From the House of the Grave: The Two Fridas

The Incantation of Frida K.

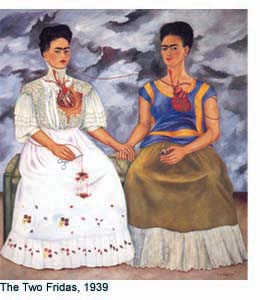

The Two Fridas, perhaps the most famous and beloved painting by Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, features two images of the artist seated side by side, hands clasped, one in Victorian dress and the other in Tehuana costume. Drawn in precise detail, their two hearts are worn like accessories on their clothing and a blood vessel ribbons between them.The duality of Kahlo’s intertwined self-portraits is analagous with the two representations of the artist’s life found in both Meaghan Delahunt’s luminous debut novel and the dazzling The Incantation of Frida K. by veteran writer Kate Braverman. Delahunt’s In the Casa Azul unfolds in geographical locations as diverse as Moscow, Mexico City, and Barcelona, and meticulously recreates the historical events that led up to Leon Trotsky’s assassination in 1940, just minutes from the home of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, where Trotsky had been living in exile. Braverman’s scope is more defined; her razor-sharp prose traces Kahlo’s inner thoughts in the Demerol-mist of her final days at the Casa Azul, the house painted “the color of a child’s first chalked sky.”

Although In the Casa Azul opens with Kahlo’s 1954 death, the artist is primarily a touchstone for the memories of other characters.

Trotsky, the best-drawn character in the cast of many, describes Frida as “the most self-realized woman of her time,” but the narrative quickly acquiesces to stereotypical descriptions: the allure of her “irregularities” as “the crack in a Grecian urn draws attention to its beauty. As the flaw in the glass draws attention to its clarity.” More interesting is the spark between Kahlo and Trotsky: Both objects of others’ desire and obsession, they were magnets for politics and people, and both understood the pain of creating art and ideas in exile–Frida from her body and Leon from his country. They were, in these and other ways, a perfect match. Their love affair caused Trotsky’s break with Diego Rivera in 1939, two years after Trotsky and his long-suffering wife Natalia found refuge at the Casa Azul–”that house: the cradle and the grave.”

The first artistic strategy Delahunt uses to explore “the dialectic of love and art and revolution” is largely successful. Weaving together multiple narrative voices, none receiving more than two to six pages at a time, is a clever, if risky, way to cover large periods of time. These leaps in time and geographical location are so well woven that the reader, like many of the characters, feels moved “from participant to witness,” and the book, although dominated by flashbacks, maintains its narrative urgency.

While some of the characters become less compelling as the novel progresses, others, like Stalin and Trotsky, bloom into fascinating individuals. Impressive is the author’s ability to build and maintain sympathy for each of her characters, from the murderous Stalin to the self-righteous Trotsky and even the egotistical Diego Rivera, who is seen grieving for his wife Frida in the novel’s opening scene.

Delahunt’s other narrative decision has mixed results. She locates the heart, or morality, of the story in the characters who did not make history, but were forced to reckon with its consequences; namely, bodyguards, farmers, industry workers, and other members of the working class. Although anchoring the larger moral lessons in these narratives allows Delahunt inroads into the daunting task of fictionalizing imposing historical figures, the blocks of almost pure moral insight can feel a bit forced and self-conscious, with divisions between people too neatly drawn.

The “outsider” strategy functions well, however, in two places. First, “The Other Moscow” chapters follow the life of Mikhail, a devoted Stalinist charged with the “treacherous work” of building the Moscow metro system while surviving on mushrooms from window gardens, and rabbits his mother raises in their “loud and damp” flat. Meanwhile, the wasteful Stalin abuses his wife and closest colleagues, concerned only with increasing his power and influence.

In another scene, while marching to Odessa during the Civil War, Trotsky’s father asks, “Can someone tell me…how we came to this?” The answer of course, is his son, “travelling by armoured train” to commandeer supporters, offering “rewards and punishments in delicate balance” while his father’s friends are “scratching themselves to the grave” with typhus. It is a testament to Delahunt’s skill as a storyteller that the reader is horrified at this terrible irony and still feels sympathy for Trotsky.

Another misstep in the book is the assertion that “Judas the apostate” is “the axis on which the whole story turns.” Treated as the metaphorical glue that holds the narratives together, some characters directly refer to Judas several times; with betrayal already an obvious theme, it feels heavy-handed. However, in a book that delicately balances so many characters with its beautiful language, the reader can forgive these overly tidy metaphors.

The answer to Delahunt’s question, “How does exile alter the balance of a person?” finds an answer in Braverman’s brutally self-aware Kahlo: it destroys it. The Incantation of Frida K. does not mince words–why should it? Stripped of physical health after a trolley accident that destroyed half of her spine, Kahlo is so starved for affection that she creates an imaginary child simply to have someone to love. Her marriage to Diego Rivera offers no solace–it is merely “a form of war.”

The stunning portrayal of Diego and Frida’s relationship forms the emotional heart of the book. This “big man, enormous in his flesh,” demeans Frida at every opportunity: ” ‘You are too distorted to be a woman. You mock proportion. You are disgusting,’ Diego was studying my back, my legs. ‘You are the opposite of a miracle’.” Braverman never relents in her chilling portrait of him and the reader is convinced by the opinions of this bewitching first person narrator:

Frida and Diego, the new ruins. You can’t miss them. She’s a bolted-together cripple who talks like a stevedore. He’s the size of a boat. It’s always cocktail hour at their place. The house is a brothel. Their life is theater. There’s a line. Get a ticket.

A self-described “trained monkey,” Frida accuses Diego of trotting her out in Tehuana costume at public events and at her own exhibitions, where she was often too sick to stand: “I was a portable decoration, like a piñata.” Humiliated and objectified by this treatment, she was “already a woman you must speak of in whispers.”

Much has been made, particularly by Delahunt, of Frida’s dedication to the Communist movement and identification with the working class: “She knows what it is to slide up against the gravity of life, her hands full of promise, to slide back down again, with nothing. Her spine broken, her leg withered, in her hand a fistful of brushes.” Braverman’s Frida refuses this portrayal, likening her political involvement to an element of the show: “They thought my costume asserted loyalty to my culture, and solidarity with workers, the masses. They did not recognize the obvious theater of me.”

Braverman’s Kahlo wants to resist all categories, particularly with reference to her art, which she insists is not surrealist:

I am painting reality. This is not a dream… .The woman impaled with sixty-seven nails is not a hallucination…the woman with her heart ripped out…is not an invention of the imagination, an exaggeration, or a product of fever. I know this woman.

Arguably, the reader does not know this woman, being more familiar with the popularized image of Frida Kahlo that has appeared on magnets, postcards, and lapel pins in recent years–a marketing campaign that has elevated her to iconic status. Tweaking this irony is perhaps the greatest accomplishment of Braverman’s book, which gives us a very different Frida: a Frida of barbed words and bitter thoughts; a Frida who keeps a “hopeless chest”; a Frida afflicted by her back, “with its war zone of barbed wire perimeter and ditches”; a Frida who paints to avoid total oblivion. This woman’s image is not the one captured on postage stamps.

Frida’s 1939 response to selling a canvas to the Louvre–”I had expected this only after my literal death. That is the way with women artists. When she is dead, she cannot harm you”–is incredibly ironic in light of the fact that In the Casa Azul and The Incantation of Frida K. are both being promoted in connection with a feature film about Kahlo’s life starring Selma Hayek.

Just like the famous painting, there is a unity in the two different recreations of the woman and the artist Frida Kahlo. Delahunt’s interwoven narratives read like a sensuous, dangerous dream, while reading Braverman’s prose can be likened to touching an electrified fence. Neither experience–and neither Frida–is easily forgotten.

Observer intern Emily Rapp is a student at the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas at Austin.