Dateline Texas

Reese's Pieces

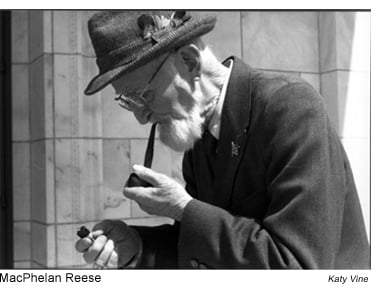

On March 27 at 2:00 a.m., the morning of his 96th birthday, MacPhelan Reese woke up in a panic. He had to find his spiral notebook to write something down, but he remembered that he had hidden it in the kitchen, hoping that he wouldn’t be tempted to fetch it. This new poem, though, was just too good to risk losing: He’s just a flake of dandruff/ That somehow got ahead. He laughed to himself. But a few seconds later he realized that he had already published this rhyme in one of his books, so, only a little disappointed, he put down the notebook and staggered back to bed, confident that some poem would hit him later that morning.

Reese, or “Mac” as his friends call him, is neither well known nor critically acclaimed. His two poetry books–Showdown and Other Poems in 1985, and Gullible’s Travails in 1993–include philosophical, rhyming sorts of poems that have been out of fashion for some time.

“Epitaph to a Schizophrene”

Under this headstone, ‘neath this tree, Here lies buried each of me.

“Brevity”

If ‘brevity is the soul of wit’ Read this quickly and laugh at it: Seduced; She douched.

He might be at very least the Ogden Nash of his city, but not all his poems end with a bah-da-bump. “Epilogue to Sequela,” for instance, ends:

Creed of greed and hedge of pledge Brought me to this window ledge, Five floors up in a cheap hotel to launch my final trip to hell.

The people of Bonham, where he resides, call him both “poet-in-residence” and “Bonham poet laureate.” Because he is modest, Reese doesn’t think either term fits. He once told a newspaperman that his legacy would be the “pie-eyed piper of Bonhamlin.” Some townspeople hope that one day he will be “discovered,” thinking this will make his work more legitimate to the world beyond the city limits, but Reese is too busy to think about such things.

By 8:00 a.m. on his birthday Reese was back on his feet. After drinking a cup of coffee, he slipped on a jazzy green tie and a grey suit, combed his yellow, tobacco-stained beard, and set out for the basement of the Sam Rayburn Library in Bonham, where he has been entertaining visitors with informal chats five days a week since 1975. Since he has a tendency to walk in the middle of the streets, friends and neighbors often stop their cars and offer him rides. He refuses, annoyed. Don’t they know he is working on his deep breathing exercises?

Once he had settled in for the day in the library basement, he shuffled over to the record player to put on a Chopin album, only to find that his first visitor had arrived, causing him to head back to his regular seat, a chair at the end of his long wood worktable, surrounded by bookshelves stuffed floor-to-ceiling with Freud collections, magazine anthologies and history books.

The visitor asked him questions. What was it like growing up in Bonham? Is it true that he became a good fist-fighter to defend himself against taunts that he was frail and cross-eyed? Reese didn’t want to discuss these things, nor did he want to address his job as a gag writer for Burt Levy; his short career as a welterweight boxer that left him with a permanently bent beak; his Midwestern-touring vaudeville act; his time at the Cincinnati music conservatory; or his reasons for moving to Phoenix, Arizona, to “dry out.” He divulged that he came back to Bonham in 1976 because his mother wanted him to come back home, and shortly thereafter he set up shop in the basement and ended up on the payroll. At this, he sucked in his cheeks and rolled his eyes toward the ceiling to make the visitor laugh.

Mostly, Reese wanted to talk about word play. “These poems just come to me,” he says. “Sometimes I say, ‘Please! Leave me alone!’ but it does no good, so I keep a notebook handy and write every thought down. If I didn’t have a notebook I’d be a mess.”

He rarely writes a second draft of a poem and he carries a small notebook in his shirt pocket so that he can jot down his ideas anytime, anywhere. Hundreds of these notebooks have been filled in his home and stacked in a filing cabinet in the library basement. With a shaky hand, he fingers the photocopies of his poems that are spread out on the table in front of him. He reads one aloud, then looks up and asks, “Do you have this one already?”

“Gentleman?”

Impulses controlled, with condoned etiquette He calls each opponent a ‘horse’s rosette.’

“Epitaph to a ‘Hubby’ Hobbyist”

Asleep, alone, at last, Here lies widow Morgan; She chased each husband into church And grabbed him by the organ.

“The Truth Sleuth” Left so uptight by each paradox, His raised eyebrows could pull up his sox.

“See? They just come to me,” he repeated, striking himself on the forehead.

“Have you ever had writer’s block?” the visitor asked.

“Writer’s what, honey?” Reese asked.

“Writer’s block,” the visitor repeated.

“Wri–what? I don’t know what you’re saying.”

“When you can’t think of something to write. Has that ever happened to you?”

Reese seemed stunned by the proposition. “No. I can always think of something to write, even if it’s about not being able to write.”

Impressed, the visitor asked him if he could come up with a poem on the spot. He stared contemplatively at a stretch of floor tile for about 30 seconds, then looked up and said, “Take this down: Necessarily undressed… is seldom caressed.” As if to say, “there it came,” he bugged out his eyes, sucked in his cheeks, and leaned back in his chair.

In the early afternoon, Reese was brought up into the Congressional Record stacks of the library, where his old friends had convened in his honor. This being a Rayburn-proud community, the majority of the company consisted of old Fannin County Democrats. The host–the lanky and energetic H.G. Dulaney, who had worked for Rayburn during the speaker’s last ten 10 years in Washington, had gathered the press, neighbors, friends, local ex-politicians, Dulaney’s co-author of Rayburn books, and a man who had worked as a runner for Rayburn during World War II, among others. Reese greeted each one with comments such as, “What do you say, there,” and “Hello, Queen Elizabeth.” Some visitors–like the man wearing a baseball hat backwards, emblazoned with “OSAN Korea”– received a salute. One woman hugged Reese, inspiring him to howl and bark like a dog.

With everybody in place, Dulaney passed out Cherry 7-Up punch and chocolate cake while Reese drew applause by blowing out the candle that had been sculpted into a “96.” Three men from Denton dressed in white wigs and American Revolution attire impressed the crowd with a color guard exchange. “My goodness,” they said to each other when conversation ran out, “The Sons of the American Revolution. How about that?” Reese was overheard whispering to a visitor, “I didn’t really know anybody in the American Revolution.”

For the remainder of the afternoon, while old stories about Rayburn were swapped (as they usually are in the library), Reese diligently distributed photocopies of his poems. One by one, he led his guests to the piles stacked on Dulaney’s desk, saying, “Take these. Take as many as you want. You’ve already got that one? Well take it again. Here.”

“Sketch (I)”

Pity the plight of the baffled buffoon Who laughs too late or laughs too soon; Ration your pity, to pity more, The scrounging Scrooge, the humorless bore Who stints and stunts his misered praise For fear, wage slave, you’ll beg for a raise; Your begging, your pleading meet foregone defeat– He pays you with praise, then demands a receipt. Look at his shoes, and after you’ve seen them, You’ll see a third “heel” midway between them.

“Cornuto’s Enigma”

The dullest of dullards At last may discover His loyal wife Takes Love as her lover, His faithful wife, Provocative, prim, In love with Love– But not with him.

“Provocation”

The love she accepted as a girl, as a woman she now incites With a diamond’s fire and the glow of a pearl In her taunting, half-whispered “goodnights.”

“Untitled”

By whose command, or whose request, I served “Our Way” with zeal and zest That porcine gods, at last impressed, Might one day grunt, “Come be our jest.”

After Reese fulfilled book-signing requests and the crowd thinned out, a visitor asked if he would be spending the rest of the day with his family. Reese looked up from a mound of birthday cards and replied, “No, I’ve got to get home and do some writing.”

“Really?” the visitor asked.

“Yes. I’m working on a new book. A book of gag poems.”

“What are you going to call it?”

“Sweat Cetera.” He began to giggle to himself.

“Is it coming out soon?” the visitor asked.

Reese paused and raised his eyebrows. Then in a high, sing-song voice he replied, “If I’m lucky.”

Katy Vine is a writer at Texas Monthly.