A Texas-Style Gun(less) Debate After a Year of Mass Shootings

In his zealous rejection of “red flag” laws, Dan Patrick reminds us of the long odds anything resembling gun reform faces in the Texas Legislature.

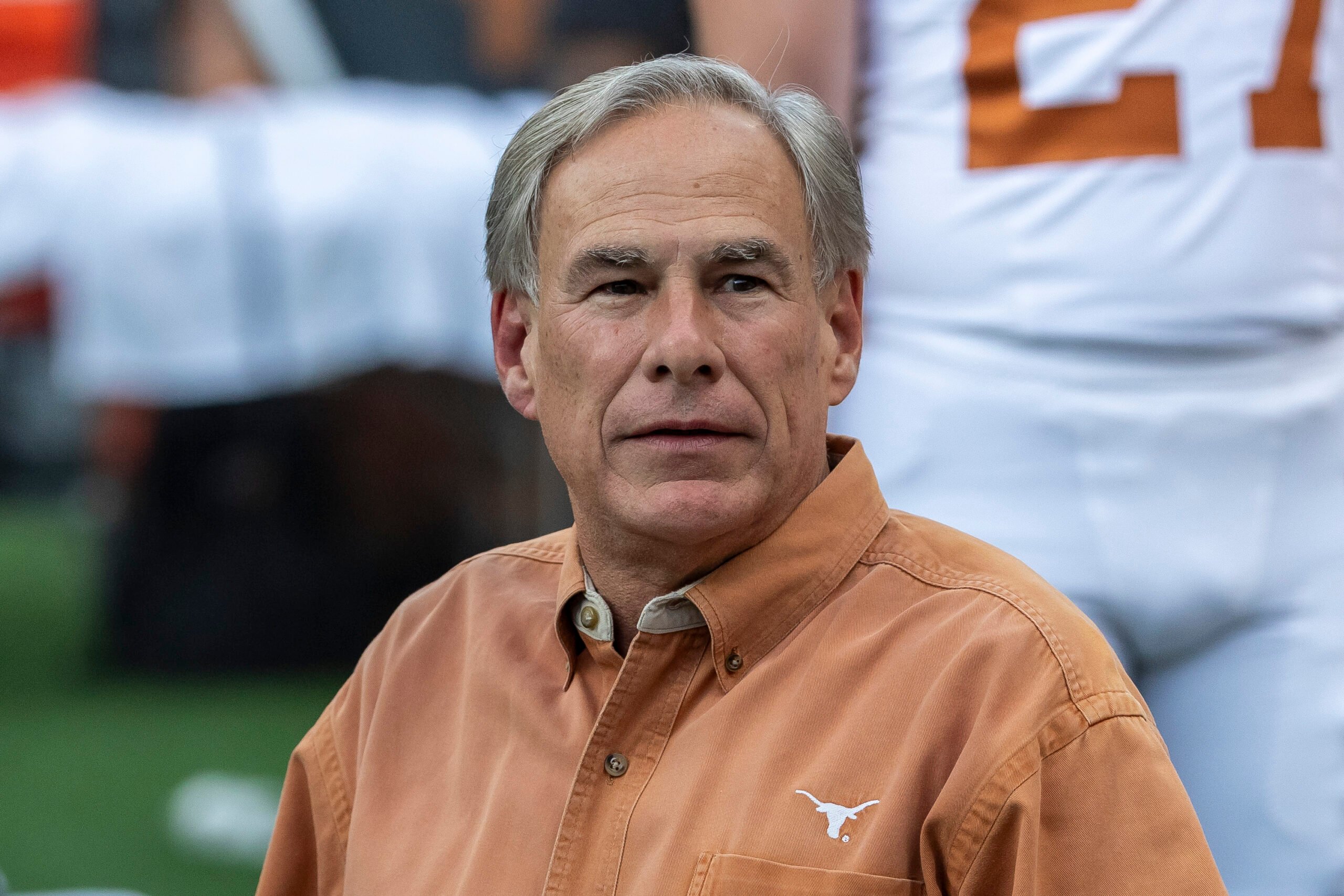

Above: Governor Greg Abbott, his wife, Cecilia, and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick prepare to place flowers at Santa Fe High School, where a gunman killed 10 people.

Texas remains hostile territory for even modest forms of gun reform, after a year punctuated by mass shootings.

In November, Governor Greg Abbott and other top GOP leaders bumbled through the state’s deadliest mass shooting in modern history by preaching about evil and dodging questions about guns. Their tone, however, began to shift after another mass shooting at Santa Fe High School six months later. Even Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick — who blamed mass shootings on abortion, too many doors and violent video games — called for hearings, demanded action and engaged in other serious-sounding talk about guns after Santa Fe.

Notably, Texas GOP leaders were even willing to entertain laws that looked, if not like gun control, at the very least gun control-adjacent. Abbott’s post-Santa Fe “School Safety and Firearms Action Plan” included a section asking the Legislature to explore new laws that would allow law enforcement to temporarily seize guns from someone a judge determines to be dangerous. And on June 1, Patrick tasked a special Texas Senate committee to study gun safety, including these so-called red flag laws.

Which isn’t to say Patrick or other Texas lawmakers necessarily support any new laws to confiscate guns. Despite the somewhat surprising early overtures, the culture war-waging gatekeeper of the Texas Senate disavowed red flag laws on Tuesday, even before the Senate committee he convened could issue its own recommendations. (Senators are expected to release their report on school safety sometime next month.)

Perhaps he was spooked by recent committee hearings. On Tuesday, a Second Amendment lawyer compared the proposal to “precrime” à la Minority Report. Gun-loving parents also turned out to warn lawmakers that any new gun restrictions would perpetuate, as one woman said, “the false premise that we can actually stop evil.”

After the hearing, Patrick said he only asked the upper chamber to consider red flag laws because Abbott proposed them first.

Patrick’s statement now desperately wants to distance himself from his own committee’s work:

“Regarding the topic of ‘Red Flag’ laws, which was discussed today in the select committee, I have never supported these policies, nor has the majority of the Texas Senate. A bill offered last session garnered little support. Governor Greg Abbott formally asked the Legislature to consider ‘Red Flag’ laws in May so I added them to the charges I gave to the select committee. However, Gov. Abbott has since said he doesn’t advocate ‘Red Flag’ laws.”

Tuesday’s hearing and Patrick’s reaction to it are a nauseating reminder of the long odds anything resembling gun reform faces in the Texas Legislature, despite back-to-back mass shootings this past year. Instead, the debate has largely coalesced around “school safety,” ranging from Patrick’s war on doors to other options such as arming school employees, buying metal detectors and cracking down on problem students. During one hearing last month, Senator Joan Huffman, a Houston Republican, wondered why school police don’t frisk every student they see wearing a long coat. Senator Eddie Lucio Jr., a long-standing Democratic lawmaker from the Rio Grande Valley, asked whether schools should send students accused of being disorderly to “bootcamp-style facilities.”

But many educators warned that not only would that kind of crackdown fail to curb school shootings, “zero tolerance” policies also carry serious consequences for kids. As we reported last week, the number of Texas students referred to law enforcement for threat-related charges has skyrocketed since the Parkland shooting. Like other forms of discipline, the recent spike in criminal referrals has swallowed a disproportionate number of African-American students. Disabled students also say that they’re being inappropriately charged with serious threat-related crimes based on misunderstandings or bullying related to their disabilities.

Take, for example, Nicolas, a nearly blind 12-year-old Houston ISD student who was charged with terroristic threat in March. A complaint filed with the Texas Education Agency by Nicolas’ mother (who asked that we only use her son’s last name to protect his privacy) claims school officials for years failed to accommodate his disability or stop the incessant bullying he faced because of his problems controlling his bladder and bowel movements. One of Nicolas’ student evaluations from last year reads, “He will often hide under the stairs and has once tried to leave the campus.”

The mother’s complaint states that on March 1, after Nicolas soiled himself at school, a bully announced it to the class. Shiloh Carter, a lawyer with Disability Rights Texas who helped the family file the complaint, says school officials accused Nicolas of threatening to kill the boy during the ensuing argument. Carter insists Nicolas was incapable of carrying out the threat, even if he had made it.

“This all could have been prevented,” Carter told the Observer. “Now it’s escalated to such a serious situation where he’s facing felony consequences.” Four days after the alleged threat, Nicolas returned to school without incident and police arrested him in front of his class, after which he spent a night in juvenile detention.

The Harris County DA’s Office, which is prosecuting the case, said it couldn’t comment, and representatives with Houston ISD wouldn’t comment either, despite multiple requests. Steven Halpert, the Harris County public defender representing the boy, who is legally blind, told the Observer, “If you just met him, you would not have an ounce of fear that this kid is going to shoot up a school, let alone be able to see anybody.”

Advocates for students with disabilities have urged Texas lawmakers to make schools use the kind of threat assessment model that has been promoted by the Secret Service’s National Threat Assessment Center. The approach uses school police, teachers, counselors and other behavioral experts to determine whether a student’s outburst constitutes an actual threat of violence or should be viewed as a “transient” one that needs follow up with mental health services and, if necessary, appropriate discipline.

“If you just met him, you would not have an ounce of fear that this kid is going to shoot up a school, let alone be able to see anybody.”

Whether lawmakers are listening is another matter. Many of the educators, school counselors and other experts who testified at the hearings in front of gun control-averse lawmakers straddled an awkward line. In one hearing last week, they asked for more mental health services for students while trying not to demonize those who need them as threats.

At that same meeting, Lucio lamented that kids don’t get so many hugs at schools anymore. “We can’t do that anymore, but we can embrace them with a simple smile,” he said at one point. Senator Don Huffines, a Republican from Dallas, who was also apparently feeling nostalgic, remembered the good ol’ days when he and his high school buddies brought rifles to school in their trucks and ran fur traps. “What’s so different between now and then?” he said, shaking his head. “What’s changed?”

At Tuesday’s hearing, more educators and parents urged the Legislature to couple “red flag” laws with increases in student counseling services — a two-pronged approach they say would bolster school safety by both helping vulnerable students and leading to better early threat detection. Another man, a very angry open carry advocate, told lawmakers that red flag laws were “a wet dream for local government” and vowed to fight any attempts to take his weapons.

Patrick’s response to the hearing was to all but declare red flag laws dead on arrival in the Texas Senate. If that position holds when the Legislature convenes in January, gun control activists will be left in familiar position: damage control.