Afterword

"Your Poem is Happening All Over"

An American neighbor says the most startling detail I ever told her after a trip to the West Bank was that Palestinians weren’t allowed to have their telephone numbers listed in any directory. (It might have been seen as an encouragement to get together.)

Until just a very few years ago, Palestinian artists weren’t allowed to use the colors green or red in their paintings. Those colors were prohibited in work displayed in the few tiny galleries in the West Bank because they are part of the Palestinian flag. “We also aren’t supposed to paint people,” the gallery owners said. “Our paintings might be interpreted as being incendiary by the Israeli authorities.” “Well, what can you paint?”

“Flowers.”

“Without the color green?”

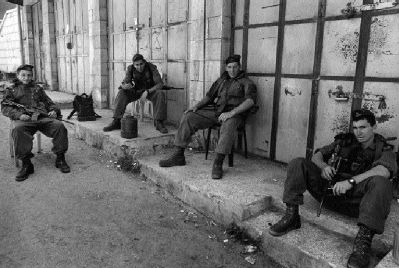

Once I was sitting talking with my grandmother, who was then about 105 years old, when an 11-year-old cousin burst into the room weeping, his face purpled, both eyes rapidly growing black. He lived down the road in the village and had just been assaulted by an Israeli soldier while taking a shower in his own house. The soldier had burst in upon this child in the bathroom and beaten him up, while the boy was naked and wet-and for what? The soldier, who had a huge rifle paid for by my American tax dollars dangling from his shoulder, thought my cousin might know another boy who had thrown a rock at a tank a few days before.

Some years ago I was asked to contribute a poem for an anthology. I had just returned from Jerusalem, where I had tea with a beautiful Palestinian friend from Bethlehem who poured her recent woes out onto the white tablecloth alongside our sugar bowl. My notebook pages were filled with everyone’s painful eyewitness accounts of recent horrors.

The poem I wrote for the anthology was called “Burning.” It described what had recently happened to my friend when she shopped for cheese in a Jewish deli in west Jerusalem. She shopped there because they had a bigger cheese selection than stores in her own neighborhood.

My friend is very glamorous and looks better than most people anywhere, much less someone living in a beleaguered city in an occupied country. While browsing amongst the wheels and slabs and chunks of sharp and very sharp and rare and pungent, she turned her back on her purse in the shopping cart for a moment and the Israeli shopkeeper said to her loudly in English, “Watch it! There’s an animal here.”

She turned. An old Arab man was sweeping the floor. Arabs are often hired by Jews at low wages to do menial jobs. The sweeper looked like my friend’s father and her uncles and her neighbors and all the men she had ever trusted in her life. But her throat filled up, her mouth froze and she could not speak. She could not say, “That’s okay, I’m an animal, too.” She bought the cheese in silence. Took it home and could not eat it. Her throat burned for days. She was mad at herself for buying the cheese and not speaking up.

Well, the anthology published my poem. But the editor, who happens to be Jewish, told me later she didn’t really like it. She didn’t want to believe it. A year or so later, she faxed me from London. She had just spent a month in Jerusalem and was honorable enough to want to clear something up. In essence she said, “I apologize. Your poem is happening everywhere, over and over again. I saw it with my own eyes. I had not been prepared for such cruelty from my people.”

Yehuda Amichai, the beloved Israeli poet who died in the year 2000, said to me in the mid-nineties, “I want you to know that no Arab house ever stood on this spot where my dwelling stands. I could not live here if this house or this land had been taken from another person.” He, his wife and I were finishing an excellent breakfast of scrambled eggs, pita bread and olives at their dining table. He stared out the window toward the Old City of Jerusalem. “I could never live in your father’s old house.”

He knew that my father’s old house had been seized by Israeli commandos in 1948 and my father’s family not allowed to return. I told him Jewish rabbinical students from New York were studying in that house now and he shook his head.

Born in Germany, Amichai came with his parents to Palestine in 1936 when he was 12. He knew what it was like to be a person-in-exile. He and my father witnessed the same dramatic days of 1948 from different perspectives. Later Amichai would write, “My bed/stands on the brink of a deep valley/without rolling down into it…” He was sensitive to other people’s stories as well as his own-a poet’s responsibility.

And he was troubled by many things that he witnessed. His son had been in the Israeli army. He and his wife worried a great deal about all the young people being killed in continuing conflicts. “The moderates on both sides need to have louder voices!” he insisted. “Otherwise we are only hearing the extremists.”

“It has never been the style of moderates to SHOUT,” I countered.

“Of course not,” he said, staring out his window. “But maybe we need to now.”

Amichai is dead and his words ring even louder. How do we shout? Where? To what audience?