Book Review

Road Rage

Driven Wild: How the Fight Against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement

343 pages, $35.

During his relatively brief tenure as chief of the USDA Forest Service, Mike Dombeck launched one of the federal agency’s most controversial proposals. In 1999, the Clinton appointee released what was dubbed the “Roadless Initiative,” a plan that would prohibit the construction of roadways in 60 million acres of the more than 190-million-acre National Forest system. Much of this pristine landscape remains so rough and inaccessible that the possibility of its development is remote, but the initiative was a prophylactic, an added layer of protection for still-wild lands.

President Clinton seemed to understand this strategy when in his October 1999 memorandum directing Dombeck to initiate the requisite administrative proceedings to ensure the land’s roadlessness, he observed: “Too often, we have favored resource extraction over conservation, degrading our forests and the critical natural values they sustain.” As “vital havens for wildlife” and as a “source of clean, fresh water for countless communities,” this forested estate “bestow[s] upon us unique and irreplaceable benefits,” not least of which is that they will remain a “treasured inheritance–enduring remnants of an untrammeled wilderness that once stretched from ocean to ocean.”

Although a mark of Clinton’s belated conversion to a more robust environmental agenda–itself a consequence of blunt, second-term conversations with Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt and others who pressed him to embrace conservation to enhance his meager presidential legacy–the Roadless Initiative nonetheless was a significant act. That’s what more than one million citizens revealed when they spoke at countless public hearings or sent letters or emails indicating their reactions to the proposal; the vast majority of these were positive.

Its significance is evident as well in the enemies it generated. Logging, mining, and wheeled-recreation special-interest groups railed against the initiative and Republicans piled onto the anti-roadless bandwagon during the 2000 campaign. When Bush slipped into the White House in January 2001, Dombeck was shown the door, and by June the new chief, Dale Bosworth, had announced that the Forest Service would “protect and sustain roadless values until they can be appropriately considered through forest planning.” Wilderness is no longer an end unto itself, leaving the proposal in limbo.

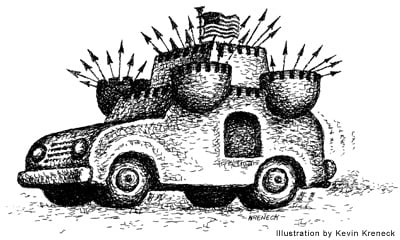

For all its troubled present, the Clinton-Dombeck measure is of considerable historical import. It forced a national debate over the value of wilderness to an urban society; of the unpaved to a shopping-mall culture; of inaccessible space to Soccer Moms and Dads roaming the crabgrass frontier in gas-guzzling SUVs emblazoned with monikers of the hardy (Explorer and Range Rover) and the rugged (Tahoe, Tundra, and Yukon). It only seems contradictory that some of these highly mobile consumers might also care that there be places they cannot not penetrate, except perhaps on foot. But then our cultural relationship to wildness has long been complicated, as reflected in the origins of the organization devoted exclusively to its preservation.

The idea of the Wilderness Society, Paul Sutter notes in his fine (and first) book, was thrashed out in a car. In October 1934, while attending the annual meeting of the American Forestry Association in Knoxville, Bob Marshall, Benton MacKaye, and a clutch of others drove north to inspect a new Civilian Conservation Corps camp. Along the way, they revisited earlier conversations about the need for a national society to protect threatened wilderness, and the discussion became so engaged that they pulled off the road “somewhere near Coal Creek.” There, seated on an embankment, they agreed on a draft of the proposed organization’s preservationist principles.

The core of their argument was that the automobile and the roads on which it ran posed the most severe threat to the vestiges of a once-wild America. Two months earlier, in a memo sent to Interior Secretary Harold Ickes protesting the construction of the Skyline Drive through the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Marshall bore witness to the car’s deleterious impact. “I climbed Clingman’s Dome last Sunday, looking forward to the great joy of undisturbed nature,” but to his consternation Marshall “instead heard the roar of the machines on the newly constructed road just below me and saw the huge scars which this new highway is making on the mountain.” His dismay only increased at hike’s end: “Returning to where a gigantic, artificial parking place had exterminated the wild mountain meadows in New Found Gap, I saw papers and the remains of lunches littered all over. There were about twenty automobiles parked there, from at least a quarter of which radios were blaring forth the latest jazz as a substitute for the symphony of the primitive.” The car had to go.

But without it there would have been no Wilderness Society. As Sutter observes about the spontaneous October 1934 roadside confab, its participants “could not escape the fact that, literally as well as figuratively, the automobile and improved roads had brought them together that day.” So had the New Deal’s energetic conservation agenda. In mobilizing vast federal resources to build dams throughout the Tennessee River valley, carve highways along elevated scenic routes, and construct recreational facilities amid mountain verdure, the Roosevelt Administration provided much-needed work to those most battered in the Great Depression, while opening up, if not defiling, some of the nation’s most pristine terrain. Many of the founding members of the Wilderness Society had worked for, were presently employed by, or were angling for jobs in such governmental agencies as the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Forest and Park Services, or the TVA. In Sutter’s words: “The very conditions that prompted their collective concern had also enabled their concern. That paradox gave wilderness its modern meaning.”

Qualifying his argument’s chronological reach is critical. After all, the intellectual hunger for a natural realm beyond human control stretches back millennia, well before rubber hit the road. Although Sutter makes little effort to flesh out what the pre-modern wilderness values were, beyond inserting a few cameo appearances by Henry David Thoreau, perhaps that’s just as well. We’ve been fed such a steady diet of Sierra Club pablum about the call of the wild, further nourished by the seductive, achingly exquisite photographs that adorn the organization’s annual calendar, that it is hard to question the cultural assumptions behind the message. Nothing speaks to this problem more effectively than the cloying language of an in-house 2002 club advertisement urging members to protect the endangered land and rivers along the route of Lewis and Clark’s famed expedition. Set within a shot of an impossibly beautiful sunset spread against sky and water, through which floats a canoeist at rest, is this faux journal scribbling: “Sometimes lonely is a good thing. Beyond the occasional bird on the wing or rustle of branches, all is stillness here. My mind slows to the rhythm of the oars, and I feel as clear and serene as the lake spread before me.”

By avoiding such tripe, Sutter gives hope that we might be capable of arguing about wilderness (as place and trope) with greater complexity. Certainly his protagonists did, and to be fair, so do many in the contemporary Sierra Club who will recognize themselves in Sutter’s rich biographical portraits of the four men who crucially defined the Wilderness Society’s mission. Their motives and contributions, he finds, were as diverse as any of the ecosystems they sought to defend. Aldo Leopold, whose posthumously published Sand County Almanac (1949) would bring considerable recognition to his vital contributions to environmental thought, had worked for the Forest Service in the early twentieth century. This ecologist, forester, and hunter had convinced the agency to create wilderness areas within select National Forests so that these lands could serve scientific and recreational ends: “good professional research in wilderness ecology is destined to become more and more a matter of perception, and good wilderness sports are destined to converge on the same point.” But to ensure this outcome required an indoor man skilled in the art of pushing paper and people. Enter the society’s executive secretary, Robert Sterling Yard. A journalist-cum-promoter, a man as elitist as he was cranky, Yard had been an effective mouthpiece for the National Park Service until disillusioned by its catering to tourist consumerism. He thus embraced “wilderness advocacy as an alternative to scenic preservation and the recreational developments his promotional efforts had facilitated.” The well-groomed visitor experience the Park Service offered up also offended Benton MacKaye. His background in forestry and regional planning, along with his political radicalism, merged in his conception of the Appalachian Trail; first promulgated in 1921, it was to be “A Retreat from Profit,” a wild footpath that would provide a “refuge from the crassitudes of civilization.” Bob Marshall, yet another socialist forester, shared MacKaye’s faith in the power of wilderness to trump modern capitalism. Born of great wealth, his father was a prominent civil-rights lawyer who taught his son to love the Great Outdoors. Vigorous in play and politics, Marshall was as stout a defender of nature as a “preserve of liberty” as he was an “unabashed critic of the environmental and social results of economic liberalism.”

Through his deft analysis of this motley crew’s aspirations and contradictions, Sutter has reminded us just how messy environmental politics has been. By recovering an important set of inter-war arguments about the manifold threats the motoring masses posed to wilderness, Driven Wild has also revealed the deep intellectual roots from which grew the Wilderness Act (1964); its passage remains the greatest achievement of the society Leopold, Yard, MacKaye, and Marshall brought into being. But the book is of contemporary relevance, too, shrewdly illuminating the context of our unending struggle to corral the car.

Contributing writer Char Miller is author of Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism (Island Press), which won the 2002 Independent Publishers Biography Award.