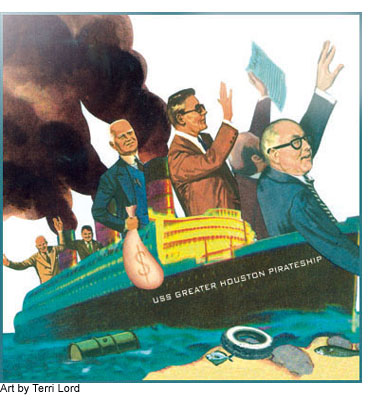

Harris County Hijacking

How Big Business Pirated Enviro Funds to Fund Its Own Non-Compliance

It’s more complicated than this, and we’ll get to that, but basically what just happened, while hardly anyone was watching, went down thusly: A big-business front group in Houston hijacked a pile of environmental mitigation money to fund its own kicking, screaming, and continuing fight against Texas’ clean air plan, and did so, if you can believe this, with the full support and blessing of the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission, the state’s environmental agency, which was itself recently sued to a standstill over clean air regs by the very same industrial lobby.

The business front group is called the Greater Houston Partnership, and the TNRCC, which has devolved into something of a laughingstock under its current initials, will soon change its name to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. As for the machinations behind this particular sleight of hand, you could call that out and out piracy. Or, if you’re in a bleak mood, you could just call it business as usual.

The Coastal Impact Assistance Program crossed news desks last year with the deafening silence of yet another unmemorizable acronym dripped into a sea of same, but to the few enviro organizations and county governments with a stake in its provisions, the CIAP was a godsend, a windfall, and an opportunity. Authorized by Congress in 2001, CIAP legislation appropriated $150 million dollars to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for distribution to seven coastal states for the purpose of “protecting and restoring coastal resources and mitigating the impacts of outer continental shelf [oil and gas] leasing and development.”

Texas’ haul of the one-time appropriation came to about $26 million, the largest of any state. Land Commissioner and Lieutenant Governor-hopeful David Dewhurst was the biggest beneficiary–one third of the money was distributed through his General Land Office (GLO), and another third through the Coastal Coordination Council, of which Dewhurst is the chairman. Both agencies ostensibly used a graded grant process to disburse their portion of the funds. The remainder of the award was allocated directly to eligible coastal counties, which assigned moneys to projects as they saw fit.

When the Land Office announced its grant recipients in December, dozens of worthy environmental projects made the list, including beach renourishment in Galveston, public land acquisition of the last stand of coastal hardwoods on the Texas coast, and wetland restoration up and down the coast.

But to the few people with any reason to look closely at the list, one grantee’s endeavor stood out like a sore thumb: The state, under Dewhurst’s watch, had funneled $2,250,000–its largest single grant and 15 percent of its total coastal impact funds–to the Greater Houston Partnership, for something the Partnership was calling an “Ozone Science and Modeling Research Project.” Meanwhile, Harris County, under the leadership of County Judge Robert Eckels, allocated 100 percent of its share of the funds, or $1,855,770, to the same project.

To fully understand what’s so squirrelly about this, a bit of background is required.

The Greater Houston Partnership is basically a high-octane Chamber of Commerce. Shell Oil CEO Steven Miller chairs the board, which represents business honchos from Conoco, ExxonMobil, Reliant Energy, Halliburton, Lyondell Chemical, Dynegy, and El Paso Energy, alongside political establishmentarians George Bush the elder, various Mischers and Mosbachers, and the law firm of Baker & Botts. Enron fall-guy Ken Lay is also on the board, but one wonders how active he is these days.

The Partnership’s stance on clean air is conflicted. A subset of the Greater Houston Partnership–the Business Coalition for Clean Air–last year spent $1.1 million on “Clean Air: It’s Everybody’s Business,” an ad campaign featuring frolicking children against a backdrop of presumably ozone-free skies. Yet that same group, in January 2001, filed suit against the TNRCC over what it claimed was the faulty science employed in crafting the State Implementation Plan, Texas’ latest set of clean air regulations.

The Partnership’s position is that the complex computer modeling employed by the agency is not accurate enough to justify the stringent reductions that the TNRCC–which is charged with bringing Houston into compliance with the federal Clean Air Act by 2007–imposed on industrial polluters in 2000. Waving, like a club, a Partnership-commissioned study that claimed compliance would cost area industries over $13 billion, the Partnership’s lawyers forced the TNRCC to admit in court what everyone on both sides of the clean air debate readily admits: The science is indeed imperfect, although exactly who is to blame for this (more on that later) is a matter of some controversy. A judge stayed the case in May 2001, following TNRCC’s agreement to do further studies. In the meantime, the existing regulations continue to apply.

Here’s the kicker: The Partnership’s “Ozone Science and Modeling Research Project” is the further study. The grant application defines an $8 million project, of which just over $4 million comes from the coastal impact funds. The remaining $4 million, line-itemed on the grant as originating from “other sources,” actually comes from a 2001 legislative appropriation to TNRCC to do its own studies. Who exactly will control TNRCC’s $4 million contribution to the project is fairly muddy water. The TNRCC claims it does, but the Partnership lobbied hard to place the money in the agency budget, and claims, in a summary report of its legislative agenda available on the group’s website, that TNRCC “will direct these funds to the consortium” that the Partnership has set up to oversee its research. (A Partnership spokesperson, questioned about that wording, called the phrasing a “misstatement” and claimed that TNRCC remained an autonomous partner.)

But if there’s any question as to the Partnership’s scientific goals–beyond the predictable posturing about the need for “better science”–that is answered on the grant application as well. After a cursory attempt at linking the project to coastal impacts (“Air quality impacts the water, food and shelter resources needed for the survival of the birds…”), the Partnership gets down to business: “It is anticipated that the more accurate controls developed using a recalibrated model for the [Houston-Galveston Area] will reduce the economic burden to the region by $9.15 billion.”

Check that specificity. Two proposed years of intense study and research in the highly volatile and ever-developing prediction of ozone formation, in a region blessed with emissions sources in the millions, and the Partnership can already estimate, to that last point-one-five, how much their studies will save them. Next time you see a seventh grader, ask them to explain to you just what’s wrong with that science.

John Wilson is the executive director of GHASP, the Galveston-Houston Association for Smog Prevention, and he laughs right away when asked about CIAP funding. “This idea that these coastal moneys, which are supposed to go for coastal impacts, are going to start funding air quality research is a bizarre thing. It’s not something we would have advocated if we had known it was happening. We would have been there and opposed it. And not just because the Partnership is involved, but just simply because we don’t want solid waste funds raiding air quality funds, so why would we want air quality funds raiding wetlands restoration funds? I mean, we’ve got enough problems fighting over money with the Legislature as it is. Watching for creative nabs across media just makes it worse.”

But almost no one was watching Dewhurst’s General Land Office as it went through the process of deciding which projects to fund, and even now, the GLO’s press liaison is less than forthcoming with details of what, if any, process guided its selections. The dominant assumption within the few camps that even know what CIAP stands for is that the jury was rigged from the inside, and from the start.

John Hall, the one-time TNRCC director who now directs the Partnership’s new research project, explains it this way: “The Governor and the Land Commissioner recognize the importance of better understanding ozone formation in the Houston-Galveston region,” and “redirected some federal grant dollars” the Partnership’s way. Anne Culver, the Partnership’s Senior Vice President for Government Relations, says her lobby “coordinated a petition in Harris County and petition[ed] the governor for utilization of all or part of their CIAP funds.”

“This source of funding,” Culver says, “is like hey, wow, it’s one-time-only money, our project fits the criteria, let’s go after some of this money.”

But does the project fit the criteria? Some of the project money came directly from the GLO, and more was apparently requisitioned from the Coastal Coordination Council’s pot. Despite repeated requests, GLO public information officer John Kerr declined to make any of his office’s staff available for interviews on the subject. But San Patricio County farmer John Barrett, one of four citizen members who sits on the executive committee of the Coastal Coordination Council, and who helped judge and rank the Council’s coastal impact grant applicants, paints a pretty good picture of an agency bending over backwards to accommodate the Partnership’s agenda.

“I think, to be as frank as possible, there was a lot of interest in that project in Austin, and it was a project that I believe that a lot of people supported,” Barrett says. “I think there was a fairly clear understanding that that particular project, it’s something that the leadership from Harris County really wanted to have happen.” That was why, according to Barrett, the Council expedited the Partnership’s grant request.

But some obvious stakeholders, according to Barrett, were cut out of the loop altogether. The TNRCC is part of the Coastal Coordination Council, as is Texas Parks and Wildlife, the Texas Water Development Board, and the State Soil and Water Conservation Board. “The Land Office had their own review team for their projects. None of the other Council member agencies or the public members of the council, none of us were involved in the Land Office’s ranking process.” Andy Jones, director of The Conservation Fund in Austin, also remembers the muffled uproar caused by Dewhurst’s unilateralism on the Partnership grant: “They went through a process in-house. None of the CCC member agencies were participants in the first cut…. And they got enough heat from the other agencies that are members of the CCC that they had to include those people in the rest of the rounds.”

But by that time, the Partnership’s proposal was golden, and Houston’s industrial business community had purchased–with hijacked funds–a seat at the table around which Houston’s Clean Air plan will be hammered and tweaked and twiddled into just what shape no one yet can say.

Anne Culver, speaking for the Partnership, will tell you that this is all perfectly aboveboard and virtuous, as will Harris County Judge Robert Eckels and TNRCC spokesperson Patrick Crimmons. The front is unified and the case that they make goes a little something like this:

Yes, Culver unabashedly admits, up until maybe five years ago, the business community that the Partnership represents “was probably a little more interested in trying to figure out a way to completely avoid the situation than step up to the plate and go ‘You know what? The air’s dirty’.” (And in fact one of the Partnership’s precursor organizations, the Chamber of Commerce, in the 1970s funded a Houston Area Oxidants Study in an attempt to discredit Environmental Protection Agency research on the negative health effects of high levels of ozone).

But according to Culver, ever since the city’s air quality was used as a punching bag in the 2000 presidential elections, Houston’s business community has seen the light.

“We’ve got to get it cleaned up. Now. We agree with that. It’s a black eye. It’s going to keep people from wanting to move their businesses here, it’s going to keep smart young people from wanting to move here for good jobs when they graduate from college…. I think the turning point came about three or four years ago when this whole community, with all the work we’ve done on rebuilding the inner core of the city, all the emphasis on diversifying our economy away from energy, all those things we have to do to be sure that we’re very competitive for corporate relocations… on that list is quality of life and image, and a huge black eye for us is this non-attainment standard. And all this stuff about Houston surpassing L.A. as the smoggiest city… We’d like to be #1 on lots of lists, but not the list of dirtiest cities.”

Thus far, the Partnership’s efforts towards clean air have included little more than an advertising campaign, extensive lobbying efforts aimed at securing tax breaks and exemptions for its friends in the petrochemical and construction industries, and the formation of an offshoot organization founded specifically for the purpose of litigating against clean air regulations. Their record notwithstanding, the Partnership hangs its hat on the paramount importance of smart science. “It’s an economic problem to address this in the wrong way,” Culver explains. “It will be false economy and flushing dollars down the drain if we don’t so it smart.”

According to the Partnership, and, somewhat less emphatically, to TNRCC, funneling coastal impact money and regulatory research funds into one giant pool of study money is a win-win situation for everyone involved: It will hopefully produce better ozone modeling on which to base revised regulations in time for the mid-course review of the state’s clean air implementation plan in 2004. The way they see it, TNRCC had identified a pile of needed research that it just didn’t have the money to carry out, so the Partnership stepped in with a helping hand, bringing money to the table from whatever sources it could cobble, because we are, after all, all in this together.

Houston’s usual-suspect environmental lawyer and chairman of the Galveston Bay Conservation and Preservation Association, Jim Blackburn, has a hard time seeing it that way. “I don’t question the need for better computer modeling. I question whether it ought to have been funded by coastal impact money, but more importantly, I question whether it should have gone to the Houston Partnership,” he says. “And I want to be real sure that there’s no overlap between the Houston Partnership’s support of this challenge to the air quality plans [the Business Coalition for Clean Air’s litigation against TNRCC] on the one hand and on the other hand the work that’s going to be done with the proceeds of this coastal impact funding. Because I think that would be highly improper.”

The Partnership has gone to great lengths to give the appearance that it is engaged in purely objective, fully credentialed, and thoroughly peer-reviewed science, sans agenda (excepting, of course, its stated goal of a $9.15-billion reduction of its own economic burden). In February, the Partnership formed the Texas Environmental Research Consortium (TERC) to oversee its modeling research. John Hall, the business-friendly former TNRCC director, will head the group, which is housed in the offices of the Houston Advanced Research Center in the Woodlands. A board of directors has been partially named, including Harris County Judge Robert Eckels, Houston Mayor Lee Brown, Colin County Judge Ron Harris, and Environmental Defense’s Jim Marston. (Marston is also on the board of the Texas Democracy Foundation, publisher of The Texas Observer).

The Consortium’s work has just begun–the board is not

et filled, funding for three initial

esearch projects has only recently been approved, and the consortium’s “strategic research plan” isn’t expected to be complete for another month or so. At this early stage, even skeptics like GHASP’s John Wilson concede that the Partnership has put an impressive infrastructure in place to oversee the study money, necessitated by the strict requirements tied to federal funding.

Still, there are suggestive connections, and not everyone believes that the Partnership’s place at the table has been set without self-interest. For one thing, no representative from the state, much less the TNRCC, has yet been named to the Consortium’s board, though the Partnership has its representative firmly in place in the person of former Partnership chairman Bruce LaBoon. Director Hall says he fully anticipates that the Consortium will be “coordinating” efforts with the TNRCC, but there is no formal coordination mechanism in place to steer that tango.

Hall also says he plans to work with the Texas Air Research Center, a consortium of public universities with an interesting pedigree of its own. The Center boasts an advisory board including a Mr. Robert Nolan of ExxonMobil (a member of the Business Coalition for Clean Air Steering Committee), and a Ms. Pam Giblin, of Baker & Botts, whose past work includes representing the Coalition in its suit against TNRCC. The Texas Air Research Center has lately been contracted by Orange County, which is also struggling with ozone issues, to do its own modeling and research project. (Orange County is paying for its study, not coincidentally, with its own $376,197 slice of coastal impact funds.)

“You want,” Jim Blackburn suggests, “to find out if anybody involved in the litigation is involved in the work for the coastal impact money. If they’re smart, they’ll keep them separate. But sometimes they get sloppy.”

GHASP’s John Wilson thinks he knows how it came to this. “My understanding from the Partnership, not from anybody else, is TNRCC was struggling with this list of projects that they wanted funded, and said ‘Can you help us get money,’ and this is what the Partnership came up with as a scheme to get money. But that also the Partnership’s attitude was, ‘If we’re going to help you get money, we want it not under the control of TNRCC, because we don’t think you guys manage your money that well.'”

But Wilson also thinks that in buying a seat at the table, the Partnership may have bitten off more than it can chew. According to this theory, the oversight mechanisms necessitated by the use of federal moneys may actually give the Partnership less direct control than it’s accustomed to wielding.

“I think because there is a rigorous scientific process going on right now, and there’s a lot of scientists from a lot of different institutions involved, it’s very hard for [the Partnership] to maintain control over the scientific process as they have in the past, when it was just within TNRCC, and they could basically intimidate TNRCC into keeping anything that wasn’t favorable to their point of view under wraps.”

Wilson cites a 2000 study in which several national laboratories conducted flyover surveys of industrial emission sources along the Houston Ship Channel. Tentative data from those flyovers suggests that far from being over-factored, Houston’s industrial emissions may in fact be drastically under-reported as a source of smog-inducing pollutants.

“If TNRCC had found out about it through their own research, the Business Coalition for Clean Air would have probably threatened litigation over it if they came out in public with it [before] it was scientifically validated and all kinds of crap,” Wilson says. “They can’t do that now because the genie’s out of the bottle, it was done by independent researchers at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Admin-istration and Brookhaven and all these places, and these people have international reputations as credible scientists, and they have funding sources that have got some degree of assurance and insulation from the Partnership’s political influence. So these guys aren’t afraid.”

In Jim Blackburn’s view, the flyovers provide more evidence that the Partnership is talking out of both sides of its mouth. If the emissions had been properly reported, the computer modeling, which relies in part on industry-provided information, arguably could have been much better, he says. “And industry on the one hand is complaining about the computer models being erroneous, and on the other hand, there is information that they provided which frankly is at the root cause of some of the modeling problems. And I think, more than that, that they’re misleading the public. They’re not being at all honest about their role in the problem.”

Meanwhile, it’s not just the Partnership that thinks Houston’s clean air plan is badly formulated. On the other side of the fence, a coalition of environmental groups, including Blackburn’s Galveston Bay Conservation and Preservation Association, Wilson’s GHASP, the Sierra Club, Environmental Defense, and the Natural Resources Defense Council, have filed suit against the EPA for approving the Texas plan in the first place. While the Partnership looks to create loopholes through which it can save itself $9.15 billion in compliance costs, the enviros charge that the plan as it stands now is too weak to clean the air.

So who else gets hurt? “If you figure four million dollars,” Blackburn says, “that could have been divided up between ten or fifteen groups up and down the coast and done a lot of very good environmental protection work, instead of funding industry to go study their air pollution problem, which they’ve got absolute ability to fund themselves. It’s not like four million went to a charity. They may be a 501(c)6, but they’ve got the ability to raise huge amounts of money. And they went and got coastal impact money to support basically saving money for industry.”

And yet there exists only one formal complaint on record about the idea that the Greater Houston Partnership should get federal coastal impact funding to conduct self-serving studies of a clean air problem in which it has an enormous financial interest, and that comes from Brandt Mannchen with the Houston Sierra Club.

During the Land Office’s public comment period on the CIAP grants, Mannchen recorded his lonely opposition amidst the 20-plus pro-grant comments flooding in from various chambers of commerce and business coalitions.

“The [Partnership] has a built-in conflict of interest,” Mannchen wrote, “since the large industries it represents have fought the State Implementation Plan and air emission controls that the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission has proposed to clean up ozone air pollution in the Houston-Galveston area. The industries that the Greater Houston Partnership represent pollute the air with thousands of tons/day of toxic air pollutants, nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds. An offshoot of the Greater Houston Partnership, the Business Coalition for Clean Air, has sued the TNRCC over the State Implemen-tation Plan. We do not want the fox guarding the henhouse. If the Greater Houston Partnership gets the grant then the public will be subsidizing industries that are fighting to continue polluting public air.”

The comment, obviously, was not acted upon.

And maybe the Partnership consensus is right, that the coastal booty will be well used to smarten the science to hasten efficient regulation to clean the air to come into federal compliance.

And maybe Wilson’s suspicion is correct, that the Partnership has got its back against the wall, and will no longer be able to exert the control that it would wish over scientific developments that appear to be spiraling beyond its influence.

Hard to tell, this early in the game.

Only one thing, from this vantage, seems certain: That in 2004, at the moment of the mid-course review of the State Implementation Plan, the Partnership’s research consortium will present, as promised, scientific evidence supporting revised regulations that “will reduce the economic burden to the region by $9.15 billion.”

Maybe that science will be solid. That’s the trouble with letting the fox guard the henhouse: You’ve got to trust the fox.

Brad Tyer is a freelance writer living in Houston.