Dateline Texas

The Business of Corrections

Ingenious. A security fence that not only detects and electrocutes anyone unlucky enough to touch it, but also contains breakaway segments that make climbing impossible. A few booths over, a man politely asks that a reporter not photograph his display of defused stun, stinger and gas grenades, for fear that her article might be distributed in prison. “We don’t want inmates to say ‘Oh, here comes one of those,'” he confides. Less secretive are the two cheery men who convert recycled shipping containers into temporary jail cells. They also build housing for oilrigs, one of them helpfully explains. It’s all part of the exhibition at the American Correctional Association’s winter Conference on Corrections, the industry’s biggest trade show, held this year at the Henry B. Gonzalez Center in downtown San Antonio in mid-January.

In addition to prison and jail administrators, the ACA draws its membership from rehab and treatment facilities, boot camps, Immigration and Naturalization Service detention centers, and community supervision programs, as well as attorneys, judges, and prisoner advocates. Founded in the late 1800s by a group of reform-minded prison wardens, the ACA presents itself as a forum for its members to discuss the current issues in the field. The association publishes a magazine, Corrections Today, with themed issues focusing on juvenile offenders, women in prison, community corrections and more. In addition, the ACA develops standards for and adopts positions on prison-related legislation and legal questions.

Prisoner advocates, however, charge that the ACA is not a wholly benign entity. In recent years, says Meredith Rountree, head of the ACLU’s Prison/ Jail Accountability Project, the ACA has been increasingly dominated by one particular sector of its membership–private, for-profit companies that contract with prisons, or in some cases even operate prisons themselves. These companies, which include household names like Pillsbury and Southwestern Bell, contribute millions of dollars in fees and tax-deductible donations to the ACA. They view the association as a way to wedge themselves into new markets and improve their bottom line. It’s a symptom, advocates say, of the nation’s heavy investment in prison construction over the last two decades, and the seemingly permanent increase in spending that comes with keeping those new units filled. Across the country, legislators have made corrections the new public trough, and the usual suspects are lining up to feed.

Although the schedule lists a track of unspecified business meetings, insiders say the actual policy work of the association happens at the ACA’s summer conference. The winter get-together is mostly a trade show, a chance for members to get out of the snow and talk shop on the company dollar. As trade shows go, this is one of the weirder ones, especially for those unfamiliar with the culture of corrections. The keynote speaker on Monday was Lt. Col. Oliver North, who warmed up the crowd of prison officials and contractors with a few jokes at his own expense. “I was almost one of your guests,” he cracked, before delivering a speech on, of all things, military recruitment. North, who has no experience in corrections, has become a mainstay of the right-wing talk radio circuit. He received a standing ovation for his call for universal mandatory conscription.

Back downstairs, a two-man marching band played “Go Tell It On The Mountain” and “Semper Fi” as exhibitors handed out trademarked shoulder bags, keychains, and other gimmicks. DuPont handed out eyeglass straps made of bulletproof Kevlar to promote their corrections-grade body armor. The mood among the purveyors at the dozens of booths and displays was optimistic. And why not? From 1980 to 2002, harsh sentencing laws, particularly for drug crimes, and reduced parole rates have caused the incarcerated population of the United States to quadruple to over two million, the highest per capita rate of any country at any time in history. Keeping those facilities supplied with everything from toothpaste to Tasers has become a $40 billion annual industry.

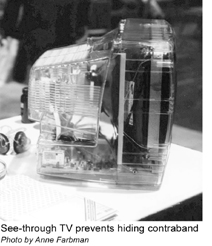

“Think of a prison as a city,” said Wayne Barte of the Office of Law Enforcement Technology Commer-cialization (OLETC), a federal agency that also rents a booth at the convention. “You provide the things people in a city would need–a post office, hospital, dental care, police, a fire department,” he said. “You need to feed, clothe, and do laundry.” At the convention, corrections officials can order “floss loops,” dental aides that can’t be used–as dental floss can–as an impromptu cable saw, as well as short, softened toothbrushes that can’t be fused with razor blades to make deadly shanks. One trend apparent at the exhibition is making consumer goods–everything from televisions to toothpaste tubes–transparent, to prevent hiding contraband.

The other obvious trend is high technology. The future of surveillance and control–the two imperatives of correctional technology–is not towers and shotguns. On display here are iris scanners, mail scanners, laser proximity scanners. Wayne Barte’s agency, the OLETC, shepherds police and correctional technology from the development phase through manufacture and marketing, working with a variety of companies, ranging from old-school defense contractors like Raytheon to start-ups, like Arritech drug-testing. OLETC also sponsors the famed Mock Prison Riot, an annual showcase held at the former West Virginia State Penitentiary. At the demonstration, manufacturers and riot response teams can try out new techniques and equipment in staged “disturbances.” The prisoners, played by police and correctional academy students, suit up in training armor and enact plausible scenarios, which the trainee teams attempt to control with everything from remote-control smokescreen dispensers to refrigerator-sized portable cells.

The high-tech turn disturbs some in the reform community, who worry about civilian applications of the new devices. Frequently, activists speak of a “Prison Industrial Complex,” an “increasingly symbiotic relationship between private corporations and the prison industry” as one California-based group defines it. Nervously, they watch the social effects of this relationship–from the adaptation of correctional models to social programs, to the crossover in technology. “The military gave us reasons to develop certain types of technology that found their way into everyday use,” explains Tamara Serwer, a prison advocacy lawyer with the Georgia-based Southern Center for Human Rights, who spoke at a “counter-conference” sponsored by a coalition of ACA critics and prison reform groups. Some have been beneficial, like the Internet; others, like nuclear power, have been a nightmare. “[Prisons] need to know everything around them–identities, locks, every door and bed,” Serwer says. “What’s the normalized use going to be for us?”

Serwer is not the only observer worried about the spillover of corrections technology into the free world. In May of 2000, the Department of Justice released an alarming essay by Dr. Tony Fabelo, director of the Texas Criminal Justice Policy Council, entitled “Technocorrections”: The Promises, the Uncertain Threats. Fabelo saw “technocorrections,” defined as “the potential offered by the new technologies to reduce the costs of supervising criminal offenders and minimize the risk they pose to society,” as a force capable of changing the nature of correctional philosophy–and a potential threat to democracy as well. Many of the developing technologies Fabelo surveyed were aimed at identifying, monitoring, and pharmacologically treating individuals outside of prison. Fabelo praised the technology’s potential to ease the load on the prison system by allowing more offenders to be released than with traditional supervision. On the other hand, the availability of these technologies, he argued, could lead to them being used outside of a correctional context–i.e. before the individual even becomes an offender–and without the current guarantees of due process.

Some of Fabelo’s hypothesized inventions–satellite/cellular tracking systems that incorporate “safe zones” subjects must avoid, like ex-partner’s houses, technological assessments of an individual’s likelihood to molest children, and genetic screening for predisposition to violence–are already available and on display in the ACA’s exhibit hall. Fabelo was particularly concerned about the prospect of “preventive incarceration,” in which certain suspect groups “could be placed under closer surveillance or declared a danger to themselves and society and be civilly committed to special facilities for indeterminate periods.” This is not far-fetched–12 states allow preventive incarceration of child molesters after they have served their full sentences.

There are technological nightmares inside prisons as well. At a packed workshop on riot control technology, a warden from California complained that it is impossible to get replacement parts for his new pepper-spray/water-cannon system. Chemical weapons like pepper spray–which causes horrible, albeit temporary, burning of the skin and eyes–are becoming increasingly popular in prisons. Advocates worry that because the weapons are non-lethal and relatively economical, officers tend to use them too frequently and without just cause.

A bit later, Rodney Cooper, the presenter of the workshop and a former warden of the Walls Unit in Huntsville, casually explained why Texas prisons do not use stun shields, riot shields equipped with Taser-like electric shockers. As part of training, he said, officers authorized to use the shields had to first test them on themselves. The program was scrapped when a cadet died of a heart attack. Still, sales of such “less lethal” devices have been brisk throughout the nation.

Incarceration as an industry is relatively recession-proof. Yet certain segments have had their setbacks in recent years, particularly private prisons. Local and state governments (and eventually the feds) jumped on the privatization bandwagon in the 1990s; until last year there were 158 private correctional facilities in the United States, with Texas leading the pack at 43. The last few years, however, have dealt a number of blows, from which the still-nascent industry seems unlikely to recover. In 1996, the U.S. General Accounting Office released a report blasting the savings forecasts of privatization. Far from the promised 20 percent savings over public facilities, the GAO concluded that private prisons save governments 1 percent at most, and in some cases actually cost more than comparable public facilities. In February of 2001, the U.S. Department of Justice reported that when private rates were lower than public, the savings came out of workers’ wages and benefits, and often resulted simply from non-union contracts.

In addition, private prisons have been rocked by a series of scandals, notably in Youngstown, Ohio, and Jena, Louisiana, where charges of abuse and mismanagement have led to facilities being closed or returned to state operation. Nationwide, private facilities have been struggling to fill capacity, often importing prisoners from other states. In 2000, Corrections Corporation of America came within a hair’s breadth of declaring bankruptcy, and continues to operate in the red with 12,000 empty beds system-wide. New private prison contracts have virtually dried up. In September of 2000, Business Week concluded “the industry’s heyday may already be history.” But don’t cry for them yet. At least one major private prison operator, Wackenhut Corporation, has seen its stock price jump in the aftermath of September 11. Companies across America are spending money on heightened workplace security, a niche in which Wackenhut is also a major player. Meanwhile, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, traditionally a big customer of private prisons and jails, has arrested thousands of people in connection with the federal investigation into the attacks, providing a quick infusion of cash into the industry. How temporary that windfall will be remains to be seen.

Here in Texas, there are hints of a slowdown in the prison boom. Legislators last session balked at committing to any major new construction projects. Absent any sentencing reform, however, there will still be plenty of money to be made in Texas prisons. As critics of the U.S. military have warned for years, institutions, even peculiar ones, have a way of perpetuating themselves. Walking among the booths and the bustling sales reps at the convention center, it’s hard to imagine this one disappearing anytime soon.

Anne Farbman is a freelance writer living in Austin.