Picturing Afghanistan

On September 11, like many of you, I spent most of the day and most of the night staring at what looked like the end of the world on my television. At one point in the evening, the anchors broke away from replays of the World Trade Center crash and coverage of the rescue efforts in Manhattan to show what seemed to be a missile attack on Kabul, Afghan-istan. The correspondent was standing on a hotel rooftop overlooking the city, reporting on what some thought might be the first U.S. attack in the war. It soon became clear that it was just another sortie in Afghanistan’s lingering civil war. While the reporter was speculating that the Northern Alliance had blown up a Taliban munitions dump, something struck me as odd. The cityscape behind the reporter, flickering as it was through his videophone connection, seemed altogether too modern, too whole. Rows of streetlights illuminated the city’s avenues, and it looked more or less like any other hilly city in the world.

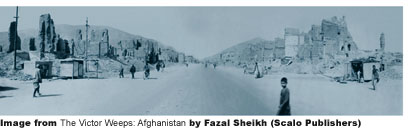

On my bookshelf, I had a copy of Fazal Sheikh’s The Victor Weeps (Scalo, 1998). I flipped through the pages of the book quickly and found images of Kabul that confirmed my suspicion. In the daylight, Kabul doesn’t look anything like a city. It’s a bombed-out, dusty moonscape. The shattered buildings look more like an archaeological dig than a habitable city.

I turned to The Victor Weeps and the other books of photojournalism that I mention in this essay the same way some people turned to scripture or to the American flag. I was looking for answers, for insight, for some sense that the world is intelligible, for reassurance that we can look at life and make some sense of it. I wouldn’t say I found any answers there, but answers are hard to come by lately. In the days after the attack in September, a friend kept asking me what my solution would be for the problem, taking it on faith that there is some solution. In the books that I looked at, it seemed clear to me that the photographers were searching just as hard for answers, or even for a way to ask the right questions, as the rest of us are.

Fazal Sheikh’s grandfather was a Muslim cleric who emigrated to Kenya from what was then India. Sheikh’s family eventually settled in New York. In 1996 Sheikh traveled to his grandfather’s old village in what is now Pakistan. When he arrived he found that the region was home to hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees. Many had been mujahedeen who first helped to dispel the Soviets and then were driven from their homes by the Taliban. Sheikh began to photograph these refugees and to record their stories. Eventually he traveled to Afghanistan to photograph there, too. The Victor Weeps is the result. In gratitude for their help with the book, Sheikh is donating some of the proceeds from the book to aid the refugees.

It would be impossible to tell the story of Afghanistan with just one kind of picture. Sheik uses a variety of techniques. There are the glowing, cratered cityscapes. (They really do have the same extra-bright glow that pictures taken on the Moon by the Apollo astronauts have.) There are sumptuous, chiaroscuro portraits of Afghan refugees living in Pakistan. Some of the men seem lit by a campfire, with dark-clouded faces and a sharp glint in their eyes. There are close-up shots of people’s hands, holding the photo IDs of their dead brothers, husbands, fathers and sons. There is a section of prints that Sheikh made from the scratched and battered negatives of a Jalalabad portrait photographer who was put out of business by the Taliban prohibition on photography. Not all of the pictures are photographs. The book begins with a selection of children’s drawing in the familiar naïve style of grade school kids. Here, instead of a house with a tree and a rainbow, the kids draw portraits of men getting their legs blown off, blood and body parts spurting every which way.

Many of Sheikh’s portraits are accompanied by quotes from the subject or an anecdote that someone else told about them. They tell about things like fleeing from their villages after all of the religious elders were buried alive in the desert by the communists. Sheikh also includes notes about things he saw and people he met, like the children of Kabul who would rather risk getting blown up by gathering firewood in a minefield than be assured of dying from the cold.

There’s a photograph of a sturdy, fierce, “Afghan fighting dog,” taken from what seems like a prudent distance down the street. Sheikh did not keep his distance from the pain and suffering of his human subjects. In the early days of our war with the Taliban, I would look at the hard, determined men in these pictures, and wonder how we could ever hope to defeat them in battle. As I write this in early December, it looks like our military campaign has gone more smoothly than many of us feared, with swift victories and few American or civilian casualties. But something tells me that this story is far from over.

That was the same reaction that photojournalist Edward Grazda had when he traveled to Kabul in 1992 to cover the mujahedeen victory over the Soviets. Grazda has been covering Afghanistan for decades. His book Afghanistan: 1980-1989 covered the years of the Soviet invasion and the beginning of the civil war. He returned to Kabul in 1992 to cover what he thought would be the conclusion of a long struggle, and then watched as the factions that had fought together to oust the Russians turned against themselves.

Over the next eight years, Grazda returned several times to photograph. The pictures that he made on those trips appear in his latest book on the cycle of crises in Afghanistan, Afghanistan Diary: 1992-2000 (PowerHouse, 2000). The war against the invaders devolved into a civil war, and Kabul was transformed from capital city to battleground. Grazda writes that each attempt to reach a peace accord only led to more rockets, more rubble, and more death. From this chaos, the Taliban rose up and drove the Northern Alliance from Kabul. Soon, clean-shaven men, unveiled women and photography were outlawed.

Like Sheikh, Grazda is visibly struggling with the limitations of the form, trying to stretch photography to the impossible task of showing us a country, a civilization, a culture, as it disintegrates. Grazda even goes so far as to include a disclaimer on the title page, writing that the Diary “is one photographer’s view of the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan, and as such is not intended to be a complete picture of the Afghan situation.”

Grazda’s view includes many attempts to capture elusive moments of Afghan history. Grazda shoots before-and-after diptychs showing the effects of the civil war and the Taliban occupation: Buildings crumble, women disappear from offices and from the streets, and all of the faces stop smiling. He shoots multiple views of monuments and stitches them together to form composite images. The pages of the book are crowded with multiple images, frame lines nearly overlapping, images bleeding to the edge of the paper. Where Sheikh’s photos are formal and elegant and vibrating with constrained misery, Grazda’s pictures are kinetically charged, with lots of hip-shot snaps and off-kilter images taken through the window of a car or in the tumult of a crowded street.

Grazda photographed in Kabul and Mazar-I-Sharif. (Could he have imagined that the names of those cities would be heard nightly on American network television?) He photographed in the Afghan communities in Pakistan and in Queens, New York. He introduces each section of photos with a brief essay. (One complaint: The captions for the photographs are in the back of the book, with photos identified by page number. Frustratingly, many of the pages are unnumbered, which can make it hard to figure out what you’re looking at.)

Grazda also includes transcriptions of several Taliban decrees. Some of them seem almost funny–an insufficiently bearded man “shall be arrested and imprisoned until his beard gets bushy”–if we didn’t know that the rules were enforced with impromptu rubber hose beatings (which Grazda photographed) and with torture and summary executions. (The line where the Taliban promised to “continue their efforts until evil is finished” was also disturbing, because it sounds like some of the weirder rhetoric that our own leaders have been using since September.)

Those who would stamp out evil have much to do. There have been huge changes in the way people around the world live in the last half-century. Some of us are doing better than ever, but millions aren’t. Sebastião Salgado’s Migrations (Aperture, 2000) is an attempt to document the details of some of those miserable new lives and offers still another glimpse at the Afghan situation. Salgado made pictures of Afghan refugees in Pakistan, of an orthopedic hospital that makes (or is it made?) prosthetic legs for landmine victims, and of the ruined skyline of Kabul. In the mountains, shepherds herd their flocks past tanks and armored personnel carriers. One of the most startling pictures was of a group of Tajik refugees who had fled their Tajikistan to, of all places, Afghanistan.

So what can these photos show us? Are these displaced peoples with their worlds turned upside down the pieces of a puzzle, with a solution that we can find? Or are they the shards of a shattered glass, broken beyond repair? Last summer, before September 11, I saw a re-run of an old Bill Moyers interview with Joseph Campbell. Campbell was saying that the greatest challenge that we face is to find some unifying mythology that allows us all to recognize each other as human, as part of the same tribe. Looking at these pictures, and at the events of the last several months, one thing is clear. The world is a mess. Only some of it is our fault (as Americans, as consumers, as good men and women who sit by and let evil roll unchecked through the world), but all of it is our problem. The questions that these pictures raise are just the beginning. Let’s hope we can see some answers.

Jake Miller has recently completed a series of children’s books on the history of the civil rights movement.