Dateline Texas

Sweet Union: 25 Miles to Lufkin, 70 Years Behind the Times

The community of Sweet Union in Deep East Texas is not on highway maps. It’s easy to drive past it and see only the soft undulation of the land and the cattle grazing in the meadows, missing the dilapidated shacks set back from the road. The only way a visitor knows they have arrived is a sign on Farm Road 1247 that identifies the Sweet Union Cemetery. It’s an apt marker for a place where death and decay seem to have gained the upper hand.

Across the farm road from the cemetery is the Sweet Union Baptist Church founded in the 1800s. Next door is an old wood-frame school house that served its last child almost 40 years ago. Locals say the school was one of the more than 500 Julius Rosenwald built in Texas. The son of a German-Jewish immigrant, Rosenwald made his fortune in the early 1900s as president of Sears, Roebuck and Company. He then used his wealth between 1913 and 1932 to help rural black communities in the South construct more than 5,000 schools for themselves. It’s the type of philanthropy that might hold the key to Sweet Union’s resurrection, even though ironically, Rosenwald’s school may unintentionally have contributed to the community’s demise. It’s a familiar story for much of the South: As education levels for blacks improved, employment opportunities did not keep pace. The end of segregation only fueled what had become a massive migration to the cities, further impoverishing the countryside.

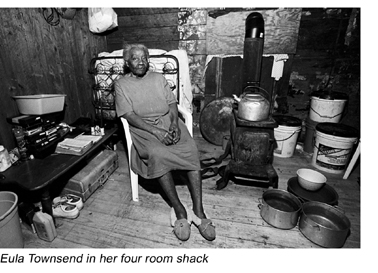

Today the average age in Sweet Union is 62 and the poverty in which many live is reminiscent of the destitution found during the Great Depression. Down the road from the church, 81-year-old Eula Townsend resides in a decrepit four-room shack. Out front is parked a Buick Electra that long ago ceased to run. Cobwebs cover its tires. Townsend navigates the sagging wooden steps that lead up to the house with difficulty, her speech and mobility hampered by back-to-back strokes in November. She shuffles across the thin wooden floor and settles into a threadbare armchair.

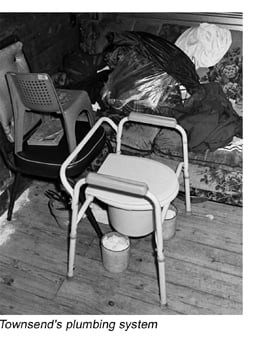

In the 21st century, in one of the wealthiest nations in the world, her house has no indoor plumbing, no bathroom, no running water. Although there is a waterline available, she cannot afford to connect to it. Instead she and her daughter, who share the home, gather water from a well behind the house. A fire that serves as garbage disposal burns 10 feet away from the well, which consists of a concrete cylinder sunk into the earth, covered by a large sheet of plywood. The water is at least 15 feet down. The Townsends draw the water up in pots which sit open on the floor inside. Nearby is a white portable toilet, like a child’s practice potty, with a compartment underneath that can hold several days of waste. A solitary window-unit air conditioner in the front room is all that wards off the oppressive summer heat. Against the wall, a couch hides a hole large enough to swallow a teenager.

We have come visiting Townsend with Revous Taylor, who is a real estate developer in Dallas. The 56-year-old Taylor grew up in Sweet Union and traces his family back to the freed slaves who founded the community after the Civil War. In the Sweet Union of his childhood, the farm road through town was dotted with homes and people strode the red clay roads. Neighbors took care of each other. “I remember when my father would slaughter the hogs, the first couple would go to the community,” he recalls. “We would help each other out. When someone’s house burnt down, everybody would help rebuild it.”

Taylor is part of a handful of professionals who left the area long ago to build careers in the big cities, but are now reconnecting to Sweet Union in an effort to halt the downward spiral. They call themselves the Sweet Union Development Corporation. One of the people they have set out to help is Townsend. Taylor estimates that of the 50 or so houses left in Sweet Union, about 40 percent don’t have indoor plumbing. When at their behest, the U.S. Agricultural Department tested the wells, they discovered that many are infected with parasites.

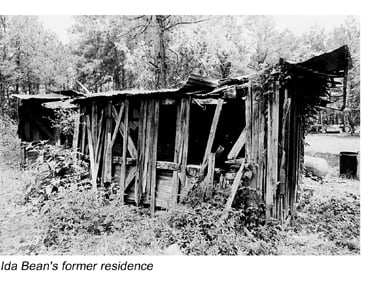

About a mile from Townsend’s house down an empty road is the skeleton of an old wooden railroad car. Ida Bean bore five of her twelve children in the car, which she moved into after marrying her husband Dennis in the early 1950s. The boxcar had opened up when its previous occupant, Dennis Bean’s grandfather, died. In those days, the residents of Sweet Union survived by keeping gardens, cutting firewood, and laboring in the sawmill or the smoke houses. Sometimes they would travel to the Panhandle to pick cotton. “Back [then] people had a lot of kids just to help them on the farm,” recalls Taylor.

Today Ida Bean lives in a proper home nearby. Dennis Bean died in 1998 and the house is now in need of serious repair. The development corporation is trying to fix the leaky roof, restore the buckling floors, and insulate the walls. As part of that effort, the group recently held a catfish fry and yard sale in the old school house to raise money and awareness for their efforts. For Wanda Thomas, who lives in Houston, it’s one more step in a process that she realizes will take time. Thomas is from Maryland and works for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs as a business development coordinator. Her husband Charles comes from Sweet Union and is president of the development corporation’s board. She explains that when they first started to assess needs and get people involved about five years ago, to her surprise residents were wary. They suspected an ulterior motive. “I really thought people were going to be beating down the door, not siccing their dogs on us,” she recalls.

The group sent letters all over the country to anybody who had a connection to the community, but received few responses. Many were skeptical that anything could be done. Some who belonged to other churches were reluctant to meet in the Baptist-owned property that had become the group’s headquarters. So they decided to build a community center. Businesses in neighboring towns as well as both white and black churches have contributed. A local landowner has agreed to donate six acres of land on which to build the center.

In one respect the people of Sweet Union are lucky. They have an abundance of land. According to residents, Rube Sessions, the wealthiest man in the neighboring white community of Wells, helped those who worked in his sawmill and the stores he owned to buy their own property in the early part of the last century.

“Practically every family bought their own homes and farms, but if they don’t try to preserve it, it will all be gone,” says 74-year-old Princella Hughes.

It’s not an idle fear. Land traders scour the South looking for poor communities like Sweet Union where people have died without leaving wills. The properties they leave behind are held in common by the surviving relatives. If just one of them sells an interest in the land, the land trader can take it to a judge and demand that the land be auctioned. It is just one of many mercenary strategies that helped drop black land ownership from 15 million acres in 1910 to 1.1 million acres today, according to the Department of Agriculture.

The long-term goal for the development corporation is to turn Sweet Union into a retirement center for the elderly from all over the area, says Wanda Thomas. She stands in front of the church and looks at the graveyard. “There is a lot of history here,” she says. “It’s such a shame the way it has reverted back; it’s like it never existed.”