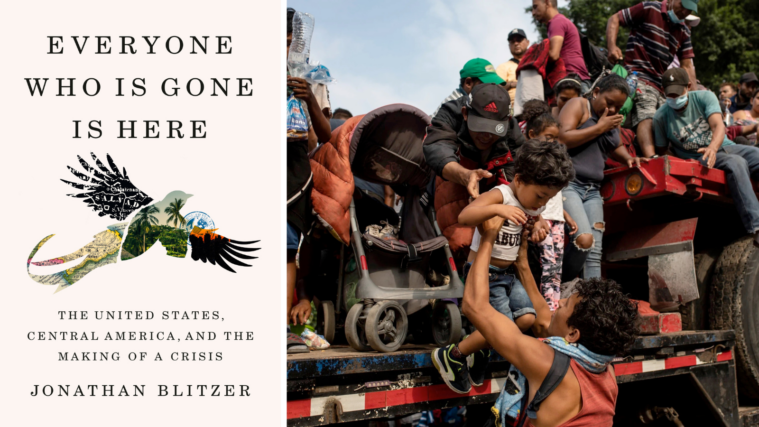

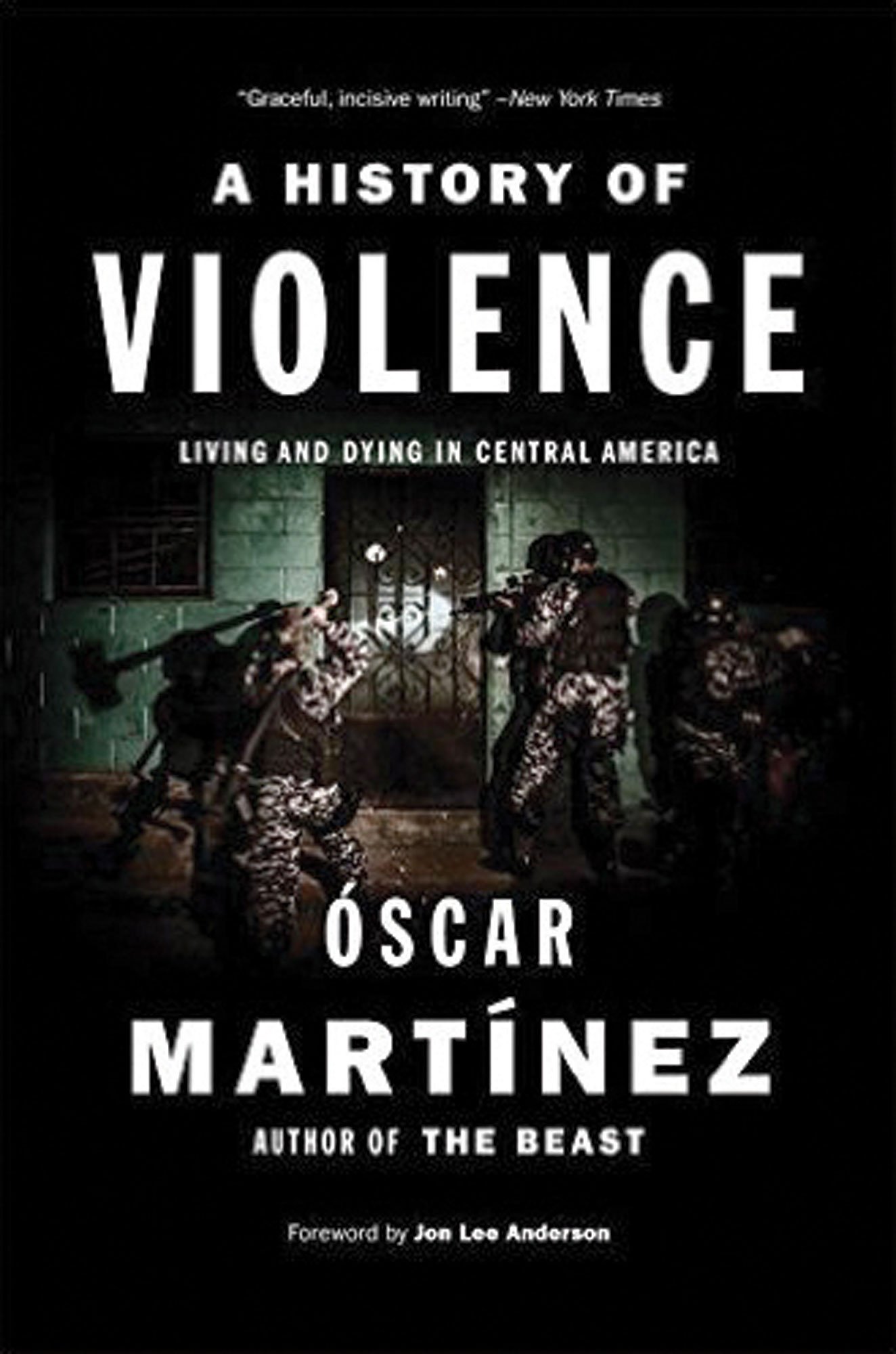

‘A History of Violence,’ a Plea for the Comprehension of Terror

A version of this story ran in the May 2016 issue.

Óscar Martínez

Translation by John B. Washington and Daniela Ugaz

VERSO BOOKS

288 pages; $24.95 (Hardback); $9.99 (Ebook) Verso Books

Reading Salvadoran journalist Óscar Martínez’s nonfiction portrait of violence in Central America, it seems fantastically lucky for all of us that he’s still alive. In the years that he reported A History of Violence: Living and Dying in Central America, Martínez traveled to the most treacherous towns and provinces in Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua, spending days, sometimes weeks, interviewing both victims and aggressors in a conflict nearly as deadly as the civil wars that tore through the region in the 1980s. The reporting is an act of courage; the book is a plea for comprehension of the terror that drives people from Central America to the United States.

Martínez’s preface and the introduction, written by New Yorker writer Jon Lee Anderson, trace the roots of the current violence to the U.S.-Soviet proxy wars that played out in Central America in the 1980s. Just as El Salvador’s civil war was ratcheting up, Martínez writes, U.S. leaders — in a bid to control domestic crime and with the “logic of an ape” — deported 4,000 members of the Mara Salvatruchas (MS) gang from Los Angeles. Once those seeds were planted in Central America, offshoots of MS and Barrio 18 grew into a harrowing web of warring gangs. Today there are as many as 60,000 gang members in El Salvador alone.

The region is in constant combat over narcotics, money, turf, even human beings, who are trafficked for their value as prostitutes or manual labor. “These gangs — La Mara Salvatrucha, Barrio 18, Mirada Lokotes 13 — weren’t born in Guatemala, Honduras or El Salvador,” Martínez writes. “They came from the United States, Southern California to be precise. They began with migrants fleeing a U.S.-sponsored war. And, in fleeing, some of these young men found themselves living in an ecosystem of gangs already established in California. And so they came together to defend themselves, and they established a name, and now this name is what we call our fear.”

Anderson, who covered Central America in the 1980s, points out in his introduction that according to a 2015 Guardian analysis of murder statistics, Honduras is 20 times more violent than the gun-packing United States and 90 times more violent than the United Kingdom — and El Salvador and Guatemala are not far behind. “Today criminal violence has replaced the political violence with levels of bloodshed that come, at times, chillingly close to those of wartime,” Anderson writes. “Outside of the contemporary killing grounds of Syria and Iraq, in fact, few regions are as consistently murderous as is ‘peacetime’ Central America.”

A History of Violence, a collection of 14 separate articles, displays the same powerful writing that distinguished Martínez’s first book, the highly acclaimed The Beast, about Central American migrants who cling to the sides and tops of northbound cargo trains in an often deadly attempt to flee violence, or, in the heartbreaking case of some children, to find mothers and fathers who left them behind in their flight north.

Martínez tells riveting, harrowing stories in his second book, too. El Niño, aka Hollywood Kid — a Salvadoran MS clique member turned informant — spends his days trying to outthink the executioners that he knows are on his trail. Living in a shack in El Salvador, protected by a handful of police, El Niño relies on the questionable safety of a witness protection program. Israel Ticas, the sole working forensics investigator in El Salvador, is trying to dig out bodies, buried under mud and water at the bottom of a well, before the gang members who dumped them there are released for lack of evidence. Grecia, who was sold to Mexico’s Los Zetas cartel while on her way to the United States, is trying to recover her sanity after being forced into prostitution, and after seeing her friend and fellow prostitute burned alive for defying her captors. Like El Niño, Grecia is one of the few people willing to risk testifying against gang members. She, too, is living in the dodgy haven of a witness protection program.

Martínez returns again and again to that point — that the criminal justice system cannot protect the witnesses and informants vital to prosecuting gang members and wresting Central America from their control. After meeting El Niño, Martínez writes that he knows the young man will be killed with the brutality he delivered to others. He dreads the murder because of the people the informant could have helped put in jail if he’d been well protected.

With his talent for dialogue and character, Martínez manages to infuse humor into at least some of the grim stories. Just when the hapless Ticas — obsessed with digging up the bodies dumped in the well — has figured out how to unearth them, and just when the rain and floods have abated enough to do it, El Salvador’s public works department commandeers his dump truck and backhoe. Ticas is foiled again. In Guatemala’s Petén jungle, Martínez meets Venustiano, an indigenous campesino who, along with the rest of his community, has been labeled a narco-trafficker so that an agricultural firm has an excuse to force them off of their land. In the encounter, Venustiano is as amused as Martínez:

“‘So this is where all you narcotraffickers live?’

‘Yep, right here,’ Venustiano says. ‘Follow me. I’ll introduce you to everyone.’

He opens the gate and out peek two men, one tiny and wrinkled, the other leathery and gray. The latter is bathing himself with a bucket of water in the middle of the patio. The wrinkled man yells in the indigenous language of Q’eqchi’. A few older women, as well as about twenty children, appear from several shacks.”

A History of Violence lacks some of the power of The Beast simply because it’s so easy to sympathize with migrants, especially children, who are filled with hope despite the hopelessness of their circumstances. By the end of The Beast, you are totally invested in them. A History of Violence doesn’t allow for the same level of engagement because there are so many characters in the 14 essays, and many of them are horrible people — bullying police, unprincipled coyotes and killers. El Niño whose story reappears at various points throughout the book, tells Martínez that he has killed 54 people, including six women, and as the author points out, the murders are senseless:

“Members of El Niño’s clique once killed an aspiring member because instead of saying he was ‘pedo,’ or high, after smoking marijuana, he said that he was ‘peda,’ the feminine version of the same word. The clique took the mistake as a terrible offense because everything they do is masculine and everything the enemy does is feminine. So they killed him, stabbed him to death on the spot. … There isn’t even criminal logic to many of the murders in this country. There are bones in the bottom of wells for one simple reason: animal violence. Can I kill? Yes. Can I hide the body? Yes. Will it be hard for authorities to find the body? Yes. Will I be looked upon by fellow gang members as courageous? Yes. Thus, I kill. And after a few kills I get used to killing.”

Martínez’s portrait of Central America as killing field is a plea not only for comprehension of immigrants’ race for the border but also for empathy.