The New Prosperity Gospel

At the group's convention in Dallas, Americans For Prosperity showed us—just maybe—the future of American conservatism.

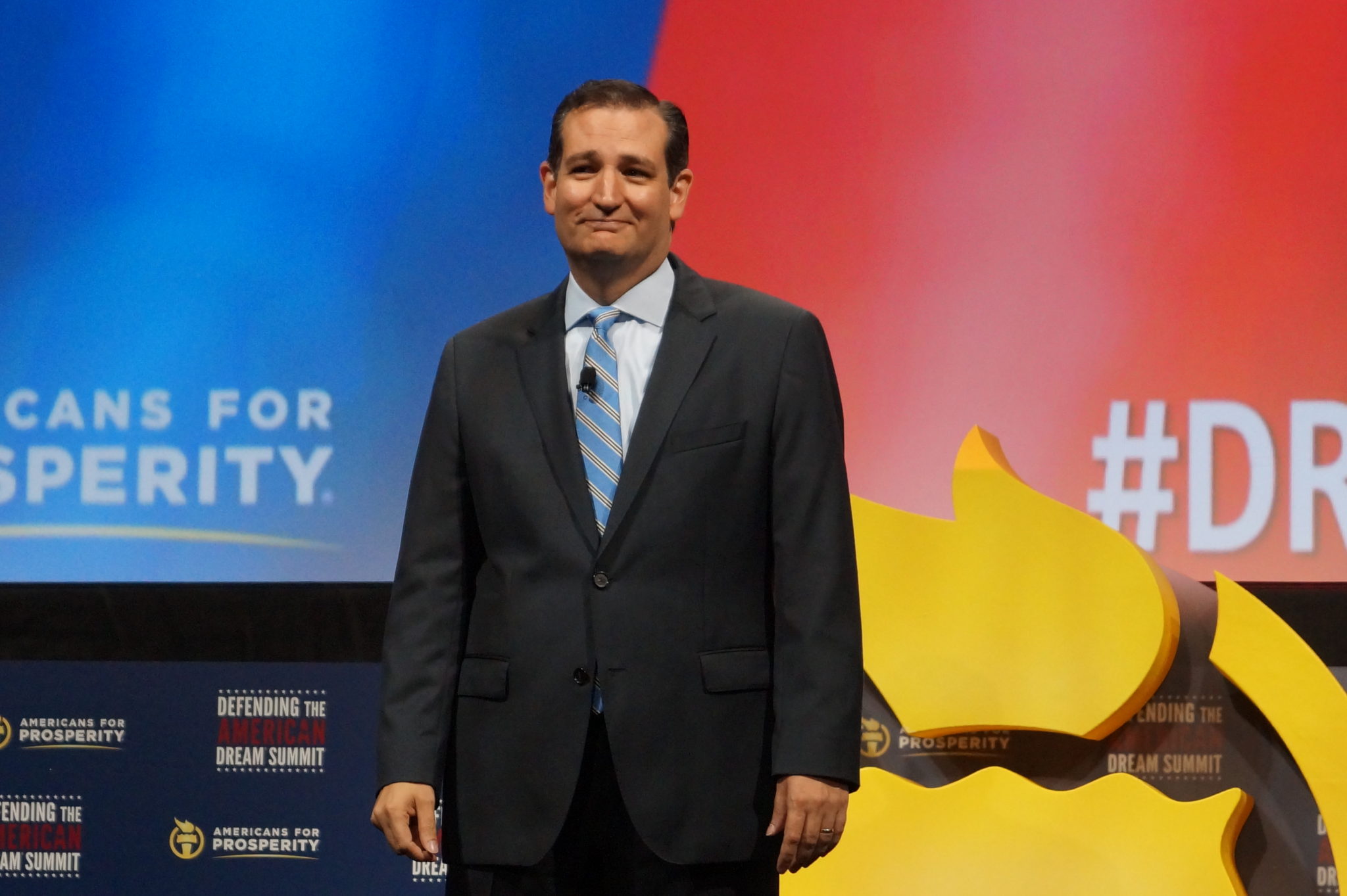

Above: Texas Sen. Ted Cruz speaks to a rapturous crowd on the second day of an Americans For Prosperity summit in Dallas.

The hundred or so conservative activists convened in the ballroom of Dallas’ Omni hotel are in for a real treat: A sneak-peek of the last chapter of the troubled trilogy adaptation of Ayn Rand’s law-library length magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged.

The trilogy—part of a years-long effort to create a Rand revival that started just after Obama’s inauguration—has had a rough go. The first two chapters were commercial failures that seemed to encapsulate a recent feature of American political life—the blustering revival of reactionary forces and their as-yet failure to turn rage and disgust into electoral or cultural success. The third was reduced to finding funds on Kickstarter—a bit like looking for change in your parents’ couch. But at this screening, on the eve of Americans For Prosperity’s national convention in Dallas in late August, it feels, for just a few moments, as if the movement might finally be waking up.

On screen, John Galt, champion for the job-creating class, is tied and tortured by his statist captors in the position of Jesus of Nazareth on the cross. Rescued by Dagny Taggart and spirited to a waiting helicopter, the two watch society collapse around them. Stock footage of cities losing electricity cycles on screen. As the Makers escape, the great collectives of the Takers, layabouts and leeches enters a death spiral.

“It’s the end,” says Taggart. “No,” says Galt. “It’s the beginning.” Cut to the Statue of Liberty, which remains lit. Fin.

Galt preached withdrawal (though not in his relationship with Taggart—more on that later.) Like a Sufi mystic, he urged others to turn away from a corrupt world and perfect themselves. It’s an incongruous message to kick off this summit. AFP’s goal is the polar opposite—the group’s faithful are uncompromising evangelizers, and their position within the conservative movement is growing. Their goal is to transform the country, stripping government to the bone and empowering men like Charles and David Koch, AFP’s conglomerate-inheriting founders, who hate taxes, regulation and environmental safeguards. The nation as Galt’s Gulch.

Americans For Prosperity dates to 2004, but since the rise of the tea party movement, it’s quickly become one of the conservative coalition’s most important organizing engines. There are several reasons why. There’s money, of course—AFP has access to a lot of it. The Kochs, through organizations which include AFP, have funded almost 44,000 TV ads this election cycle, and that’s only through the end of August.

The organization hosts plenty of star power—GOPers eagerly line up to receive the AFP blessing. Gov. Rick Perry, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz and Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul all had prime speaking slots at this year’s summit, while other Republican notables simply came to pay their respects, from Indiana governor and future 2016 also-ran Mike Pence, through Texas lt. governor nominee Dan Patrick, all the way down to state Rep. Bill Zedler.

But to keep empire-building, the group needs to be constantly attracting conservative grassroots to the cause, many of whom may have different core concerns than AFP—like social issues, or foreign policy. This is the second annual Defending the American Dream summit, in which the group convenes activists from around the United States, some who came up through tea party groups that have lost a bit of steam, with the aim of imbuing them with the one true religion—to mold them, teach them, and make them effective organizers under the big umbrella of the Koch’s advocacy network.

Above all, though, the summit is half sales pitch, half religious revival. AFP’s product—the one it’s turning conservatives grassroots into pitchmen for—is the new prosperity gospel, a quasi-religious belief in the ability of the free market to solve social problems. All social problems. And make you rich, too.

There are two types of attendees at these conferences. There are the Organizers, often young and slick, who wear well-fitting suits and have done time in Washington, D.C. Then there are the Grassroots, who wear flag paraphernalia and hail from all corners of the heartland. The Organizers get their swank hotel stays comped—the Grassroots pay hundreds of dollars to come and stand in the same room as the powerful.

Here’s how the relationship works: The Grassroots exude a substance called “influence,” which can be harvested and put to work by the Organizers. The suited figures cannot influence Congress and push their legislation in far-flung state capitols without the influence harvested from the flag-pin wearers. At the same time, without the overseers, the down-home crowd has very little real power—much, much less than they think they do.

None of that’s to say that this is an entirely cynical or utilitarian relationship—that’s not how ideology works. There may be perfect unity of thought. At one of the conference’s afternoon sessions, Teresa Oelke, a vice president and director of state operations for AFP, ran through a list of the organization’s many accomplishments—quashing tax increases, beating back regulation, fighting increased availability of medical care for the poor. “We couldn’t do this without you,” she told the crowd, to riotous applause.

So a great deal of effort is expended at these confabs to groom the Grassroots, in order to make them more effective proxies for the ringleaders of the I-95 corridor. This can take several forms. AFP helped train attendees in social media basics: “They got me to open up a Twitter account,” said Stephen Eldridge of Cosby, Tennessee, who also learned tricks to use on Facebook.

But many of the workshops had to do with messaging—the tough question of how to bring the message of Liberty to unwilling and uncooperative audiences, like minorities, young people and women. One panel, the evocatively titled “Thanksgiving Gone Wrong: How to Talk About Freedom,” included sage words from Anita MonCrief, a former ACORN organizer who saw the light, and forthright talk from Daniel Garza, a Clark Kent look-alike with the Hispanic-oriented LIBRE Initiative.

Listen with an open heart and mind. Be warm and friendly. Understand, and empathize. Stridency can alienate. At the same time, don’t be afraid to start that conversation. MonCrief called the protests in Ferguson a “missed opportunity” for the conservative movement: It alienated people when it could have showed them it cared. Garza chided the crowd: “Conservatives think that the idea of liberty sells itself. That you don’t have to communicate those ideas to minorities.” They had ceded ground needlessly.

Audience members listened—then they took the mic and talked about … whatever they wanted to talk about. One asked MonCrief about how best to “teach” black communities—always an odd word choice over “persuade,” but frequently used at the summit. “It appears we are losing the battle with our children,” one said. “Even the American Indian teaches their heritage.” Another: “There’s an ancient writing. It says: ‘Raise up a child in the way that he should go, and when he is old, he shall not depart from that way.’ With that in mind, I say: ‘Raise up a little socialist, and what do you get?’”

Another objected to the framing. “Can we look at freedom as something to market and to sell?” It was debasing. “Their vision of the future—they’re the student council weenies who outlaw frisbee on the beach, and their vision of the future is lines at the DMV, bread lines and then firing lines.” The room was anti-firing squad. The message of inclusivity, though, rubbed off on at least one attendee, a friendly older gentleman who, on his way out, filed past a young black man working a soundboard. “Great job,” he said encouragingly.

The insularity of this world, combined with the belief that they are in possession of an unimpeachably true and universal message, is hard to square. In all things, AFP tries to teach its flock the Jesuit’s patience. A video message played for attendees touts the story of John Todd, a local organizer from Wichita, Kansas, who tried to dialogue with an Occupy protest. There, he went along with the protest’s strange hand signals. He wiggled his fingers when he agreed with a statement at group meetings. For his patience and zeal, he was named a 2014 Americans For Prosperity activist of the year. (Later, by the elevators, he’s approached by friends who greet him with the wiggling fingers, and the whole crew breaks down in cackling laughter.)

American culture is a commercial culture, and the primacy of the marketplace is deeply embedded in American history and identity. What’s different about AFP’s ideological profile is that the worship of the marketplace is the only constituent element of an all-encompassing worldview. There are no other values on display: The lives of men and women are not determined by social factors or chance or tarnished by prejudice—there is only economics. It’s a curiously Marxist formulation.

Speakers here, like the American Enterprise Institute’s Arthur Brooks, rail against the idea of “dead-end jobs:” None exist. Instead, he says, the country has a “dead-end culture, dead-end government, and dead-end people.” Many attendees here proudly recall their first fast-food jobs—in the suburbs, before they went off to college. They can’t imagine that anyone has it any other way. They laud speakers who “made it” from unlikely and harsh circumstances: They love nothing more. They’re proof that it can be done. Others aren’t trying hard enough. Race, privilege, bad luck—none of these is of real importance.

Every one of the country’s current problems is “self-inflicted” by economic strictures. There are no weaknesses or insecurities or sins that the American people possess that cannot be filled or absolved by making it easier for the employer, employee and banker to circulate currency.

But that’s not the real reason for the power of AFP’s mythos. Have you ever seen Joel Osteen, or any of the countless faith-merchants who preach from the gospel of prosperity? Here’s their story: If you believe in God hard enough, if you turn away from sin, and if you put money in the pocket of your friendly neighborhood minister, you won’t just be rewarded just with spiritual solace, but also with earthly riches. It is, perhaps, the most American of religious traditions.

For the conference, the ballroom of the Omni was dressed just like a megachurch, minus the cross. A podium and a stage decorated with flowers stood flanked by gargantuan screens, in front of rows and rows of hotel-chair pews. Jennifer Stefano, the managing director of AFP who moonlights as a remarkably shouty cable news guest, opened the second day of speakers. Like a cheerleader at a pep rally, she paced the stage and rallied the troops until she was hoarse.

She wanted to live in an America where everybody earned their success, she told the crowd, and it would soon be possible. She was introducing Carly Fiorina, who once ran for the U.S. Senate in California, to just about the only crowd in America where that’s worth a standing O.

Fiorina, the former CEO of Hewlett-Packard, was proof of what could be achieved in this country if you believed, Stefano said. She came from a hardscrabble background, and became a titan of industry, where she experienced astonishing success, the crowd was told. (Conventional wisdom says Fiorina single-handedly tanked HP, but the less said about that the better.)

Fiorina opened with a lesson she learned from her mother. “What you are is God’s gift to you,” she related. “What you make of yourself is your gift to God.” When government stifled free enterprise, it was interfering in this most sacred transaction: Our gifts to the gods. Liberals, she said, “do not think everyone has potential,” and don’t think “everyone has the capacity to lead a life of dignity and purpose.”

Republicans would help the poor realize their potential, and imbue their lives with dignity and meaning. The poor could do this by getting a job. Then they would learn “self-respect,” she said. “When we conservatives say that a work requirement must be part of welfare reform, we’re not just trying to save money,” she intoned. “More importantly than that, we are trying to save lives.”

As the hall erupts with applause once again, I find myself thinking of the old hymn: Come, ye sinners, poor and needy…

Fiorina and the conference’s other speakers are the high priests of the new prosperity gospel. Among them are both Perry and Cruz, who spoke in the giant Omni ballroom on alternate days, as if to signal their impending political collision. As is tradition now at these events, Cruz was the main draw. Hundreds lined up well in advance to get good seats—he drew the loudest and most sustained applause. He remains the tea party godhead.

A substantial portion of Cruz’s speeches these days are one-liners that have accumulated in his repertoire over time. Here’s one: “I spent much of last week—last month, rather—in Washington, D.C. So it is great to be back in America.” Many in the crowd would have heard this line from him before, if not dozens of times, but they roared for it. Anything Cruz says is eligible for a standing ovation—“America should stand with Israel” won him 10 seconds of applause.

There was some new material—both Cruz and Perry are increasingly comfortable making foreign policy criticisms of Obama, though Cruz’s seem more intentionally ambiguous as to his own proposed policies. Perry seems set to make foreign policy a major emphasis of his run: We’ll see how that goes.

There was Ben Carson, who captivated the crowd in a speech that was more like the lecture of a beloved college professor, and Rand Paul, who gave a very explicitly partisan and anti-Hillary Clinton speech. Her handling of Benghazi disqualified her from the presidency. Awkwardly, he was played off the stage, rushed by loud music—to make time for … Tennessee Rep. Marsha Blackburn? A bit odd.

Their presence sanctifies this meeting, but AFP’s focus is on the long term, not the Iowa caucuses. A Republican might not stand a good chance of occupying the White House before 2021, when Democratic momentum is finally fully tapped. When that happens, AFP wants to be front and center, with its particular message dominant within the GOP. There are plenty of strains in the conservative coalition that sometimes sit ill at ease with each other—Christians, libertarians, hawks, isolationists. The free market’s psalms, AFP hopes, can bind them all together.

AFP wants to be a big tent, but the task of syncretizing conservative traditions and orienting different groups toward value-neutral free market advocacy could prove tough. For one, the world has already fallen far from the group’s ideals. In an irony that probably escaped the attention of most of the attendees, AFP’s free market-boosting convention took place inside a luxury hotel owned wholly by the city of Dallas. (Even in Rick Perry’s Texas, it seems, state capitalism is ascendent.)

Among the activist class, there’s a complicated, overlapping map of value systems at play. Take that first night’s screening. During the credits, producer Harmon Kaslow came out for a Q&A. Several had the same complaint: They loved Rand’s yearning for the collapse of American society, but the sex scene between Galt and Taggart turned stomachs.

A Louisiana tea party leader who identified himself as a member of the Christian right diplomatically suggested that the DVD come without the scene. Another woman from Virginia, visibly distraught, told the producer she desperately wanted to show the movie to women’s groups. “Please take it out,” she said repeatedly.

Kaslow, resigned, told the crowd he’d heard it before. “That’s tame compared to what’s in the book,” he said. The missionary’s work is never done.