Small Mercies

A Review of "Kathy Vargas: Photographs, 1971-2000"

Kathy Vargas: Photographs, 1971-2000

Kathy Vargas still lives in the house where she grew up, in a predominantly African-American and Latino neigh-borhood in east central San Antonio. Ever since she took her first “serious” photograph, she has been documenting the lives of the people of San Antonio and, more immediately, her friends and family. That first picture, shot in 1971, showed the blurred, shadowed face of a local woman who had suffered a stroke. Though her work has subsequently evolved through many stages, the presence of illness and death has remained an abiding theme in all of Vargas’s photographs. Through hand-coloring, collage, and writing text on top of her images, she adds a haunting individual touch to the multiple medium of black-and-white gelatin silver prints.

Vargas has been exhibiting steadily for the past 20 years, and her photographs are becoming increasingly well-known. Her work has been shown throughout Texas, as well as in Italy and Germany. Last year she earned her own retrospective at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio. Those who missed that exhibition, or who want to share her work with people who don’t know it, can use a nicely produced and reasonably priced catalog, Kathy Vargas: Photographs, 1971-2000, which comes with an introduction by MaLin Wilson-Powell, curator at the McNay, and a chatty but informative essay by Lucy Lippard, an eminent art writer and a longtime friend of Vargas’s.

Before Vargas became a fine art photographer, she took commercial pictures of rock’n’roll musicians. From this period in her career, according to Wilson’s introduction, she retains a loss of hearing in her left ear (from standing close to concert speakers) and an abiding love of pop music, whose lyrics and sensibility (especially those of Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan) inform her work. For a brief time she was a member of Con Safo, an organization of Chicano artists who were promoting political art and trying to move their work into the mainstream in the late sixties and early seventies. Though Vargas sympathized with the group’s politics, her own work agenda was more implicit than overt, and she left the group after less than a year.

But you don’t have to look too closely to see the political subtext (or, in the case of handwritten additions, super-text) of her pictures. “Racism, feminism, AIDS, and censorship are the issues that have driven her,” Lucy Lippard observes. “Yet even as she acknowledges suffering and would love to change the world, Vargas’s political sophistication, her sense of humor, and a certain wisdom combine in a serene acceptance of the way lives play themselves out, perhaps inherited from her Zapotec and Huichol ancestors. Which is not to say that she is free from anger at injustice.”

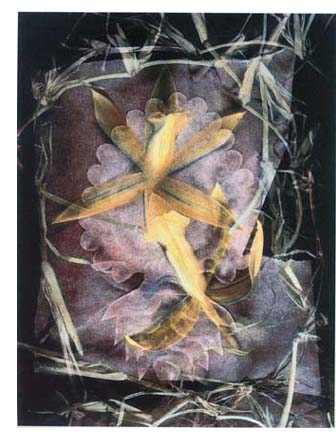

In the early 1980s, Vargas completed a series of pictures of local household shrines: the altars, pictures of the Virgin Mary, and the flowers and gifts to her found in many yards. The emotional focus of the shrine–its nexus of prayers and sadness, what curator Roy Flukinger has called “the hard truths, small mercies, and ever-arising hopes of this journey”–is one she has continued to play with since then. Her series of “seafood saints” (the fish that died to feed her, and give her life) show crawfish and squid in dreamy assemblages, colored in pale, angelic pastels. Later, in installations, she added to her photographs three-dimensional items like flowers and skeletons.

After working for some time as a fine artist, Vargas eventually went back to school, earning both her BFA and MFA from the University of Texas at San Antonio. For 15 years, from 1985 to 2000, she was the Visual Arts Program Director at the Guadalupe Cultural Center. She coordinated the annual Hecho a Mano show and assiduously promoted the work of local artists.

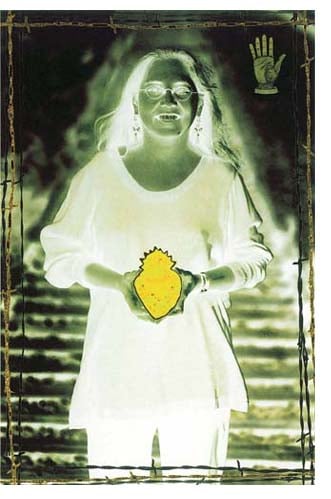

At the same as she held this position, Vargas kept taking pictures, and her work continued to develop. Crucial aspects of this work are the importance of family and the inevitable spectre of death. Vargas took care of both her mother and her grandmother until they died. In 1997, after her mother’s death, she mounted an installation at ArtPace, the contemporary art foundation in San Antonio. Entitled State of Grace: Angels for the Living/Prayers for the Dead, the installation was a ghostly three-dimensional portrait of loss. Glowing figures surrounded by wings, thorns, and other imagery testified to the continuing presence of the dead in our lives.

Like Joel-Peter Witkin, the Albu-querque photographer whose morbid black-and-white pictures of death masks and other paraphernalia are off-putting to many people, Vargas is intensely preoccupied by death. Yet her photographs have a completely different cast than his, because she isn’t interested in the grotesque. Some of her images, in fact, are coated in a veneer of prettiness–a flowery, greeting-card aesthetic–that can feel lightweight. At their most successful, though, her pictures confront death without sentimentalizing it.

In a letter to Lippard, quoted in the catalog, Vargas describes a visit to the archaeological site at Palenque, in southeastern Mexico, and contrasts the Mayan view of death–open and accepting–to our own culture’s denial of it. “Everyone here refused to look at it,” she writes, “wants it clean and sterile and removed, something that isn’t real. I want to shake them and say ‘look at it; it’s a great offense to humanity; stop killing.'” In series like her Valentine’s Day/Day of the Dead pairing, she joins together a skeleton, hearts, and flowers in a deceptively serene image that offers tribute to two friends who died of AIDS. Of their deaths Vargas says matter-of-factly, “We all prayed for a miracle to save their lives, but it never came.”

In the early nineties Vargas was invited to participate in a group exhibition called Hospice, organized by the Corcoran Gallery in D.C., along with the noted photographers Jim Goldberg, Nan Goldin, Sally and Jack Radcliffe. “Typically,” writes Lippard, “she decided to concentrate not on the ravages of the illness, but on positive aspects of patients’ lives and deaths, with lace and flowers veiling but not denying the harshness and pain.” These photographs are among the highlights of the book. “Hospice: Don and Bill (Bill)” is a collage. In the lower left-hand section is a portrait of a man with a moustache, shirtless, leaning back on a chair on his porch, on what looks to be a hot Texas day. On the right side, looming in shadow behind him, is a copy of his death certificate. The conjunction evokes an ordinary and terrible sense of grief.

In other photographs Vargas has allowed her political consciousness to speak more directly. For example, she tackled the Alamo, and her own complex feelings toward that monument, in a series of pictures from 1995. “Living all my life in San Antonio, Texas, and being both Chicana and Tejana, I have negotiated that relationship for what seems like an incredibly long time,” she writes. Commenting on the series, which offers up guns and stars together with tableaux of her own ancestors and other figures, she refers to “the racism that is part and parcel of standing before war monuments and thinking oneself to be on one side or another, either by choice or because history gives us no choice.” Her great-great-grandfather, Juan Vargas, was an indigeno who was recruited on the Mexican side in the battle; because he could not be fully trusted, he was armed with a broom instead of a gun. Vargas’s portrait shows him in white, sweeping delicately around the edges of the Alamo.

Although the Alamo series is more explicitly political than others, it shares with the rest of Vargas’s work the common thread of looking at the past, and dealing with the emotional aftermath of what came before. Like many contemporary artists, Vargas seems intent on expanding the boundaries of photography by working with collage and by altering photographs both manually and technically. What’s nice about her work is that despite all the alterations, her photographs maintain their personal feeling; they are meant to act as mementos, as something to remember loved ones by.

Seeing these photographs in a book is different from seeing them in a museum. Reproduced on small white pages they lose some of their ghostly charisma, especially the three-dimensional impact of an installation environment like ArtPace. What they keep, though, is their photo-album sense of intimacy; looking at them is like flipping through the collective memory of a family you think you once knew. That sense of cherished connection makes each photograph into a shrine; as Vargas says of her silver gelatin prints, “the loved body is immortalized by the mediation of a precious metal, silver.”

Alix Ohlin is a graduate of UT’s Michener Center for Writers.