Afterword

Trinity Site: America's First Ground Zero

Entering White Sands Missile Range is like driving into another reality. Barbed wire glints in the sun, razors gleaming; spattered on the distant mesa, odd, dome-shaped structures break the horizon. Signs read, Explosives Turn Here; No Photographs!; Visitors MUST Stay On Road At All Times. At the Stallion Range gate, the northern-most entrance onto the missile range, soldiers are handing out brochures and checking trunks of the cars at the front of the line. The line is long and slow- moving; people are edgy, security is tight. At eight in the morning, the New Mexico landscape is saturated with light, golden and ethereal. Beyond the barbed wire, nearly transparent yucca flowers billow in the breeze, purple prickly pears swell on cactus pads, ocotillo buds close like small red fists.

Aside from being one of the largest, most elaborate, sophisticated army bases in the world, White Sands Missile Range is also one of the most unassuming. For the most part, all there is to see is desert–3,200 square miles of it. It’s hard to believe that within the bounds of this barbed-wire fence almost every missile and rocket, bomb, bomblet, and space laser in the U.S. arsenal has been tested: the V-2, the F-117 “Stealth Fighter,” the Delta Clipper, the Pershing, the Pershing II, The Patriot. The High Endoatmospheric Defense Interceptor, the Mid-Infrared Advanced Chemical Laser. Cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, anti-ballistic missiles. The list goes on and on. This stretch of remote, seemingly barren desert is like a great disguise, concealing a hub of top-secret missile and space activity.

In the beginning, remoteness was the trump card. In 1945, Robert Oppenheimer, the lead scientist of the Manhattan Project, selected White Sands as the site for the construction and testing of the world’s first atomic bomb from a list of eight possible sites in California, Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado. The area known as Jornada del Muerto (aptly translated, journey to death) was chosen for its seclusion and relative proximity to Los Alamos National Laboratories, where the bomb was to be engineered and designed. The test occurred on July 16, 1945, and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki followed within weeks. Almost 60 years later, Trinity Site’s Ground Zero is one of America’s creepiest National Historic Landmarks, open to the public only two mornings a year, the first Saturday of April and October.

Growing up in Las Cruces, New Mexico, not 20 miles from the southern entrance to White Sands, I was instilled with a certain pride in the Missile Range. In Las Cruces (often dubbed Bomb Town, USA), it provides more than 4,000 jobs–the best the area has to offer. In combination with the adjacent NASA facility, missile and space technology is the mainstay of the local economy. In Albuquerque it’s the same story; Kirtland Air Force Base and Sandia National Laboratories are the leading employers in the state. When you grow up among people whose lives depend on the weapons testing industry, it’s hard to root against the missile range; I grew up believing it was the home team. The people who worked there are good, hardworking folks–my father’s best friend, several cousins. Trinity Site, which sits in the northern section of the missile range, was the crown jewel, a point of focus and pride. This ideal, of course, conflicts with a less comfortable set of facts: the lives lost to the atomic bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the backhanded way the U.S. government annexed the land for the site from New Mexico ranchers and farmers–not to mention the tragic effects on humans and the environment caused by nuclear weapons manufacture and testing in this country, the turmoil created in a world where weapons of mass destruction are a constant threat.

When I reach the front of the line, a soldier hands me a sheet of “entry rules,” along with an informational brochure. The procedure has obviously changed since my last visit. While some of the rules make sense (pets are to be kept on their leashes; motorcyclists must wear helmets), rule number two is distressing: “Demonstrations, picketing, sit-ins, protest marches, political speeches and similar activities are prohibited.”

Protests, ranging from poetry readings and prayer services to anti-war rallies and peace circles, have been a fixture at the Trinity Site for years. It has always seemed fitting that the missile range should encourage such activity, that the circle of scarred earth should serve as a monument to free speech. Indeed, one might argue that the atomic bomb was employed to protect these freedoms. The Trinity Site opening should be a day of contemplation, of mourning, and, most importantly, a day when the site is open to the entire public, including poets and protestors. But now that right to free speech has been denied.

Something else had changed since my last visit. The first time I visited Trinity Site, the place was nothing more than a simple circle of fence. One sign read, “radioactive material.” Another warned against touching the ground, eating, drinking or applying make-up at Ground Zero. It was creepy, but allowed for contemplation. Today armed soldiers direct traffic in a huge, newly paved parking area located 20 miles from the entrance gate. Tourists spill out of their cars, readying their cameras and collecting their children. RVs line one full side of the parking lot, and in an adjacent lot hot-dog and soda stands are set-up. There’s a booth where vendors sell T-shirts and ball caps on which is printed a tacky orange-red graphic of the mushroom cloud exploding. “Trinity Site,” they read, “Home of the First Atomic Bomb.” Farther out, by the endless row of port-a-potties, a Boy Scout Troop assembles. When asked why they came, the troop leader shrugs, and tells me, “Boy Scouts like things that blow up.”

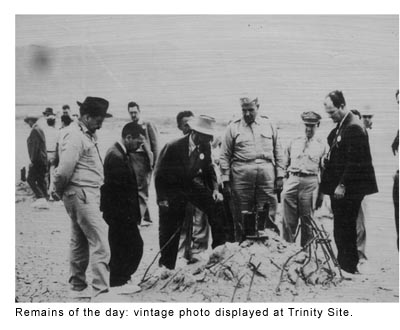

At Ground Zero, the spot where the bomb was detonated, an obelisk stands, declaring the site a National Monument. Photos of bomb construction–shots of scientists and the young, bright-eyed soldiers who acted as their aides–are prominently displayed along a section of the fence. A hundred-foot tower, on top of which the bomb was detonated, disintegrated in the blast; all that remains is one of its footings. People gather around the snarl of steel, photograph it, videotape it, pose with it. A small section of earth at Ground Zero is covered and preserved, green and glassy. That’s Trinitite, the substance the desert sand became the moment the bomb was exploded. Although most of the Trinitite was removed from Ground Zero in the seventies, small chunks of the stuff can still be found, dazzling in the silt, luminous and strange.

At the center of Ground Zero sits a replica of the Fat Man bomb–the bomb dropped on Hiroshima–alone on a flat- bed trailer. As a joke, someone has written the words EXPLODE ME in the desert-red dust on the tail. As the morning burns on, a few children begin to cry, bored and miserable in the desert heat. The crowd thins out and is replenished while a docent from the National Atomic Museum gives a long lecture on bomb construction, telling jokes, and showing off a Geiger counter, his words warbling out of two small speakers. As I chat with the visitors, most say they’ve come to the Trinity opening out of an interest in history, an interest in science, a deep sense of patriotism or simple curiosity.

On July 16, 1945, at 5:29 A.M., Mountain War Time, the New Mexican sky lit up and nothing was the same again.

When I was a little girl, my grandmother often told me about the explosion, which she witnessed from more than 150 miles away. “I could see the neighbor’s house,” she said of the moment the pre-dawn sky was lit up, spilling an eerie, greenish light into the front yard. It was silent, no sound, only light. A few minutes later, the sun–the actual sun–rose. In the days that followed, news agencies reported that an ammunitions dump had accidentally exploded. But many years later my grandmother would confide that all along she knew it was something else, something bigger, something awful. So did most everyone in New Mexico. And they were right: The day after Hiroshima was bombed, the government publicly announced the Trinity Test.

More than 300,000 lives were taken by the bomb tested in our backyard. Several hundred thousand U.S. servicemen and women were exposed to dangerously high levels of radiation. Today, the design, manufacture and testing within America’s nuclear weapons complex has left a countless–and far too often voiceless–many with radiation-related illnesses, including but not limited to beryllium poisoning, plutonium poisoning, leukemia, and multiplemyeloma, as well as cancers of the breast, bladder, colon, liver, lung, esophagus, stomach, thyroid and skin.

Trinity Site remains an ironic metaphor, one that is particularly American with its confused and conflicting realities; a spot in the middle of nowhere where the entire world changed forever. Its scarred earth should be considered sacred ground–or cursed ground, whatever best speaks to the magnitude of its meaning. Perhaps, most fittingly, America’s first Ground Zero should be a place where the public is free to praise or protest, sing or be silent, pray or spit. That’s not the place I saw last April. I saw a place that was losing its meaning and turning into just another tourist attraction off I-25. No more protests, just hot dogs and souvenirs. Entry rules and RVs. One road in, one road out.

Carrie Fountain is a student at the Michener Center for Writers at UT-Austin.