizing her. He’s the same with his best friend, his co-workers, even his grandmother.

Arguably the most cynical of Byington’s films, 7 Chinese Brothers is a character study of a young man in a slow collapse of his own making. To Larry, social conventions are lies best lampooned or ignored—so what if they lead to compassion or intimacy or human connection? He dismisses everything that everyone else holds dear: work, sex, money, family, tradition. But his attacks are just masks for depression, a thousand and one mirrors deflecting light and love.

It takes a particular talent and a special aesthetic conviction to devise your own language as a filmmaker and to call on that language in every one of your films, so that each is unmistakably yours. As a movie fan, there’s nothing quite as rewarding as entering the world of an artist who has accomplished this, who owns a distinctive voice that gets richer and more varied with each film. Bob Byington, quietly, and mostly under Hollywood’s radar, has spent the last decade constructing a universe of comic misanthropy that could be mistaken for no one else’s.