Apparent Illusions

In a world filled with uncertainty–and when has it ever been otherwise?–there is one thing of which you can be sure: You can never have enough books. So one Saturday afternoon soon after I moved to Austin I went trolling for answers in the history and travel sections of a second-hand bookstore, where I found myself staring at two stacks of books slumped against a bin.

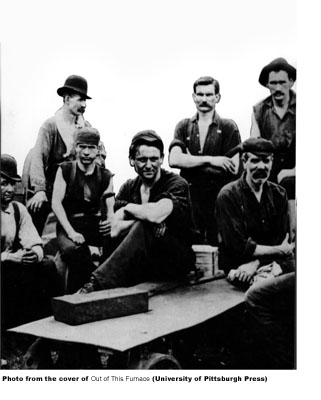

They were worn, discarded copies of Out of This Furnace, a three-generation family saga about immigrants from Eastern Europe and the steel mill towns outside Pittsburgh. The novel by Thomas Bell begins with George Kracha, a hapless young man who in the 1880s leaves his home in the easternmost corner of the Austro-Hungarian empire. He arrives penniless in New York, having frittered away his meager savings in an unsuccessful attempt to seduce an attractive dark-haired, dark-eyed young married woman on the boat to the United States, and walks from Manhattan to the rail yards of Pennsylvania, where a job awaits him. The next generation tries to do the right thing–Kracha’s daughter marries a man who is so earnest, so hardworking that his name, Dobrejcak means “good man.” But they are plagued by the bad luck that comes from back-breaking work in the mills and ghastly industrial accidents. Because the author was something of an optimist, as well as a champion of labor rights, the third generation is the story of a triumphant unionization campaign, along with all the ambiguities that come from acculturation. As he slyly observes in an author’s note, Out of This Furnace was a thinly disguised version of his family’s own history: “This book is a novel, fiction, and–allowing for the obvious exceptions–the proper names used in it do not refer to actual persons who may bear the same or similar names. With that said, this much more may be: I have been as true to the events, the people and the place as lay within my power.”

When it was first published in 1941, it was heralded as a novel of “the new immigration,” or as one critic described it, a portrait of “the America of the newcomer for those who sometimes forget that at one time they too were newcomers.” But by 1950 it was out of print and might have faded away forever had it not been rescued many years later by a professor of English at Carnegie Mellon University. Dave Demarest tracked down Bell’s survivors and wrote an Afterword for a new edition, which was published in 1976. Since then it has sold more than 150,000 copies. The novel was once listed among the top 10 fictional works published by university presses (Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Eugene O’Neill’s family saga, was ranked number one.) It appears on countless reading lists in universities throughout the country; a professor of urban geography at the University of Liverpool not only teaches the book, twice he has brought his students to walk through deserted industrial landscapes and stand at the grave of a man named Mike Belejcak, the father of Thomas Bell and the model for the fictional Mike Dobrejcak. And that’s where things start to get interesting–at least as far as I’m concerned.

I have seen photographs of Nizny Tvarozec, the village where my grandfather was born. In 1978 one of my uncles traveled to what was then Czechoslovakia and came back with a stack of remarkable documents, the kind of photographs you do not see anymore, where everyone stands perfectly straight and stares into the camera because having a picture taken is a special occasion. There is the great-uncle with the hat and cane and Zapata mustache, who once snuck into Canada to visit family in the United States. He bought a nickel candy for my father and his siblings, then slipped away. He didn’t like it here and spent the rest of his days drinking rum and making elegant wood carvings back home. There is the cousin who went away to Kamchatka for several years. No one knows why, but nevertheless he returned to his village as A Very Important Person. There is the hillside–so beautiful and peaceful–where another cousin was killed when he stepped on a landmine. There are the gypsies whom everyone is taught to fear and loathe (while ignoring the obvious–the dark hair, dark eyes that pop up every now and then in family photos, as well as the gypsy inclinations to take off whenever we please).

But I had never heard of Thomas Bell–or Belejcak (the way our name is supposed to be spelled, according to my uncle). Then a few years ago a message appeared on the computer screen from a woman in California. “I don’t mean to be presumptuous,” she began, “but I think we are related.”We certainly were. Our grandfathers were brothers, who had emigrated as teenagers from the same Eastern European province where Bell’s father was born. In their old age they had argued bitterly–two old men sitting on a bench, lost in the twilight world between the Old Country they had left so long ago and the New Country they never really understood and which never really understood them. They argued about the existence of God–one was a believer, the other was not–and then never saw each other again.

My newly discovered cousin and I began to write. It turned out that we had been born in the same town a month apart and were now living thousands of miles away, she in California and I in Mexico City. She had once visited the house where my grandparents used to live, where my parents now live. As I read her description of a visit that had taken place more than 30 years before, I began to think that there was a parallel “me” out there somewhere in cyberspace. Now she was working on a family genealogy and that’s how she discovered Bell’s novel. I bought a copy and sent it to my father, who read it in a day, amazed that someone could write a book in English and sprinkle it with words that he grew up on. He began calling it the book about our family. But is it? There are differences both major and minor in Bell’s story and our own. I like to think that the village of Nizny Tvarozec is what I have long imagined it to be–a village like so many I have visited all over Latin America, where everyone is named Pérez or López.

So there was something disconcerting about finding all those copies of Out of This Furnace in a used book store in Austin. When I saw those two stacks of books with the “used” sticker branded on their spine, I couldn’t help wondering. Who had assigned the novel and who had read it? Who were they? And what had they thought about this book that is and is not the story of my family? Suddenly I wanted to buy all those books and take them home. I didn’t of course. But I would have saved them if I could.